Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

Economic crisis fueling migratory instability

Long queues to sort out passports and visas led many people to believe that Sri Lanka’s economic conditions were driving citizens away.

A survey by the Institute for Health Policy (IHP) conducted on 746 adults revealed that 27% of Sri Lankans are indeed willing to migrate if presented with the opportunity. According to the survey, 48% of those aged between 18-29 are considering migration, and 16% have started preparations to leave. The findings also revealed that 21% of those aged between 18-29 too have started preparations to leave. Further, 22% of women in the sample are considering migration, with 12% already having started preparations. There is no doubt that this survey is an indication of the critical situation Sri Lanka’s economy is faced with.

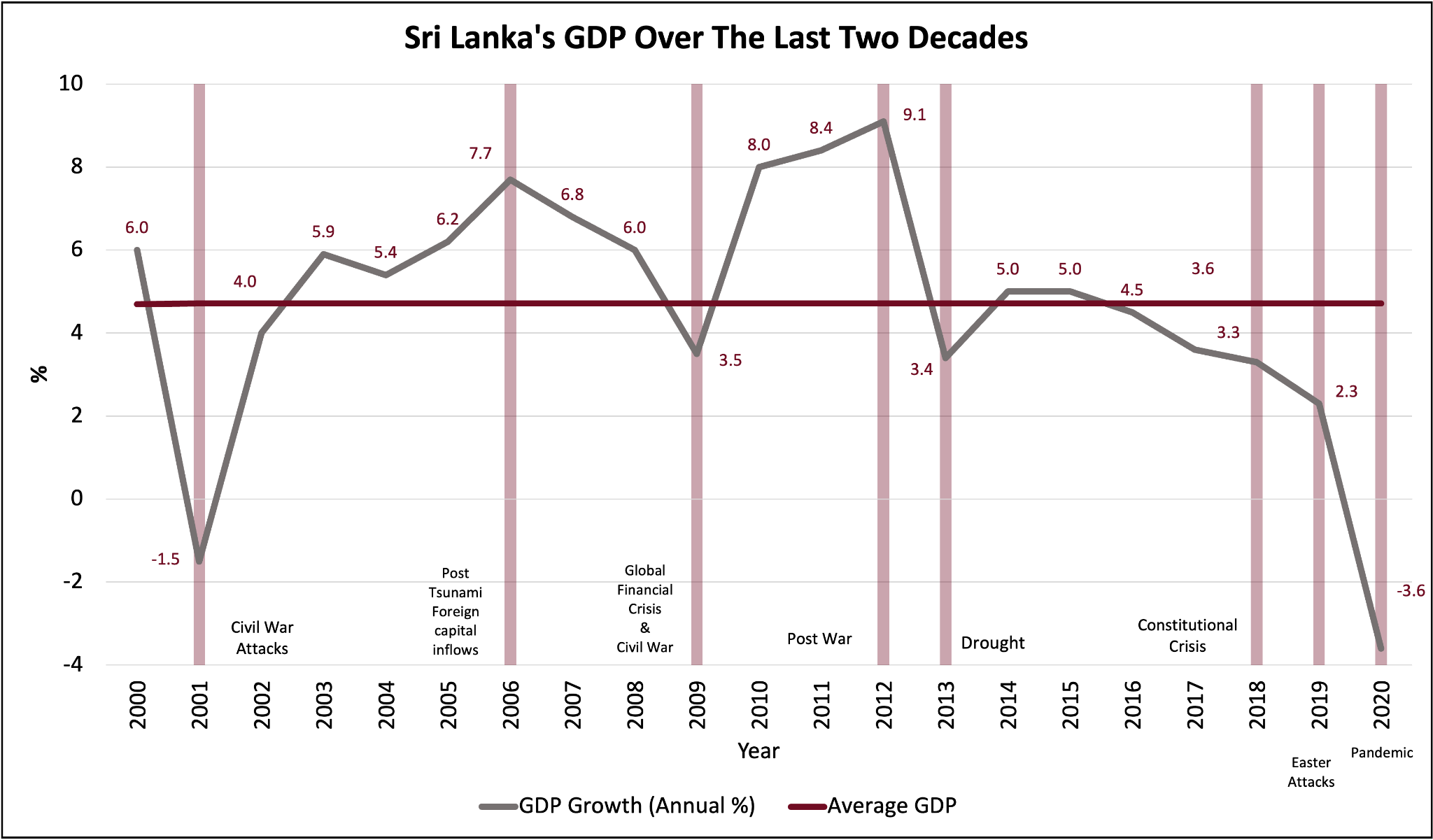

Sri Lankans have experienced the economic impact of various environmental hazards such as the tsunami, floods, landslides, and droughts. The economic impact of the ethnic conflict that lasted for 30 years and the impact of the Easter Sunday attacks on tourism were two other shocks that Sri Lanka has had to endure. However, the impact of an economic crisis is not felt overnight. The crisis we are in now has brewed at a slower pace and has hit us much faster than we expected. People often fail to understand the gravity of an economic crisis, and that in itself is rather dangerous.

The country is at a risk of losing more lives due to medicine shortages. Therefore, it is evident that measuring the impact of the crisis is quite difficult. However, this will indeed be felt in the form of increasingly poor quality of life and loss of hard-earned wealth across the board.

Economic crises physically manifest in the form of price hikes on essential items, shortages, and lower income levels. Shortages of LP gas, cement, and sugar is indeed an indication of the magnitude of the crisis we are in. Therefore, it is quite self-explanatory that people have increasingly felt the need to seek a better quality of life and opportunities outside Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka has experienced this before, during the ethnic conflict. Many people from the North and East fled to the West. These people didn’t leave Sri Lanka because they loved the country any less, they left because it was becoming increasingly hard to live here.

According to the aforementioned IHP survey, about 43% from the Northern Province desire to migrate, while 38% from Eastern Province desire to migrate. However, only about 2% have started preparations for migration in the Northern Province, indicating the gap between the desired action and resources.

The pressure is mounting up for the Government, and recently even his Excellency the President and the Prime Minister both admitted and highlighted the concern of youth migration. So, it is clear that the pressure felt at grassroot level is being noticed by the decision makers of the country. However, this is happening while the rising cost of living and worsening economic conditions are taking a hit at people’s consumption patterns.

