By Pravena Yogendra

Originally appeared on Newswire, Lanka Business Online, the Morning and Daily News

Most HoReCa channels in Sri Lanka sell a packet of chicken rice and curry at a higher price than a comparative packet of fish rice and curry. The price of a portion of chicken rice and curry is ~30% more than that of a portion of fish rice and curry. This differential has remained over time, as this existed in the pre-crisis environment as well, albeit at low prices.

Is this because of a difference in production costs or due to undue policy intervention by the government?

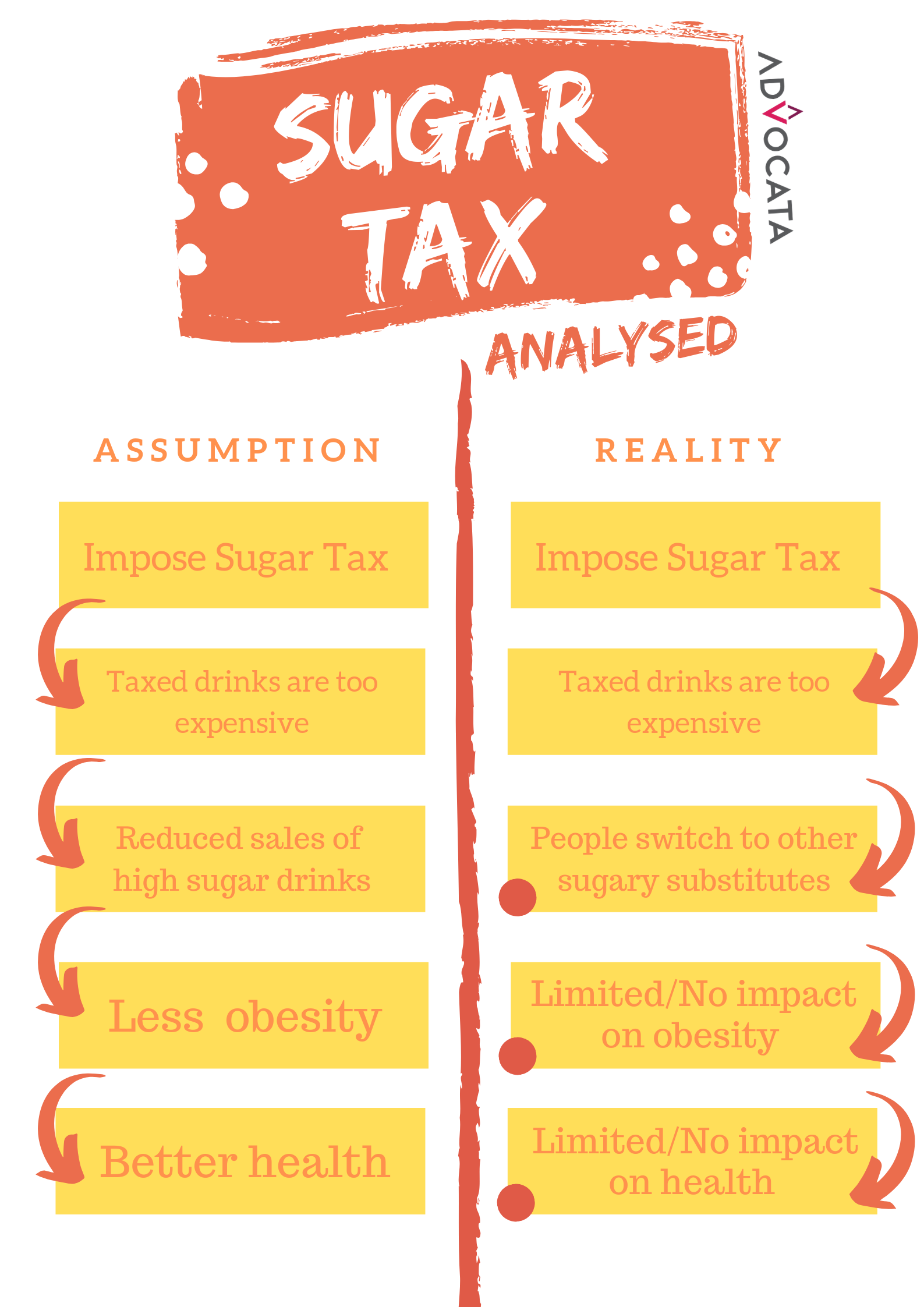

Sri Lanka has a long history of implementing price controls dating back to the 1970s. In recent years, the government has implemented price controls on various essential goods, including food, fuel, and pharmaceuticals. While the resulting lower prices may have been popular among consumers, they have had significant unintended consequences on the economy.

