Originally appeared on Daily FT, Lanka Business Online and Groundviews

By Dr Roshan Perera and Dr. Sarath Rajapatirana

Key macroeconomic indicators signal an economic crisis

A reading of key macroeconomic indicators reveals the extent of the economic crisis Sri Lanka is faced with. Indicators in all four sectors of the economy (i.e., the real sector, fiscal sector, external sector, and monetary sector), have been at their worst level in recent years, and in some cases, at levels never before seen in the post-independence history of this country.

Growth was negative in 2020 and continued in the negative territory in the third quarter of 2021. This was obviously partly due to the pandemic as well as the measures taken to curtail its spread. However, growth in Sri Lanka continued to remain subdued while other countries in Asia were firmly on a path to recovery. Macroeconomic instability will continue to negatively impact investor sentiment and growth prospects in 2022. This will be further exacerbated by the impact of the war in Ukraine, as the region accounts for a large share of tourist arrivals and is one of the key destinations for Sri Lanka’s tea exports.

Inflation as measured by the CCPI has reached double digits (15.1% YoY in February 2022). These levels were last seen only during the last stages of the civil war. Many countries around the world have also been experiencing an uptick in inflation due to higher commodity prices, especially energy prices and supply side issues due to pent up demand with the opening of countries.

However, in Sri Lanka, an extremely loose monetary policy due to excessive money printing by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) to finance the Government’s deficit has pushed inflation to double digit levels. Further, core inflation – which excludes food and energy – had risen to 10.9% by February 2022, reflecting the demand pressures in the economy. Food inflation has risen even faster, with the year on change reaching 25.7% in February 2022. The recent outbreak of war in Ukraine sharply increased energy prices, with Brent crude oil prices rising to over $ 100 in March 2022 – levels last seen in late 2014. With domestic fuel prices adjusting to higher international prices, inflation is likely to increase even further.

Meanwhile, the fiscal sector continues to deteriorate. Ad hoc tax changes made at end-2019 resulted in tax revenue declining by around Rs. 500-600 billion in both 2020 and 2021. This decline will continue in 2022 unless measures are taken to reverse this trend. Consequently, tax revenue collection has fallen to the lowest level in history (8% of GDP). This has led to widening fiscal deficits and interest payments absorbing more than 70% of Government revenue.

The significant contraction in revenue with no adjustment to Government expenditure increased the fiscal deficit to 11.1% of GDP in 2020. This is likely to have increased further in 2021. A deficit of this size was last witnessed in 2009 (9.9% of GDP) and 2001 (10/4% of GDP). The sharp decline in revenue and the worsening fiscal position led to international rating agencies downgrading the sovereign, effectively locking Sri Lanka from international capital markets. Hence, the Government resorted to domestic sources to finance the widening fiscal deficit. However, with a cap on interest rates, it fell on the CBSL to do the heavy lifting.

Consequently, money supply rose to unprecedented levels, mainly driven by credit to the Government from CBSL, as the net foreign assets (NFA) of CBSL turned negative for the first time ever. Net Credit to the Government (NCG) in 2021 increased by Rs. 1.454 billion (38.2% YoY) with CBSL being the main provider of credit. Credit to the private sector increased by only Rs. 810 billion (13.1% YoY) during the same period.

The extent of the monetisation of the fiscal deficit is seen by the sharp increase in CBSL’s holdings of Government securities from Rs. 75 billion at end 2019 to Rs. 1,417 billion at end 2021. This has further increased to Rs. 1,529 billion by 11 March 2022. By artificially suppressing interest rates to keep Government borrowing costs low, the CBSL was forced to purchase Government securities not taken up in the primary market. This had increased reserve money (base money) by 35% (YoY) in 2021. The increase in base money would have been even higher if not for the decline in CBSL’s NFA to a negative Rs. 386 billion due to the use of foreign reserves for debt service payments and to support the ‘fixed’ exchange rate.

On the external front, the Government’s large foreign debt repayments and its inability to tap foreign capital markets due to the sovereign downgrade led to the use of foreign reserves for debt service payments. Consequently, the country’s official foreign reserves fell to precarious levels. To address the imbalance in the external sector, the Government restricted imports of many goods. The CBSL also imposed a 100% margin requirement on importation of selected “non-essential” goods.

Notwithstanding these import controls, the trade deficit (the difference between exports and imports) widened in 2021. In addition, in September 2021, CBSL fixed the exchange rate within a band of Rs. 200 to 203 per US Dollar and instructed banks to carry out transactions within this narrow band. Since demand for US Dollars outstripped supply at this “fixed” rate, a black market developed.