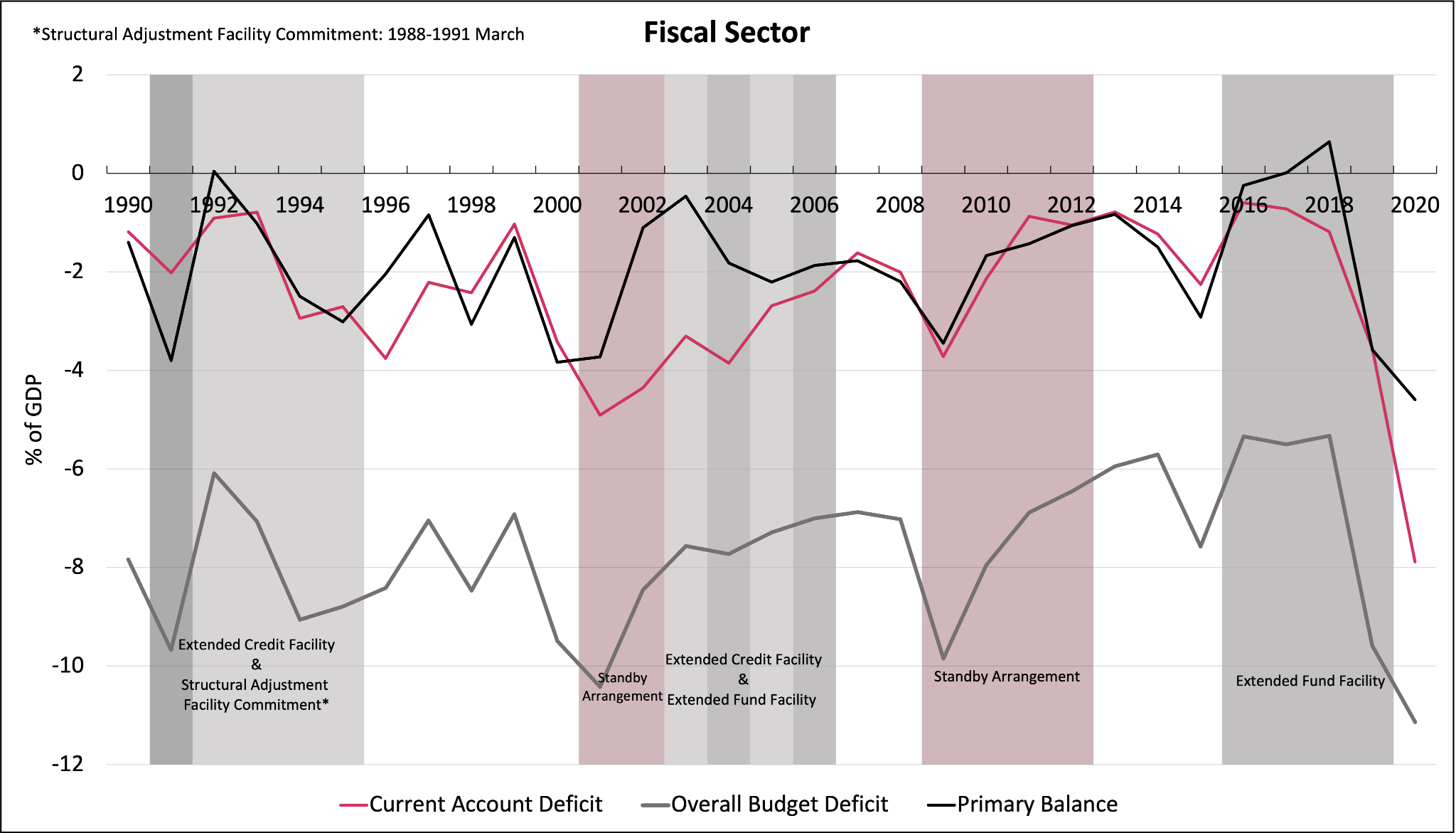

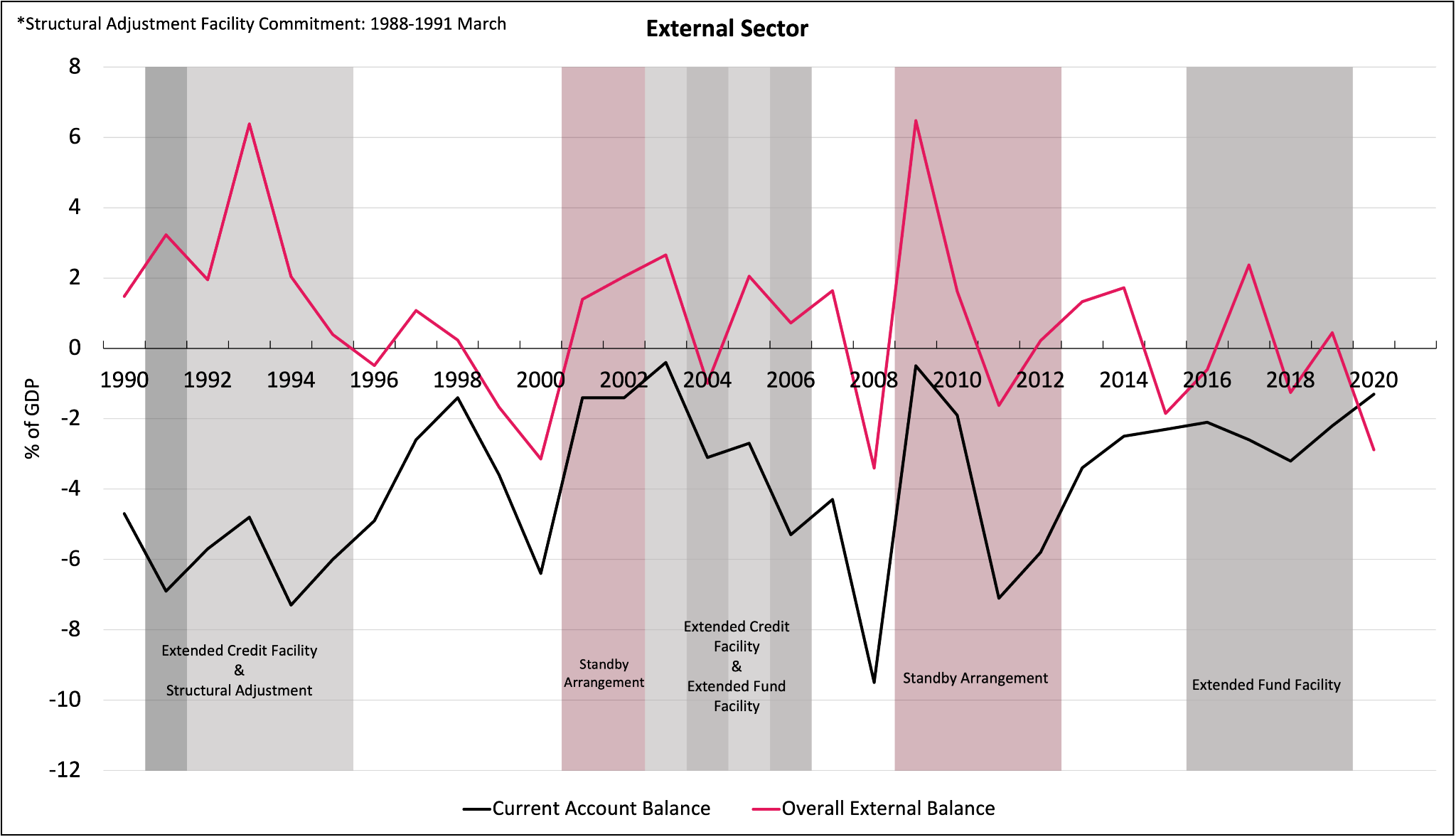

