By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

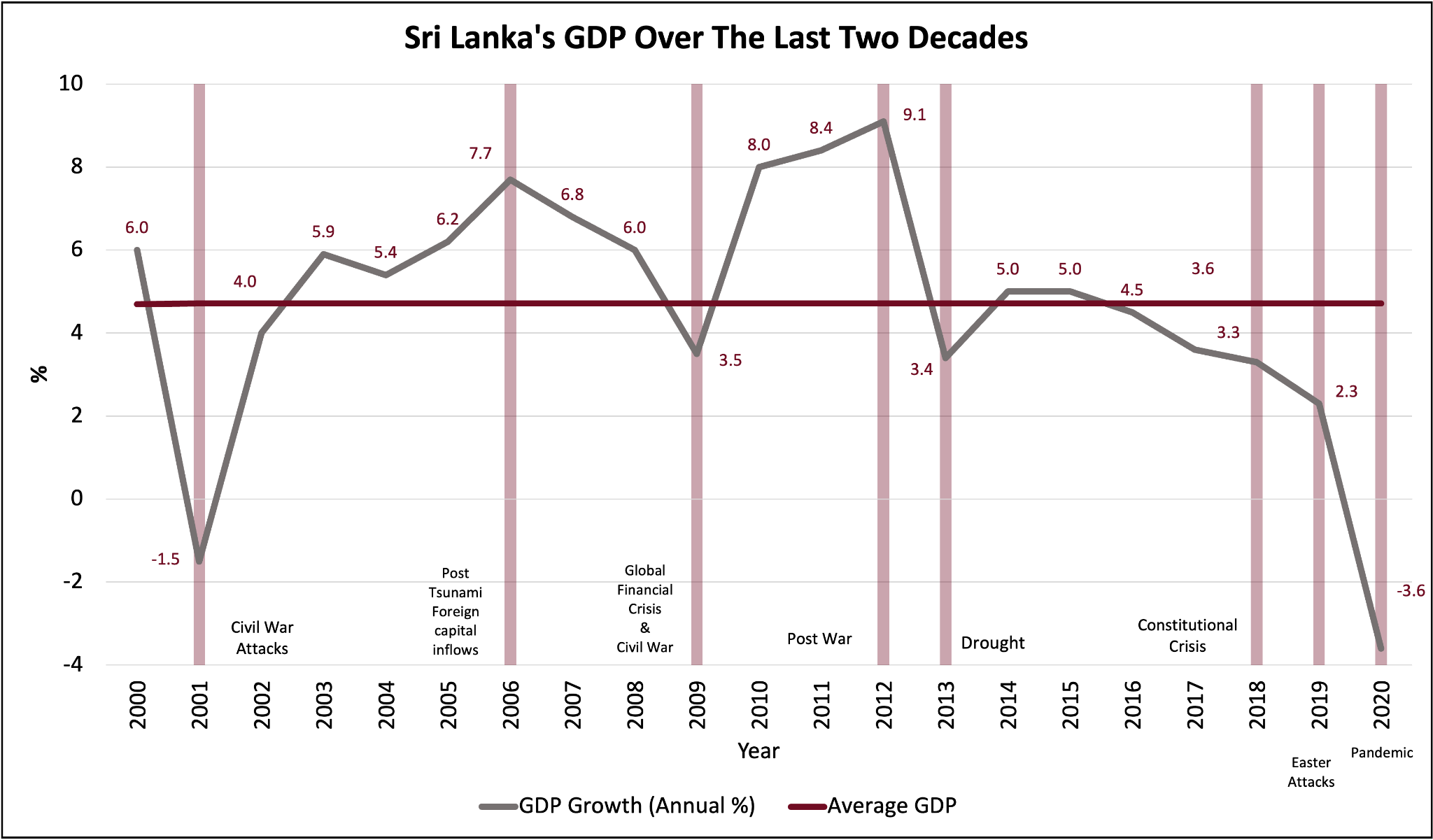

With the final stage of Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring scheduled for next year, the focus must shift decisively towards economic growth. In this context, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s recent visit to India is particularly timely.