On 7 March 2022, when CBSL allowed “greater flexibility” of the exchange rate, the US Dollar was trading at around Rs. 260-270 in the black market. The large deviation between the official exchange rate and the black-market rate led to a significant decline in foreign inflows. Workers’ remittances, which hitherto helped cushion Sri Lanka’s trade deficit, had declined by 23% to $ 5.5 billion in 2021, with the decline continuing in 2022.

Recent policy actions not sufficient to stabilise the economy

To address the deteriorating macroeconomic environment on 4 March 2022, the CBSL revised its policy rates by 100 basis points, thereby raising the Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) to 6.50% and the Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) to 7.50%. In the same monetary policy announcement, CBSL as the Economic and Financial Advisor, proposed several policy measures to be taken by the Government to address the current economic situation, such as;

Introducing measures to discourage non-essential and non-urgent imports urgently

Increasing fuel prices and electricity tariffs immediately, to reflect the cost

Incentivising foreign remittances and investments further

Implementing energy conservation measures, while accelerating the move towards renewable energy

Increasing government revenue through suitable tax increases on a sustained basis

Mobilising foreign financing and non-debt forex inflows on an urgent basis

Monetising the non-strategic and underutilised assets

Postponing non-essential and non-urgent capital projects

However, a few days after this announcement on 7 March, CBSL permitted “greater flexibility in the exchange rate”. Although the CBSL indicated that it was of the view that transactions in the foreign exchange market should be conducted at not higher than Rs. 230 per US Dollar, by 11 March, the US Dollar was trading at Rs. 265/275.

This was partly due to confusion in the market with parallel announcements being made by the Cabinet regarding increasing the incentive payment to Rs. 38 per US Dollar from the current rate of Rs. 10 per US Dollar for repatriations by migrant workers. Maintaining the exchange rate at these levels would require further policy action while restoring the confidence of migrant workers to use formal channels for their remittances.

While the monetary policy tightening cycle has commenced more needs to be done as inflation and inflation expectations remain elevated. The last time inflation was at these levels in 2009, policy interest rates were at 10.50% (SDFR)/12.00% (SLFR) and the 91-day Treasury bill rate was close to 16%. Higher interest rates are also necessary to maintain the interest rate differential given the Federal Reserve Bank of the US has signalled it will continue to raise interest rates to address “surging inflation”. The difference between the current policy interest rates and market interest rates also provides an arbitrage opportunity for investors to make supernormal profits. This opportunity is higher given the large liquidity deficit in the overnight market, which stood at Rs. 704 billion as at 11 March 2022.

Tackling inflation also requires bringing down aggregate demand in the economy. Excessive money printing by CBSL has increased currency in circulation by Rs. 290 billion (59%) from end 2019 to end 2021. The large tax cuts in 2019 have left around Rs. 1 billion in the hands of individuals and businesses. In addition, although workers remittances did not come through formal channels, there was a thriving informal system known as the ‘Hawala’ or ‘Undiyal’ system, by which remittances came into the economy. The increase in cash in the economy has elevated demand for both domestic and imported commodities, thus exerting upward pressure on domestic prices and increasing demand for foreign exchange to support higher imports.

Suppressing imports, particularly of cars, has also left money in the hands of dealers. This excess money in the system is likely to have driven the boom in the stock market and pushed up land prices and the market for second-hand vehicles. The higher money supply in the economy has thus driven speculative activities rather than being channelled into growth-enhancing economic activities. Addressing the build-up of aggregate demand pressures requires, in addition to further tightening of monetary policy, raising taxes and curtailing the monetisation of the deficit through CBSL financing.