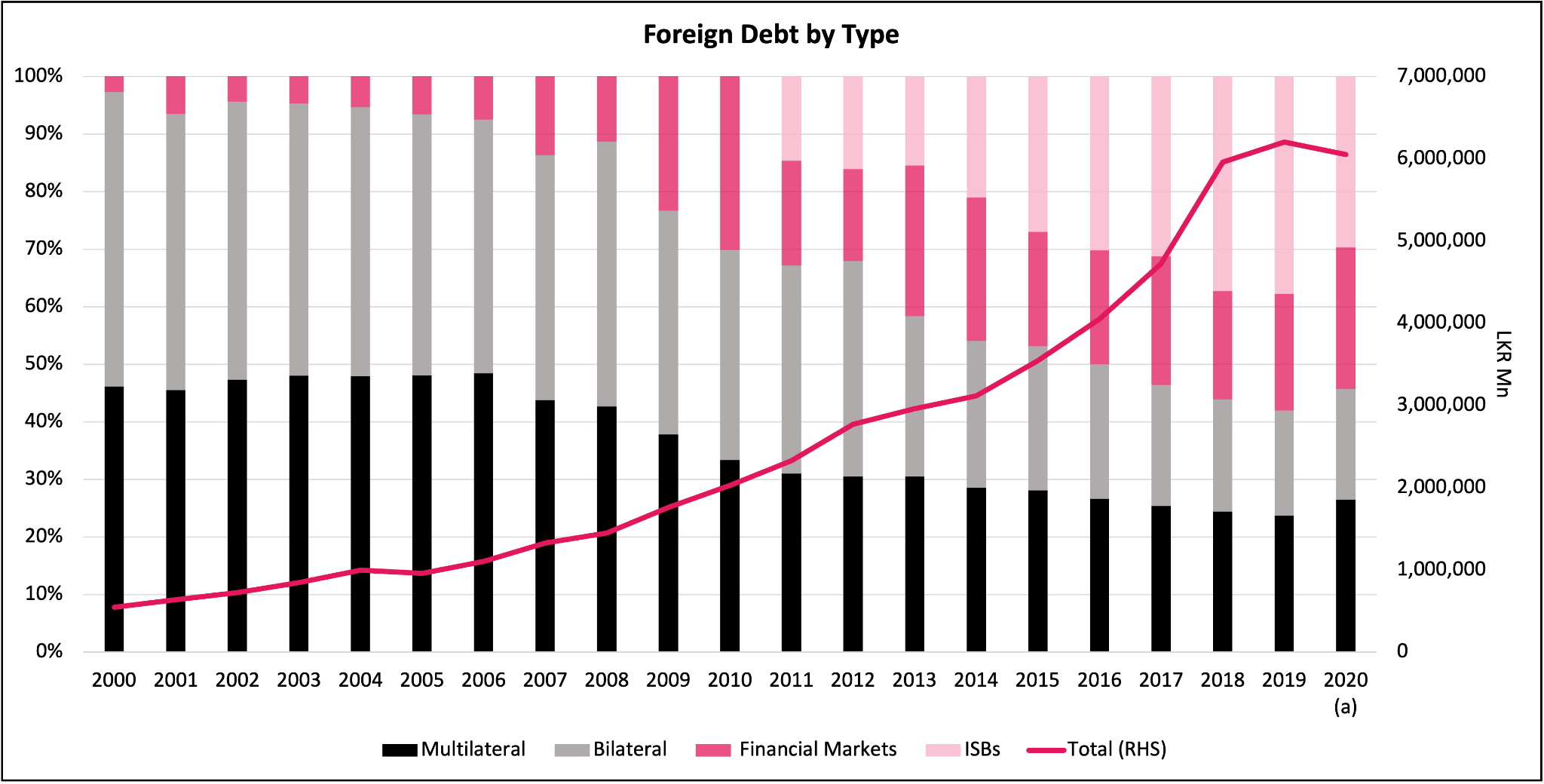