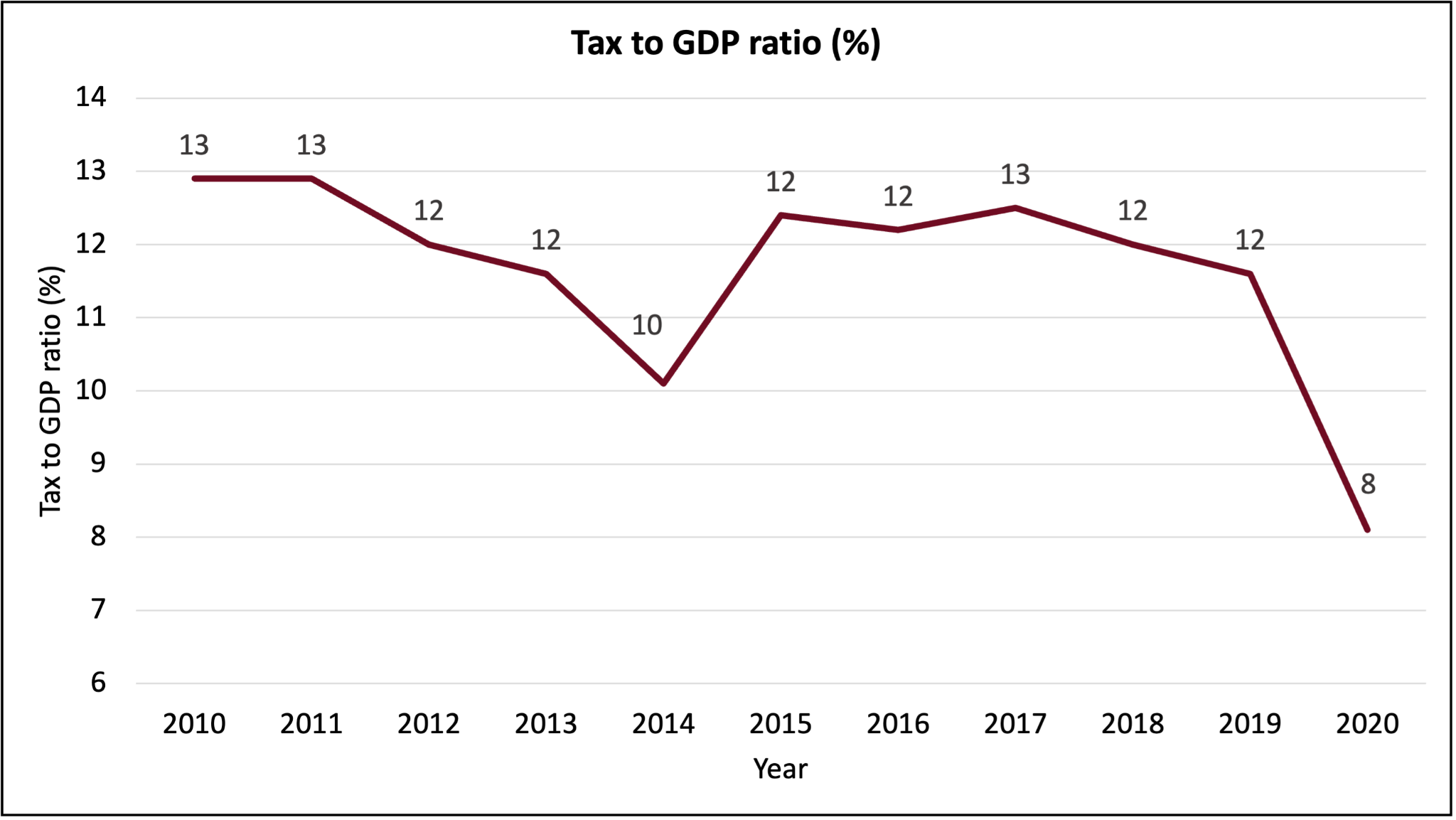

Over the past two years, Sri Lanka has been largely engaged in stabilisation efforts. Higher interest rates and increased taxes were central to this stabilisation agenda, which is fundamentally about avoiding bad decisions rather than actively pursuing the right ones.

Using a cricket analogy, stabilisation is like a No. 11 batsman in a Test match defending the wicket – the goal is simply to avoid getting out, not to score runs.

The next phase, however, demands a proactive growth strategy. Economic growth is less about avoiding pitfalls and more about taking the initiative and making bold moves. If stabilisation is about survival, growth is about thriving; it’s like playing a T20 match where you must play shots, protect your wicket, and actively score runs.

Connectivity represents a key area where Sri Lanka can catalyse growth. Connectivity to the Indian Ocean through maritime routes has been discussed for decades, but connectivity to India deserves equal, if not greater, attention.

India’s rapidly growing middle class presents significant economic opportunities for Sri Lanka. If we are serious about growth, enhancing connectivity with India is a necessity, not an option. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka has been slow to respond over the years. This time, we must be proactive and get the work done.

