By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

The National People’s Power’s (NPP) maiden Budget will be presented to Parliament tomorrow (17). Ideally, a budget should not contain surprises – neither on the income front nor on the expenditure front. Government expenditure is the real tax burden on people; they ultimately bear the cost through taxes, inflation, or both.

Generally, a budget consists of two key components. The first is revenue and expenditure, while the second is the policy direction of the Government. This time, the business community is particularly focused on the latter, as it is evident that income and expenditure must align with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme.

Adhering to IMF targets

The 2025 Budget has no alternative but to adhere to the parameters set by the IMF. While micro-level details and specific projects may change, key indicators such as gross financing needs, Government revenue-to-GDP ratio, primary balance, and debt-to-GDP ratio must be maintained as agreed under the IMF programme.

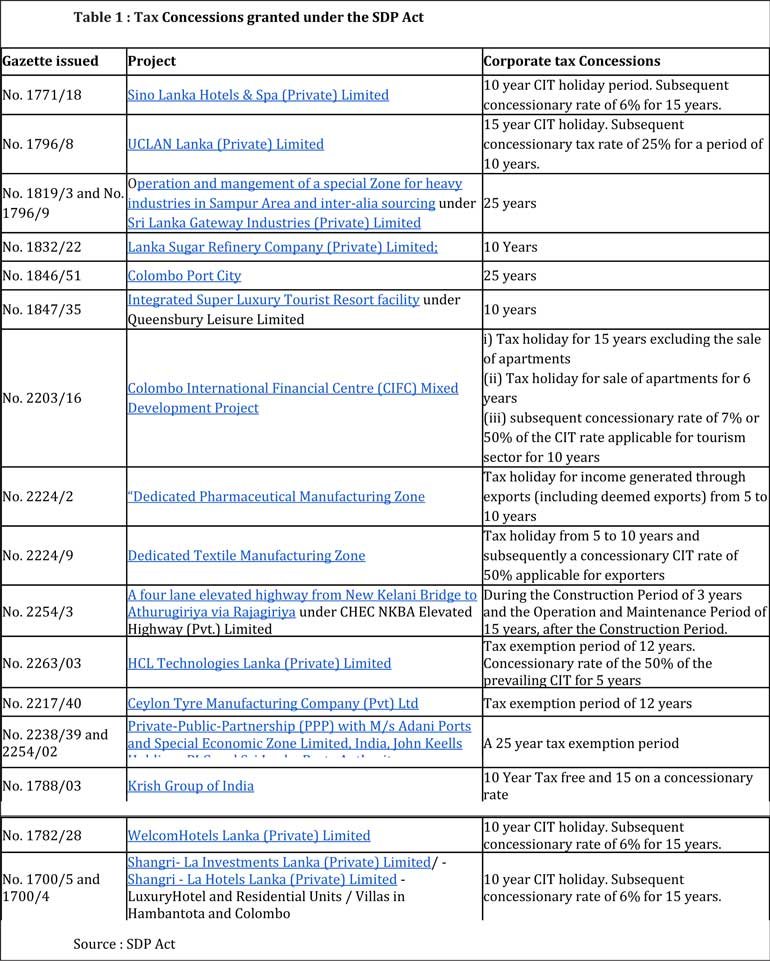

Additionally, the previous Government introduced new legislation under the economic transformation framework, covering many of the IMF’s targets. Achieving a Government revenue target of 15.1% of GDP will be a major challenge. Value-Added Tax (VAT), corporate tax, and income tax have already reached their upper limits, leaving limited scope for further increases. The Government is likely to bridge part of the revenue gap through vehicle importation.

When governments face revenue shortfalls, ad hoc taxes or sudden tax increases are common, often targeting sin industries such as tobacco and alcohol. However, the Budget must adhere to sound tax principles, ensuring simplicity, transparency, neutrality, and stability.

The focus should be on simplifying the tax system and improving the efficiency of tax administration, as poor administration is as harmful as a bad tax system. Any unexpected changes in revenue policies could harm businesses, erode investor confidence, and slow down the economy. The best way to achieve the 15.1% revenue target is through efficiency measures and broadening the tax base.

Over 50% of recurrent expenditure towards interest payments

Sri Lanka has little control over its expenditure, with over 50% of spending allocated to interest payments. In 2023, approximately 90% of tax revenue was spent on interest payments.

Currently, Sri Lanka has one of the highest interest payment-to-revenue ratios in the world, raising concerns about the possibility of a second debt restructuring. Post-debt restructuring, the Government has minimal room for fiscal adjustments.

While Government employees and various sectors may expect relief packages, the reality is that there is no fiscal space to accommodate such demands. It is true that salary structures for senior Government positions need improvement to attract the right talent, but this can only be achieved by restructuring the lower levels of the public service, which absorb the bulk of the salary bill.

Another solution is to drive economic growth and increase labour force participation, reducing the proportion of Government employees relative to the total workforce. Blanket salary increments are difficult to implement without compromising capital expenditure, which is crucial for long-term development.

Currently, 20% of recurrent expenditure is allocated to salaries and wages, while pensions account for approximately 8%. Given this context, expecting significant relief packages is unrealistic, and any attempt to provide them could lead to long-term economic instability.

Investment should prioritise healthcare, education, social protection

Government spending should prioritise critical sectors such as healthcare, education, and talent development. However, expenditure in these areas – including the ‘Aswesuma’ social safety net – was lower than expected last year.

The IMF has pointed out that Sri Lanka did not fully allocate the funds intended for ‘Aswesuma,’ which serves as the primary social safety net for the country. Ensuring proper allocation to these essential sectors is crucial.

Focus should be on structural reforms

Rather than solely focusing on balancing income and expenditure, the Government should use the Budget as an opportunity to set a clear policy direction.

Key areas requiring structural reforms include land policies, labour laws, the export sector, and energy markets. These reforms are fundamental to Sri Lanka’s economic growth, as the country’s challenges are largely structural rather than issue-specific.

We will have to wait until tomorrow to see the extent to which the Government seizes this opportunity. Instead of expecting widespread relief measures, the public should push for meaningful policy reforms – an essential step for securing Sri Lanka’s future

(Sources: CBSL, Advocata Research)

(Sources: CBSL, MOF Annual Report, Advocata Research)