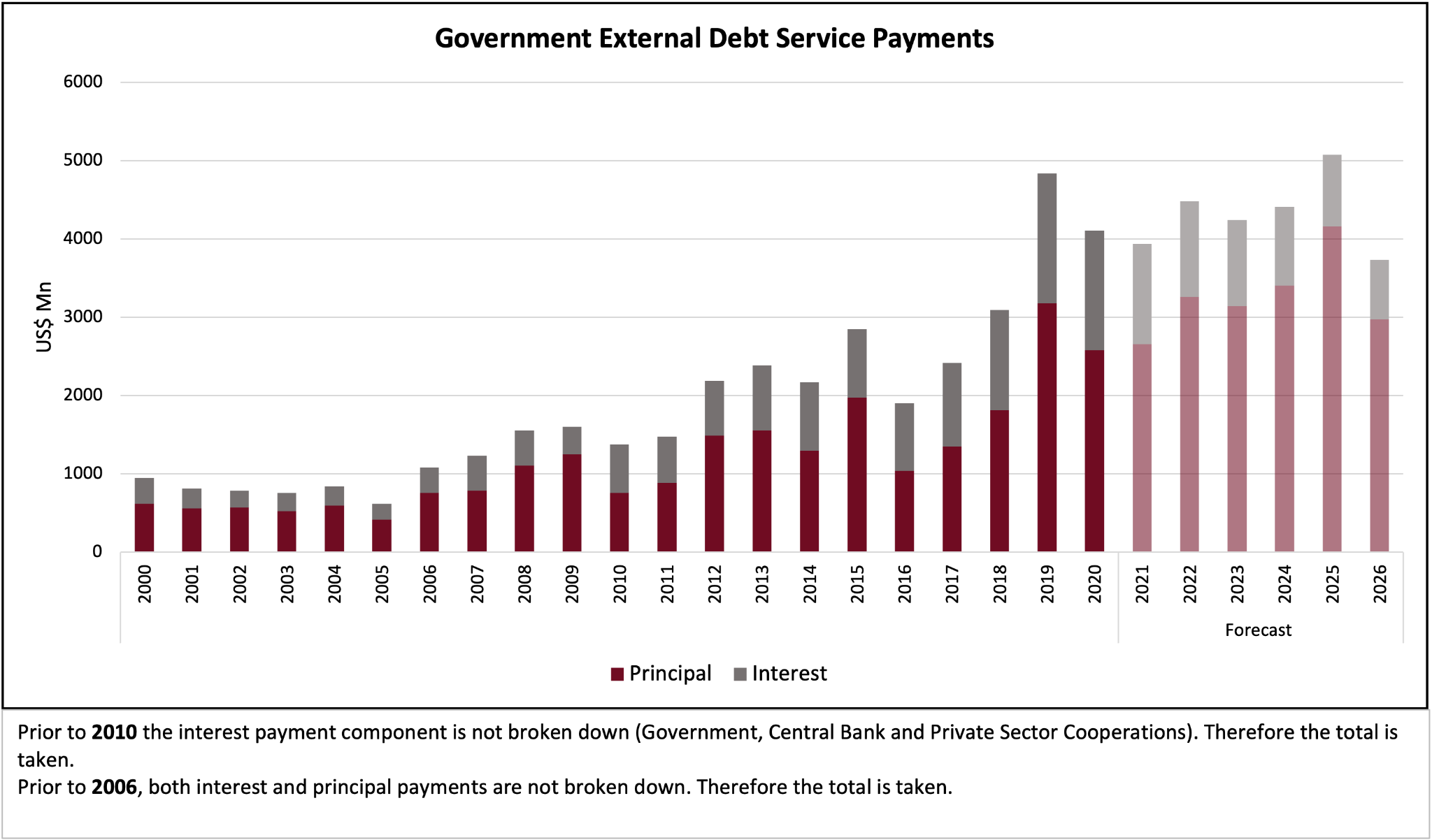

The pressure is such that the Government is now considering IMF support, which they have been avoiding thus far.

