Originally published in Echelon*

By Ravi Ratnsabapathy

A new president has now taken office. How should he set about addressing the concerns of citizens? During the campaign, the candidates and their supporters announced what they plan to do if elected to office. However, most of these lack credibility as they pay no heed to the constraints in the economy.

“THERE ARE THREE SIGNIFICANT PROBLEMS; THE FISCAL/ DEBT PROBLEM, EMPLOYMENT AND PRODUCTIVITY.”

So after the celebration of victory is over the successful candidate should take a long cold shower, grab a stiff drink and become acquainted with some fundamental problems in the economy. Two months ago, former minister Milinda Moragoda helpfully provided a list of seven cold economic truths that presidential candidates must face:

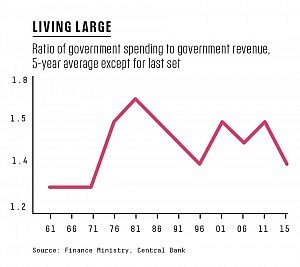

The Sri Lankan government spends twice as much as it earns in revenue. Therefore every year, the Government borrows both domestically and internationally to meet approximately half of its expenditure.

It’s estimated that Sri Lanka requires only 750,000 to 800,000 government employees to provide the services needed by the public. However, the state employs over 1.5 million people. This is one of the highest public servants to population ratios in the world. Besides, to ease employment pressures, the government regularly absorbs the unemployed graduates of local universities. Further, there are now over 600,000 retired government servants, who receive pensions.

Ninety percent of government revenues are required to be spent on servicing the national debt.

Sri Lanka imports around twice as much as it exports.

Sri Lankan Airlines, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Ceylon Electricity Board have become dinosaurs and represent a severe drain on public finances. If left unchecked, these inefficient and costly enterprises can potentially cause the economy to collapse. Vested interests have long dominated these institutions, and no political leader has dared to restructure or reform them.

Although Sri Lanka is considered to be an upper-middle-income country, two million families or nearly 40% of the population is on the Samurdhi welfare programme. A new generation of political leaders must have the courage to re-examine and modernise Sri Lanka’s welfare system.

Twenty five percent of the Sri Lankan workforce is employed in agriculture. Experts say that in an economy such as ours, agricultural employment should be 15%. To manage this transition, Sri Lankan leaders will have to create higher-wage job opportunities in other sectors while bringing efficiencies into the farming sector.”

This is a good summary of critical issues. There are three significant problems; the fiscal/ debt problem, employment and productivity. The main problem is that the government spends far more than it collects in taxes and covers the difference by borrowing. As a result, the debt keeps rising every year, and because we borrow to pay both the capital and the interest, it increases even faster. It is exactly like a household living on a credit card but at a bigger and scarier scale. These problems have existed for decades but have progressively worsened and have now reached a difficult-to ignore point.

“DESPITE CLAIMS TO THE CONTRARY, SRI LANKA IS NOT AN ATTRACTIVE INVESTMENT DESTINATION”

In 2018, total debt service cost was 108% of government revenue, meaning all government revenue (plus a bit more) went to service debt! On average, between 2006- 18 debt service cost was 93% of revenue. What does the government do with this money? The most substantial proportion about 42% of revenue gets spent on salaries and pensions of public servants. Interest on debt absorbs another 37%, the remainder gets spent on various other services, but loss-making state enterprises consume a chunk of it.

This, in a nutshell, is the major problem. What does this mean for policy?

Unless tax revenues are to rise (and who will ever vote for that?), spending must fall.

State sector salaries and pensions are no longer affordable. Politicians cannot promise more state sector jobs or salary increases until finances are on a sound footing. At the least, recruitment and increments may have to be frozen and the difficult question of reducing employment in the public sector faced.

Sri Lanka is producing graduates who expect a government job. During 2005-18, state sector employment grew from 850,000 to 1.3m, partly to “create” jobs for these graduates, adding to the debt problem.

The average overall employability ratio of Sri Lankan university graduates is 54% according to a research paper (Nawaratne, 2012). Arts and management grads have higher rates of unemployment in the country and accounted for 76% and 36% of unemployed graduates (Kanaga Singam, 2017).

The private sector experiences shortages of labour but complain that graduates lack skills. It is insane that the best of our students taught in our universities at public expense complete fifteen years of education but lack employable skills.

About 55% of the graduates are from arts and management while only 28% are from science, IT and engineering. For a developing country, these ratios need to be in reverse.

Primary and secondary education also have problems, not least a lack of school places and an excessive concentration of ‘popular’ schools in Colombo, leading to long commutes for children. Education is supposed to be free, but why do so many parents spend money on tuition? Why do many opt for private “international” schools or private tertiary/university education? These are symptoms of problems in quality and access. The broader question is: can the current system generate people for a knowledge economy?

If public sector jobs are not available, then the onus is on the private sector to create them, which requires new investment. Sri Lanka suffers from low savings rates (around 21% of GDP in 2017/8), meaning it does not generate the same levels of domestic capital for investment that countries with higher growth rates have. To raise the growth rate significantly implies sustaining an investment rate above 30%. For example, Singapore’s investment rate averaged 35% between 1961- 96. This shortfall in investment must be met from overseas.

Despite claims to the contrary, Sri Lanka is not an attractive investment destination, as evidenced by low FDI rates. There are many issues to solve, including policy uncertainty, regulatory problems, land and infrastructure.

In the 1990s privatisations formed an essential channel for FDI, by opening new sectors for investment, notably in telecoms. Public-private partnerships in the port (SAGT and CICT) were also a success. Before the PPP arrangements, between 1997–2000 the volume of containers handled in Colombo port averages 1.7m TEU’s. SAGT started operating in late 1999, CICT in 2013 and by 2018 volumes grew to 7m TEU’s; 66% of which was handled by the two private terminals.

Privatisations and PPP’s are no longer popular, but if an investment is needed and the state is unable to borrow what other options are open? The problem with privatisations and PPPs is that if they are not done through transparent, competitive processes outcomes may be poor. This issue needs to be faced squarely. The recent closed-door deal with the ill-fated Colombo East terminal is not the way forward: the open bid of 2016 which attracted top international shipping lines and operators including the Ports Authority of Singapore was inexplicably cancelled.

The failure to create jobs is why so many of the most talented and motivated people migrate for work. We see contradictory statements by politicians, on one side celebrating the inflow of remittances, on the other bemoaning the social costs associated with migrant labour. No one seems to ask the hard question as to why the local economy cannot create enough jobs to absorb these people.

By some estimates almost 23% of the workforce is employed abroad, if not for this, unemployment would be close to 30%. The failure is not just investment but investment in high productivity jobs that will pay the high salaries that people want. Agriculture is the most unproductive sector of the economy, absorbing 28% of the workforce but generating only 8% of GDP. Politicians promise subsidies or guaranteed prices to ‘help’ this sector but is this feasible in the light of the fiscal and debt issues?

None of these challenges are easily overcome, but unless the reality is faced, Sri Lanka may be heading for multiple crises.

*this article was published in the November issue of the Echelon Magazine, prior to Presidential Elections.