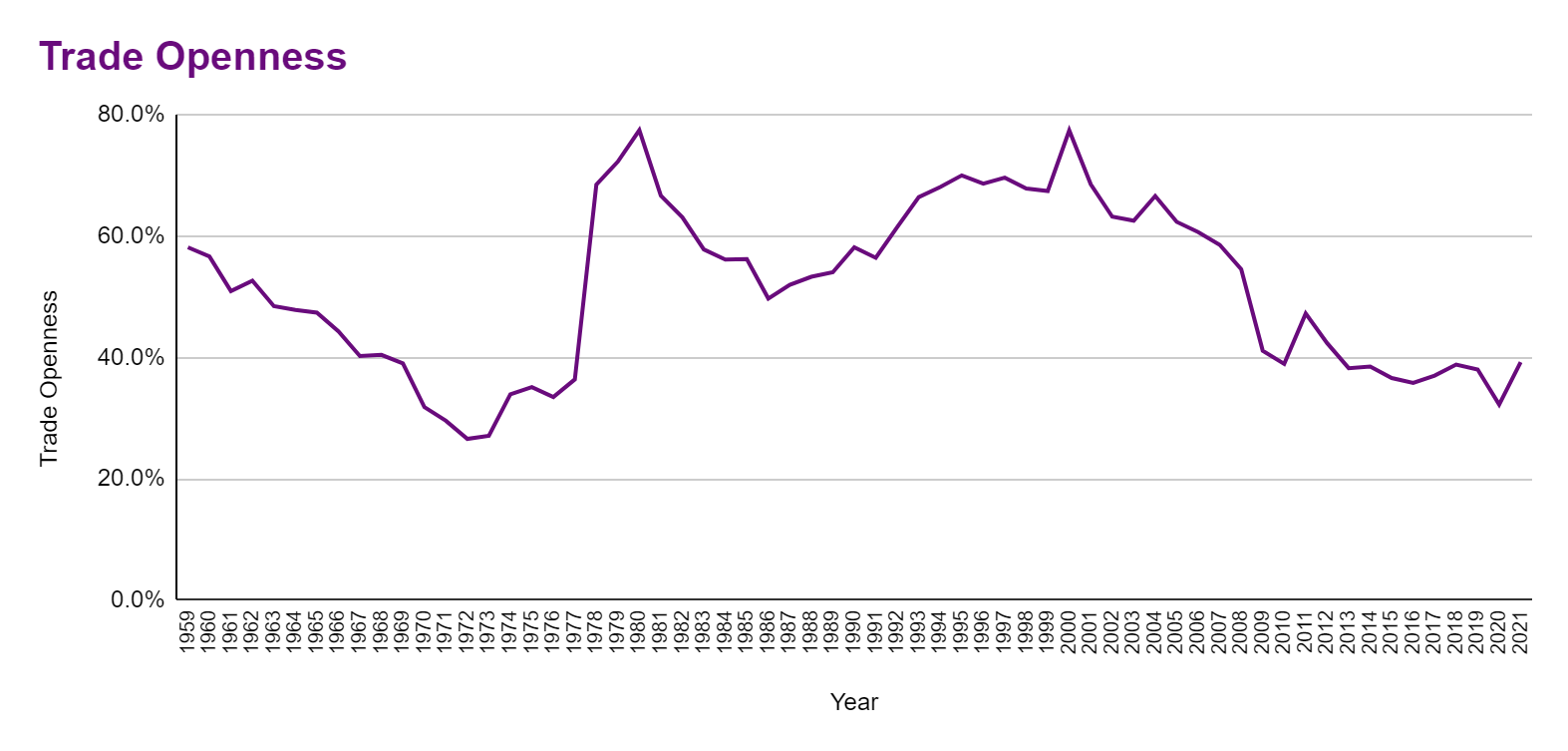

Further, the exchange rate should be the mechanism through which imports are discouraged and exports incentivised. Imports in 2021 increased by 28.5% from 2020. However, the increase from 2019 was only 3.5%. Further, the main increases were in medicines, fuel, textiles, base metals, machinery and equipment, and building materials.

Allowing the market mechanism to determine prices would be the most efficient way to ensure that goods get allocated to their highest use. This is particularly important in the case of fuel, which is priced significantly below cost. Interference in the market mechanism leads to shortages and the development of a black market. There are plenty of examples in the recent past that amply demonstrate the impact of administrative price controls on the availability and quality of goods in the market. In addition, controlling the price or supply of commodities leads to a transfer of “profit” to those who control the market while taxing consumers in terms of time and effort expended to source goods.

Sri Lanka faces twin problems of an internal imbalance with high domestic inflation and an external imbalance with external outflows well in excess of inflows (in other words, a deficit in the balance of payments). The root cause of the twin problems is the Government continuing to run fiscal deficits and financing these deficits through high-cost external borrowing and monetary expansion. Addressing these issues requires policy action on several fronts. However, first, a debt restructuring programme needs to be put in place to give the country some breathing space to stabilise the macroeconomy and to implement growth enhancing reforms.

A comprehensive macroeconomic stabilisation programme and overall economic reform agenda will impact key economic variables; some desirable and some not so. Low-income groups will be particularly affected by these policy adjustments. Hence, attention needs to be paid to ensure an adequate safety net to protect the most vulnerable in society from the fall out of policy adjustments.

The current Samurdhi programme is woefully lacking in terms of adequacy and targeting. There needs to be a more comprehensive social protection scheme. The additional cost of the programme could be funded through savings from the fuel subsidy (which currently disproportionately benefits richer households), reversing the tax cuts and reallocating Government expenditure (1).