Such price controls create distortions in the marketplace by interfering with the pricing mechanism, thereby preventing resources from being allocated efficiently. The government’s current effort to control the retail price of chicken is a case in point.

Chicken and eggs are the most affordable and culturally accepted meat source in Sri Lanka. The domestic poultry industry produces 240,000 MT of chicken per year, with current per capita consumption standing at 10.8 kg.

The recent economic events, such as the forex shortage and the ban on chemical fertilizers, led to a series of events that artificially inflated chicken prices, making them expensive for regular consumption. As a result, the state felt the need to intervene by controlling the price of broiler chicken.

However, these price controls have only been imposed on the organized/ formal market. Industry specialists classify the domestic chicken market into the formal/ organized market, which accounts for 60% of the market, and the informal/ wet market, accounting for the remaining 40%. Branded broiler chicken producers cater to the organized market, and small and medium-scale poultry farmers cater to the wet market.

The formal market comprises highly productive tax-paying private-sector poultry operators whose products are on par with international quality, health, and safety standards, presenting an excellent opportunity to expand into export markets. This is proven by the fact that these poultry operators supply to sectors that insist on high-quality standards, such as multinational hotels and restaurants operating domestically and abroad.

However, the pricing restrictions imposed on these more productive players have created a situation where the producers cannot pass on their increased production costs to consumers, resulting in them facing compressed profit margins. The short-term implication would be a lower placement of chicks, resulting in a contraction in production, leading to shortages in the market. The medium to long-term significance would be a decline in investments channeled into capacity expansion, which also reduces innovation and technological progress.

It is also important to note that since the wet market players form the larger part of the industry, they are the price setters; and the branded players must follow suit to maintain demand for their products. Wet market chicken prices are mainly determined by the price and availability of other protein substitutes.

