Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

The three types of fears we endure as a country

Fear is a universal emotion and we have all come across three major types of fear in our lives. The fear of failure is the most common one that often paralyses us and prevents us from taking action. The fear of success is a lesser-known fear that keeps us from achieving our goals. Finally, the fear of judgement causes us to fear being evaluated by others.

Unfortunately, in Sri Lanka, the fear of reform has encroached upon all three of these personal fears. In public policy, there are currently three primary fears:

Fear of reforming State-Owned Enterprises

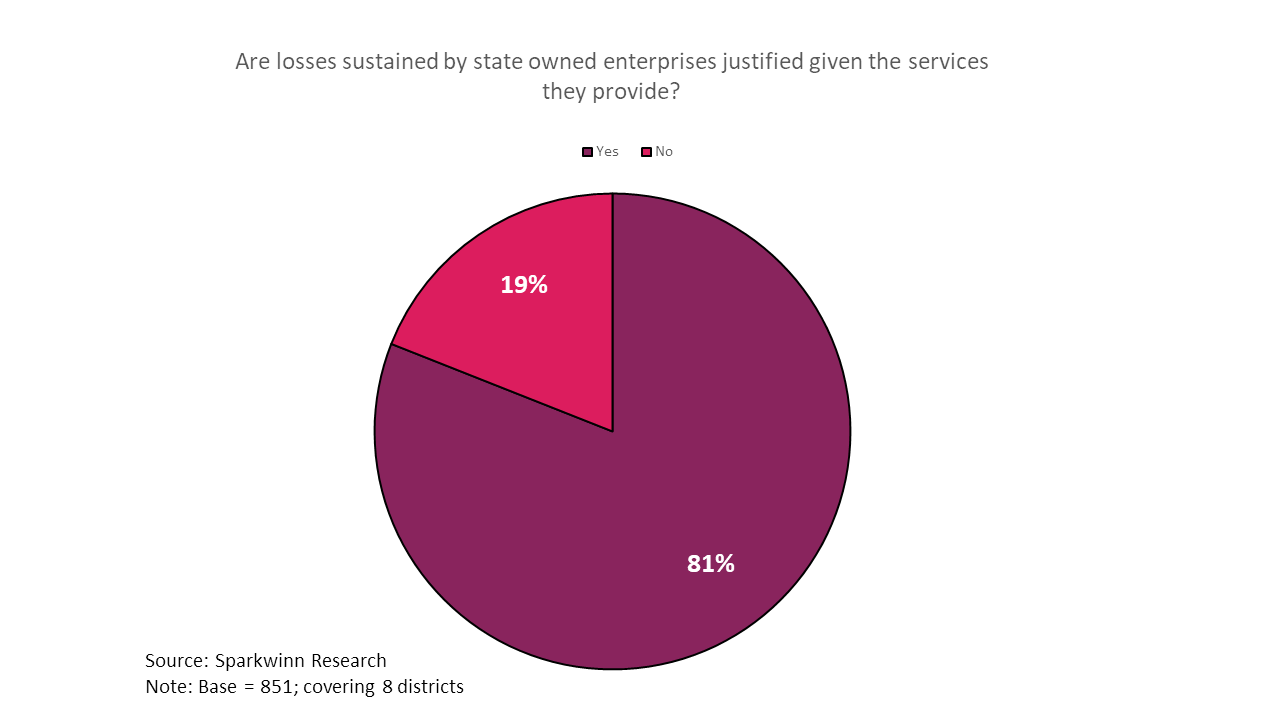

It is no secret that Sri Lanka’s State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) have been one of the main reasons for the country’s economic crisis. Everyone agrees that SOEs need to be reformed, but there are different opinions on how to do it. Some believe that the losses are mainly due to corruption of politicians and political influence against reforming SOEs. Others believe that with capable management, SOEs can become profitable.

However, in my opinion, the absence of competent people to run State institutions and corruption are both symptoms of the absence of a market system.

In a market system, the focus is on making profits and minimising corruption. However, it doesn’t mean everything is perfect; rather, it is geared to minimise corruption and maximise profits. Therefore, opening up the market can help solve this issue.

One key fear that is brought forward is the risk of high prices when the markets are opened. However, based on our experience, prices decrease with the opening of markets and the allowing of more competition.

For instance, Sri Lanka’s telecommunications prices are some of the lowest in the region and the entry of Lanka IOC into the fuel market did not increase prices. On the other hand, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) incurred losses and it had to pass these on to taxpayers. Its losses of Rs. 632 billion over eight months in 2022 will have to be borne by the people of Sri Lanka through the contribution of about Rs. 28,000 per person.

It is evident that the absence of a market system is one reason for the profits not being sustainable, so we always drift back to where we started. The losses of the CPC for the first eight months of 2022 are greater than the allocation for both health and education together, which is about Rs. 550 billion.

Such high losses are indicative that all loss-making institutes, including the CPC, SriLankan Airlines, and the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), should be restructured to reduce the burden on the Treasury and thereby the taxpayer.

The focus is not only on prices but also on the quality and accessibility of the service. In the past, during fuel shortages, people paid Rs. 1,000 per litre on the black market. Therefore, simply claiming that the Government can provide fuel at a lower price is not very logical. We need a Sri Lanka where people can afford and decide what they want to use rather than the Government deciding what we should do. This is the Sri Lanka we envision.

Regulation is crucial and the Government needs to create a regulatory framework to ensure a level playing field. The current Public Utilities Commission Act has provisions, but we need to move towards a competition commission to ensure fair competition.

