By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

Any budget is about two things. How much the government spends and how it raises the money.

In a national budget, most revenue comes through taxes and tariffs. Ahead of budget day, it helps to revisit the basic principles of good taxation, because businesses and households worry not only about new taxes, but also about shifts to thresholds, exemptions, holidays, and border tariffs.

The President has indicated that the new Budget does not plan to impose new taxes, which is welcome. But tax is a technical field. Even without new taxes, changes to rates, bands, and holidays can reshape the burden. All this happens while Sri Lanka is in its 17th International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme with agreed benchmarks.

Govt. spending today is tax tomorrow

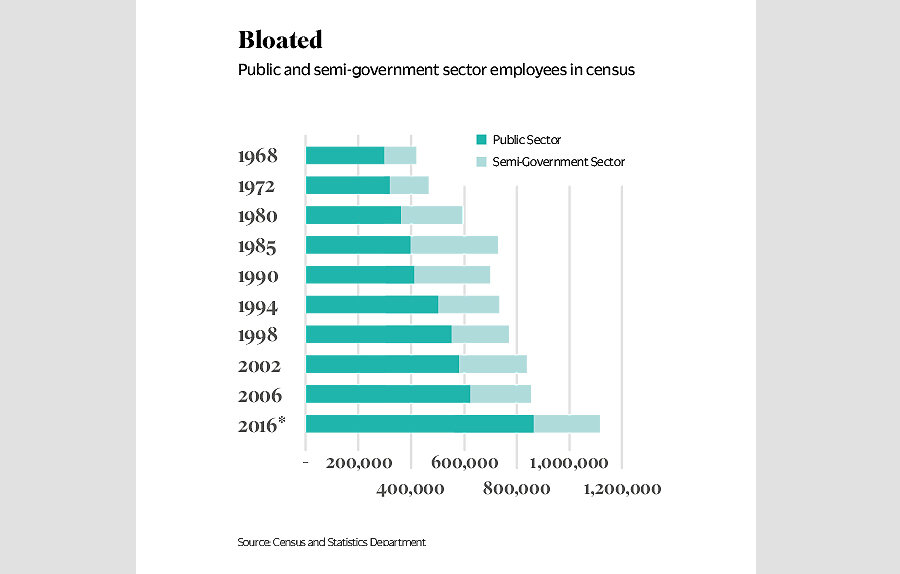

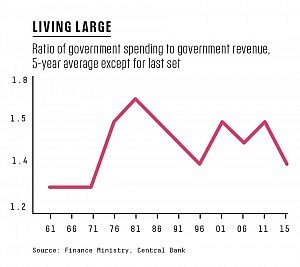

There is a blunt truth about public finance. Every rupee the Government spends must be paid for by someone. If it is not collected this year, it will be collected in the future. When we borrow to fill the deficit, interest and repayments still come from taxpayers.

Unlike a household, a sovereign can also create money. That route does not make costs disappear. It shifts them into inflation, which works like a hidden tax. This is why every expenditure line in a budget is, in effect, a future claim on citizens. Discipline on spending is the foundation for a lighter, fairer tax system.

Taxes at the border are the worst kind

Among ways to raise revenue, tariffs at the border are generally the most damaging. They raise prices for consumers, protect inefficiency, invite lobbying, and complicate trade.

This column has often examined tariff policy, so today the focus is on core tax principles that should guide the Budget.

Simplicity

Tax rules should be simple to understand and simple to administer. Complexity breeds loopholes, evasion, and higher compliance costs. Multiple bands, special cases, and technical fine print frustrate honest payers and overwhelm administrators.

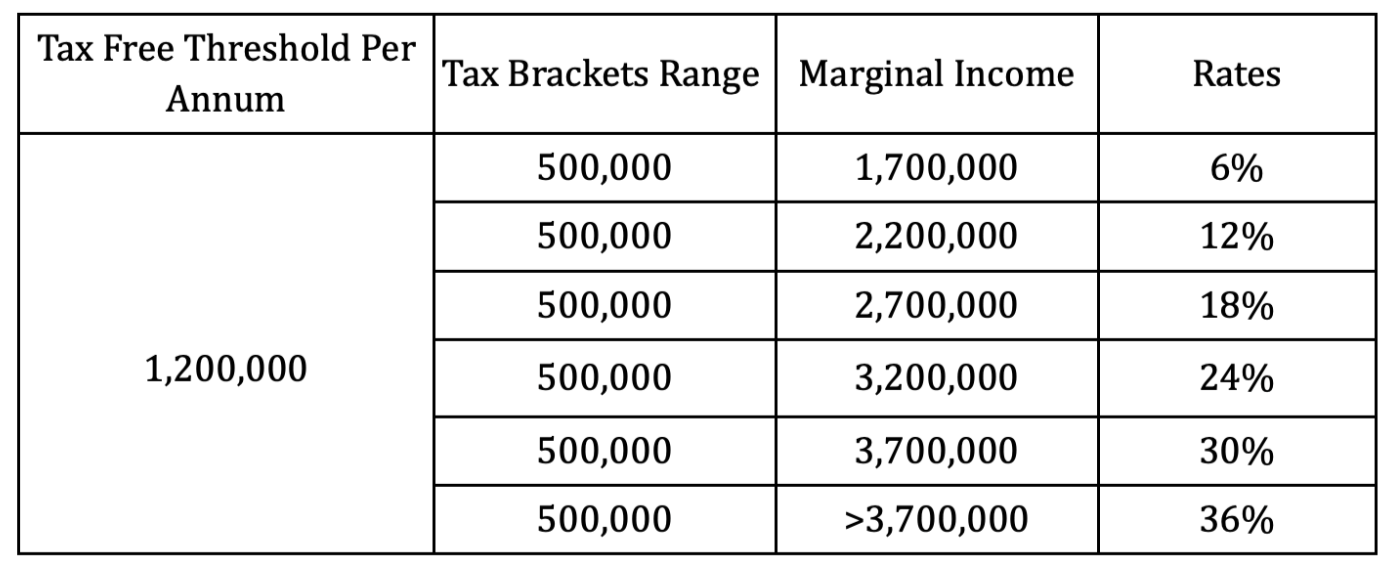

Sri Lanka’s personal income tax already has several thresholds and special treatments, including differences by source and currency. The direction of travel should be towards fewer bands, clearer definitions, and straightforward filing.