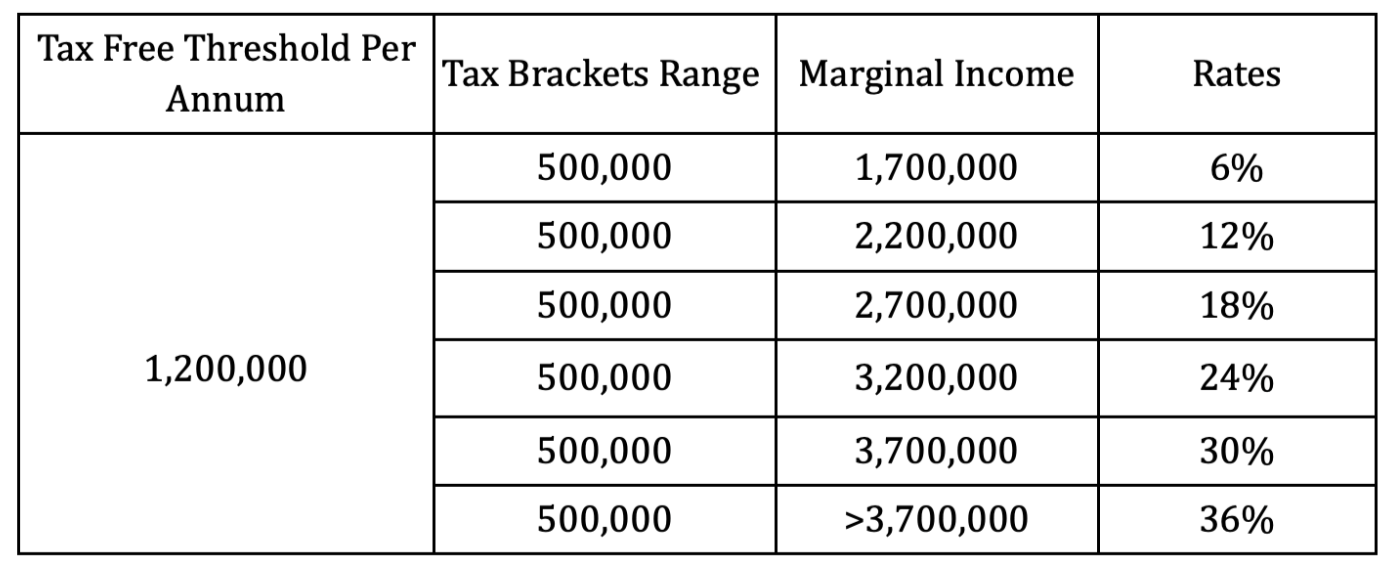

Taxation significantly impacts the retail price of chicken while the burden on fish is lower. Fish is VAT exempt. The major source of costs is labour and entrepreneurship with inputs such as fuel (kerosene) having low tax incidence. In comparison, chicken is subject to VAT, with most producers lying above the VAT threshold of LKR 80Mn. The major cost is the cost of feed which is subject to VAT. It is estimated that both direct and indirect taxes account for 19.6% of the retail price of chicken. The tax treatment between the two alternatives significantly impacts relative prices, disadvantaging chicken over fish. This non-equitable VAT treatment of the two substitutes is expected to be further exacerbated in January 2024 as VAT rates are set to increase by 3% to 18%.

Although the state is focusing on controlling the final retail price of chicken, the real issue lies in inflated input costs. Poultry producer’s input costs have escalated due to the depreciation of the rupee, higher staff costs, and higher admin costs. However, manufacturers' main point of contention has been the feed cost.

Maize is the largest component of poultry feed, accounting for ~60% of weight and 45% of feed cost. Although nutritionists discovered that rice can be used as a 1 for 1 substitute for maize, its utilization for purposes other than human consumption remains highly regulated, resulting in minimal availability

Domestic maize prices are currently at abnormally high levels as maize production is still reeling from the after-effects of the fertilizer crisis.

Sri Lanka's annual maize requirement is ~500,000 MT, of which ~300,000 MT are produced domestically. Roughly ~210,000 MT are cultivated during the primary Maha season and another ~90,000 MT during the secondary Yala season. The yield on maize cultivation by smallholders is currently 1.5 tons per acre. However, industry experts believe that a yield of 2.5 tons per acre can be achieved if correct farming practices are deployed. A kg of maize currently retails at ~LKR 160. Pre-crisis, it used to retail at LKR 45.

Industry practitioners believe that several efforts can be undertaken to improve the productivity of domestic maize cultivation, thereby bringing costs down. A higher yield can be achieved if proper agricultural land is utilized. Currently, maize farming is conducted on encroached forest land. Due to red tape, the 17,000 hectares allocated by the Mahaweli scheme for agriculture remain largely unutilized.

Farmers can also yield more if maize fields are irrigated instead of rainfed. Experts also believe that the right farming practices are not undertaken as proper soil analysis and spraying are not performed.

Currently, maize can be imported from Pakistan at USD 250-260 per tonne, which works out to LKR 110 per kg, including a special commodity levy of LKR 25. The SCL is a contentious tax and was even highlighted in the recently issued IMF technical assistance report, citing corruption.

The SCL is a seasonal, quantity tax imposed on certain essential commodities as a composite tax in lieu of other prevailing levies such as customs duty, VAT, EDB, CESS, Excise duty, PAL, and NBT. The SCL has come under fire as it is subjective and arbitrary, imposed at the discretion of the finance minister, creating uncertainty among industry stakeholders.

In the case of maize, seeds imported for the purpose of animal feed production have been subjected to SCL during lean production periods, to facilitate imports. When the SCL is not in effect, a general duty of 20%, CESS of 30%, VAT of 15%, and SSCL of 2.5% are imposed at the border.

Therefore, not only does the SCL drive up the cost of chicken, but it also creates uncertainty due to the unpredictability and subjective nature of the tax

Maize continues to remain a controlled import that can only be imported by license holders. Licenses to import maize are issued by the import controller based on recommendations issued by the agricultural minister, who issues said recommendations based on his view of the industry’s maize requirement.

Sri Lanka's organized players are second to none in the poultry breeding process- they have adopted international quality standards regarding feed conversion ratio, mortality rates, farm productivity, etc., putting them on par with foreign players. In addition to being highly efficient, the industry also contains sufficient productive capacity to be self-sufficient, thereby rendering the case for importation redundant.

The industry also maintains biosecurity standards and adheres to industry and farming best practice to ensure healthy, safe, and high-quality output that match the quality and certifications required by export markets.

The government should step back from intervening in the market for both maize and broiler and allow the magic of the hidden hand to do the heavy lifting. Not only will this lead to more stable prices, but competition will drive further innovation and productivity improvements, leading to more production and lower prices.