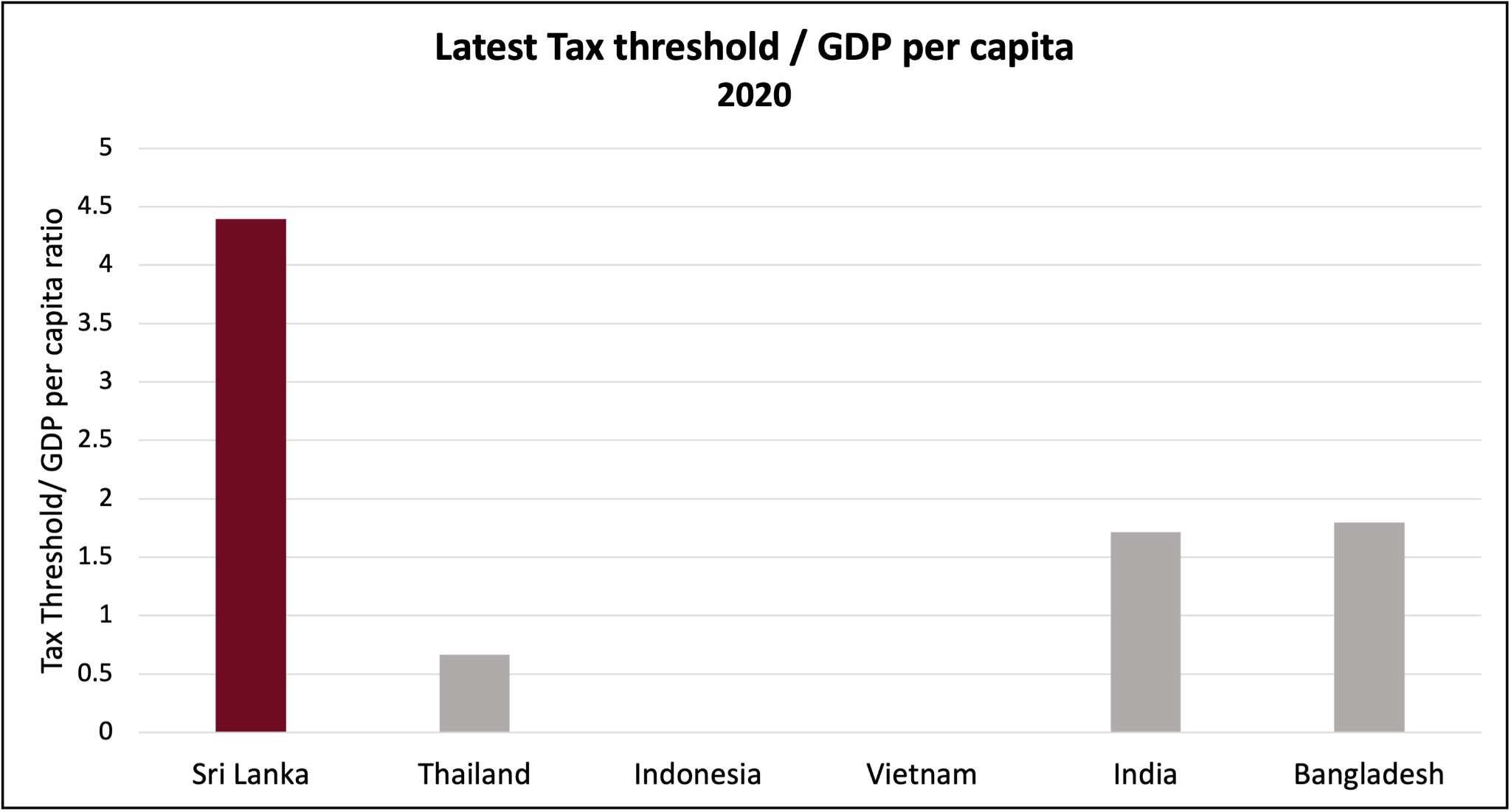

There are already Sri Lankan companies like Damro, MAS, and Brandix, as well as service-sector organisations, that have successfully expanded to India. The fear that Sri Lanka might be at a disadvantage due to its smaller market size is unfounded. In fact, the small size of our market is precisely why we need to integrate with the Indian market.

Among the proposals discussed during the President’s State visit to India, connectivity projects related to energy, transport, and trade stand out as the most crucial. These initiatives provide Sri Lanka access to a market of over one billion people.

Grid connectivity, for instance, has been a topic of discussion for decades but has yet to be realised. Such connectivity would reduce energy costs and create opportunities to export surplus energy, particularly solar power generated during the day.

With South Indian states experiencing peak energy demand during the day due to industrialisation, Sri Lanka could sell excess electricity and, conversely, purchase electricity during the evening when its own demand peaks. This business model would encourage renewable energy investments in Sri Lanka, given the potential to export to India.

Lower energy costs would benefit Sri Lankan industries, including tourism, by reducing production expenses and enhancing global competitiveness. Similarly, an underwater pipeline for petroleum products could significantly cut transportation costs by enabling direct access to South Indian refineries.

A proposed land bridge could also integrate a rail line, telecommunications cables, and grid connectivity, excluding petroleum pipelines, which are expected to connect to Trincomalee’s oil tanks. These connectivity projects will require years of development, substantial investment, and careful geopolitical considerations to avoid supply chain disruptions or tensions.

Economic connectivity with India, particularly in factor markets such as land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship, would drastically reduce production costs and provide access to a larger market. Connecting to bigger markets is essential for economic growth, and India, as a neighbouring economic giant, offers a ready opportunity.

Concerns about independence and fears of interdependence are common among Sri Lankans, but history reveals that Sri Lanka’s culture, including Buddhism, has been profoundly influenced by India. Even today, India accounts for the largest number of tourists to Sri Lanka.

The Government of Sri Lanka must establish competitive investment policies to attract foreign investments with clear cost-benefit analyses. Reviewing joint statements from past State visits shows recurring references to connectivity projects such as the land bridge, Trincomalee oil tanks, and investments. What has been missing is the political will and proactive action to turn these plans into reality.

If Sri Lanka fails to capitalise on this opportunity for economic growth, a second default may become unavoidable, leading to yet another request for assistance from India. The stakes are too high for inaction.