Transparency

People comply more willingly when they can see the rules and the results. Transparency has two sides.

First, taxpayers must know what is taxed, how it is calculated, and how decisions are interpreted. Second, citizens should see where the money goes.

Publishing timely, readable accounts of ministries, departments, and State enterprises is part of this. Clarity in the law and clarity in spending both strengthen trust.

Neutrality

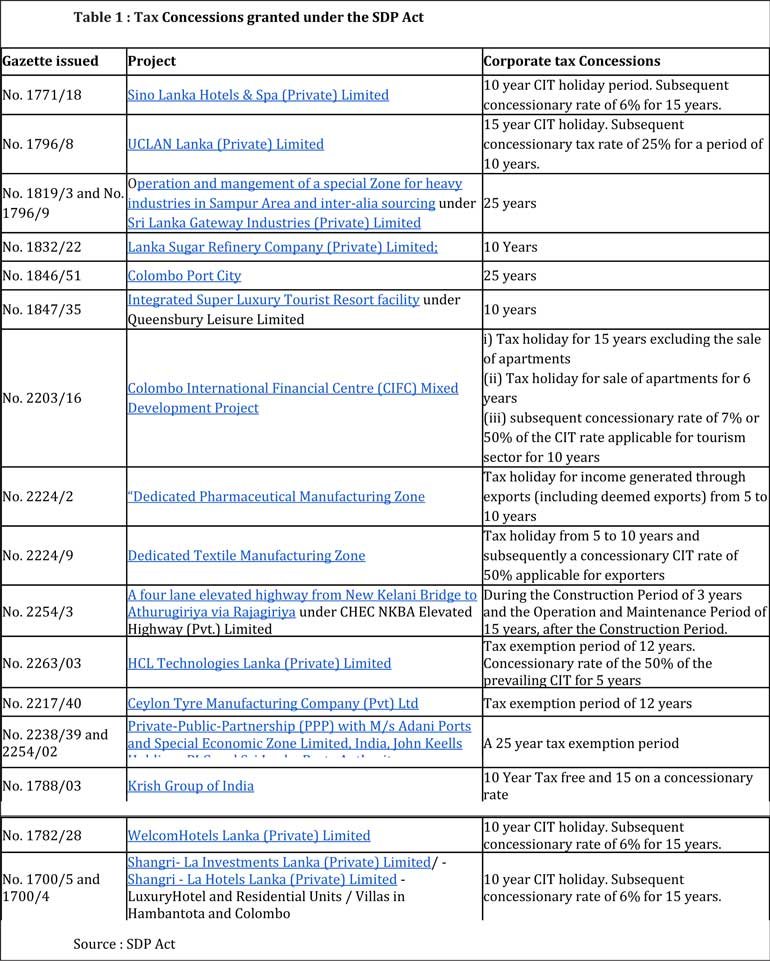

A good tax system does not pick winners or punish losers. It does not tilt the field with ad hoc holidays, selective exemptions, or retroactive changes.

Sri Lanka has seen cases of both, and we paid a price in credibility and lost revenue. Neutrality means the same rules for all, with limited, clearly justified exceptions. When policy favours the connected or penalises the unfavoured, investment shifts from serving customers to seeking favours.

Stability

Frequent tinkering is costly. When rates and thresholds change too often, compliance burdens rise and planning becomes guesswork.

Sri Lanka has repeatedly altered Value-Added Tax (VAT) rates and income tax thresholds in short spans. Stability does not mean never changing. It means changing seldom, with notice, and for clear reasons. Bad policy made in haste is expensive to unwind. The economy needs a steady hand more than clever new tweaks.

Tax competitiveness

Firms and talent look across borders. Our personal and corporate tax burdens should be in line with the region if we want to attract investment and retain skills.

Competitiveness cannot be achieved by wishful thinking. It comes from controlling spending so that rates can be kept moderate. If outlays keep rising, taxes must follow, or inflation will. Either way, growth suffers.

The Sri Lankan context

We are living with the bill for years of high spending and borrowing. Interest costs crowd out other priorities and the system leans on distortionary tools such as border taxes.

The Budget must therefore do three things at once. Hold the line on expenditure, simplify and stabilise the core taxes, and reduce reliance on tariffs and discretionary incentives that undermine neutrality and transparency.

A checklist for the Budget

Are spending commitments realistic, prioritised, and affordable without hidden inflation taxes later?

Do the tax proposals reduce bands, special cases, and compliance steps?

Are all changes clearly explained, with drafts and guidance published early?

Do measures avoid retroactivity and selective holidays?

Do the overall rates and rules keep Sri Lanka competitive in the region?

The bottom line

Revenue matters, but expenditure discipline matters more. If we keep spending under control and align with the basic principles of simplicity, transparency, neutrality, stability, and competitiveness, Sri Lanka can raise what it needs with less harm to growth. If we ignore these principles, we will pay through weaker investment, fewer jobs, and slower incomes.

As the Budget approaches, the call is simple. Keep taxes clean and predictable. Keep spending honestly and affordably. Keep Sri Lanka competitive. That is how a budget serves the people, not just the balance sheet.