Fear of competition

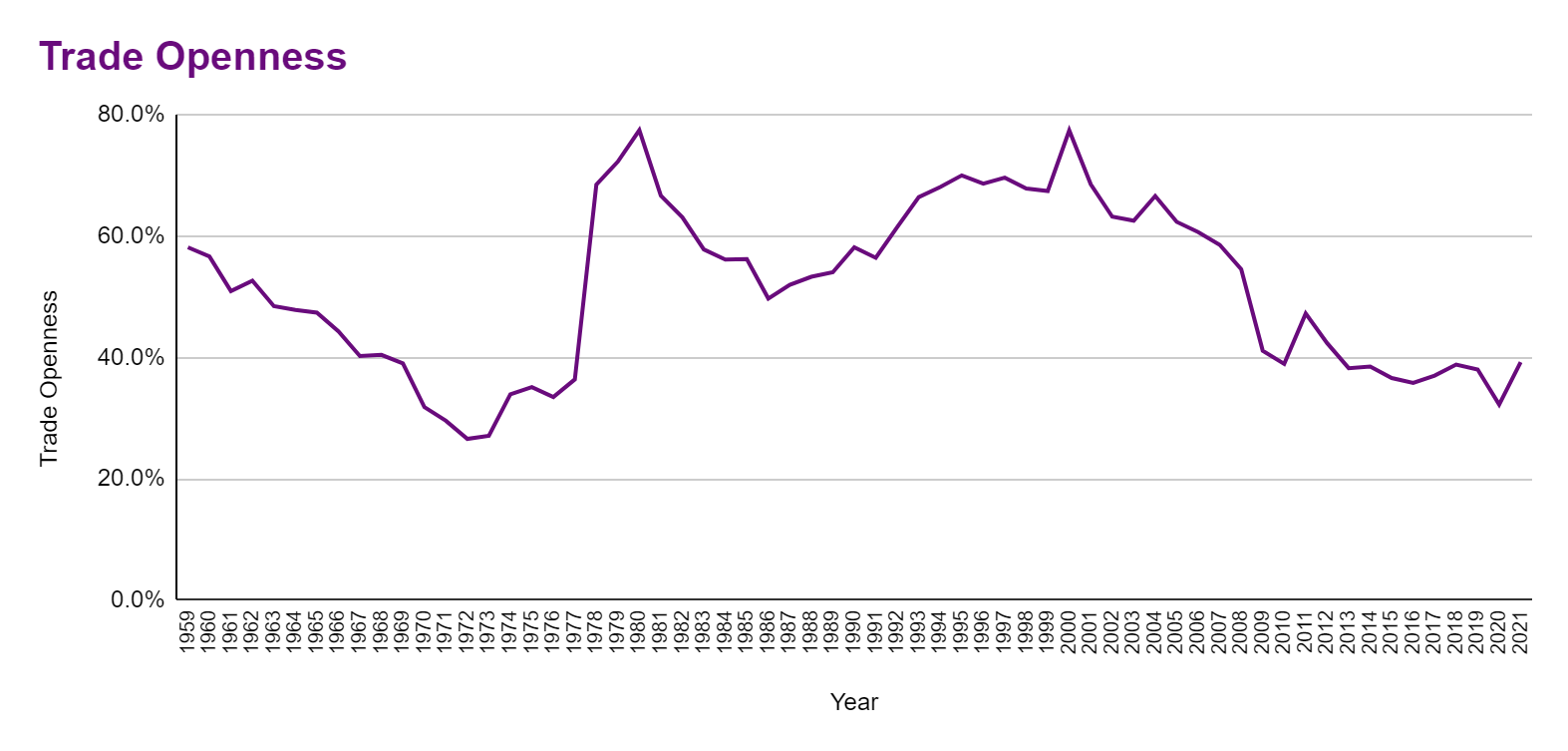

The second fear among Sri Lankans is the fear of competition. We consider competition as one person winning and the other person losing. However, it is a formula where both sides can win. The fear of competition mainly arises in global trade and we often wish to block our competition by imposing high tariffs. However, this has been detrimental to Sri Lankans and to our businesses and we need to move past this fear.

It is also important to remember that competition is the key to maximising consumer welfare. Competition brings in choice to the market and leads to competitive prices. Simultaneously, it incentivises firms to optimise their processes and functions – the key to remaining competitive and profitable. Therefore, competition should be thought of as a win-win scenario where firms are incentivised to optimise their operations and grow while consumers enjoy maximised welfare.

3. Fear of imagining a prosperous Sri Lanka

It is understandable to have concerns and fears about the transition to a more prosperous Sri Lanka, especially when it involves a shift away from a State-dependent model. However, it is important to recognise that a prosperous Sri Lanka can bring many benefits and opportunities for its citizens.

A prosperous Sri Lanka can create jobs and provide opportunities for entrepreneurship and innovation. It can also attract foreign investment and contribute to the growth of the economy. With a thriving economy, the Government will have more resources to invest in areas such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure, which can lead to an overall improvement in the quality of life for its citizens.

It is also important to acknowledge the role of the private sector in providing essential services and goods, as well as contributing to the growth of the economy. While the Government has a role to play in ensuring the safety and wellbeing of its citizens, it is often the private sector that drives innovation and progress.

As Helen Keller once said, avoiding danger does not necessarily lead to safety in the long run. It is important to face our fears and embrace change, even if it is uncomfortable at first. With the right mindset and a willingness to adapt, a prosperous Sri Lanka can be within reach.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.