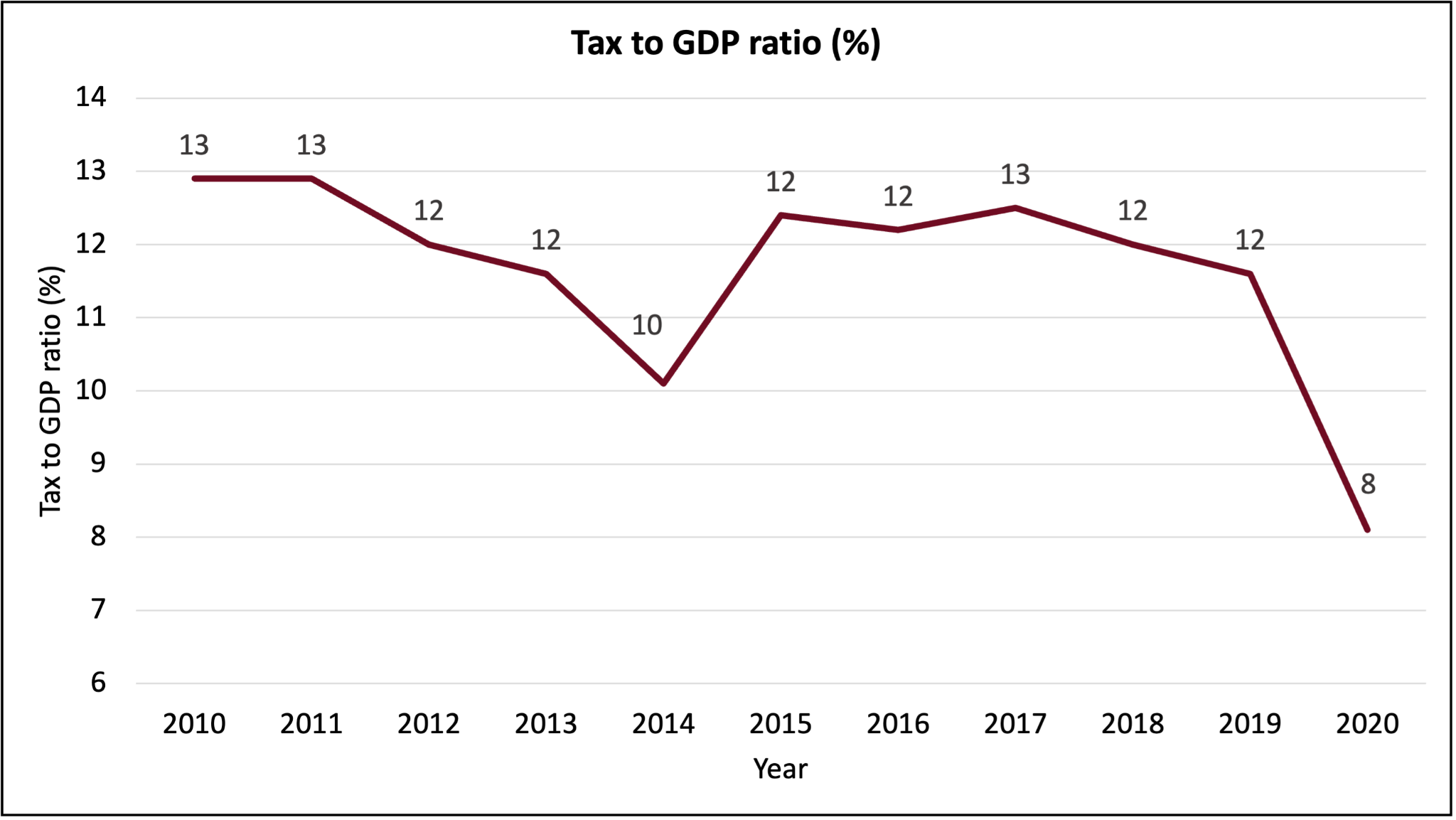

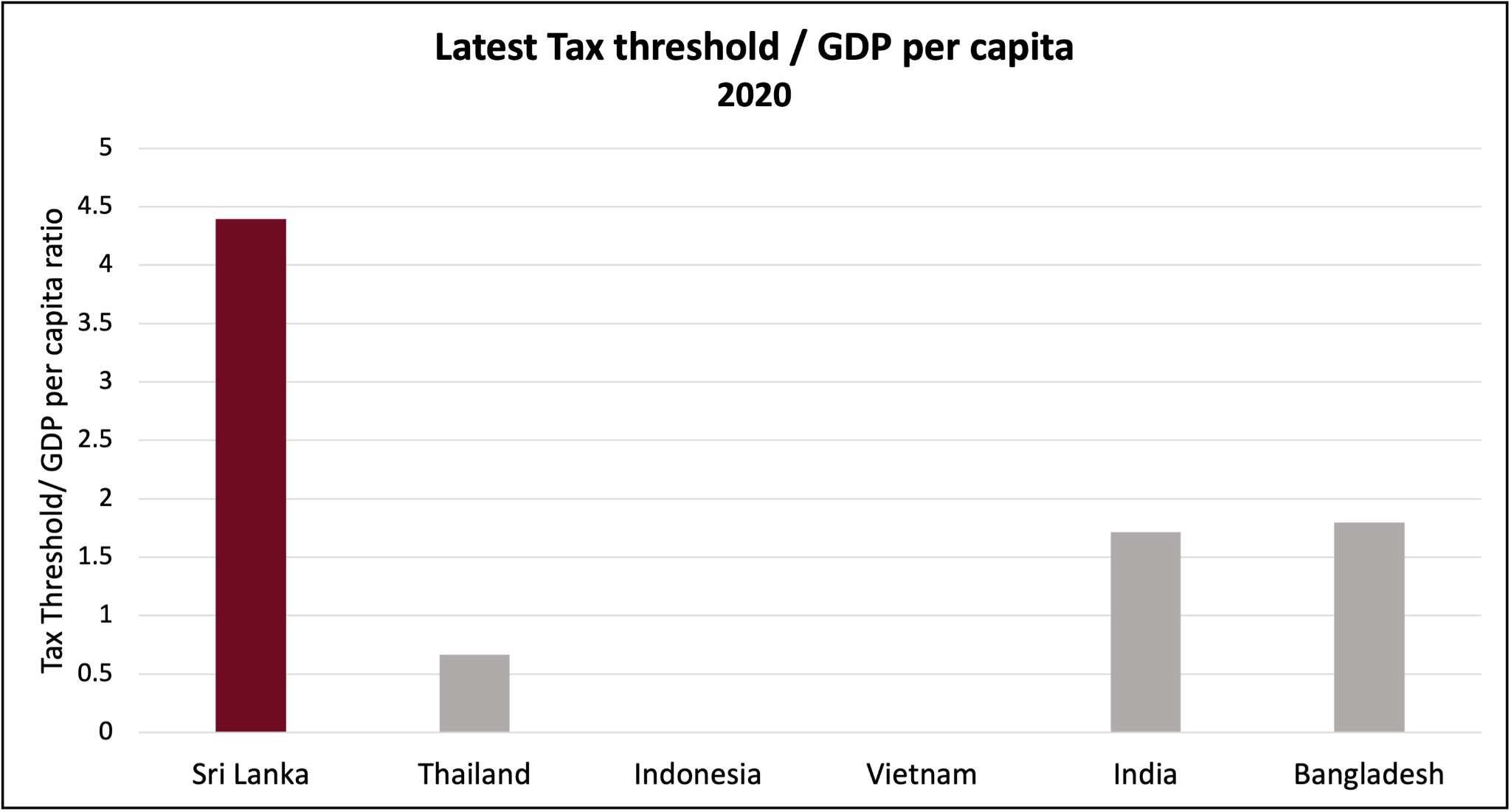

All main indicators in our economy so far are not pointing towards any stronger recovery to overcome the crisis we are in.

In my view we are already too late. The only silver lining I see is the opportunity to restructure the economy. However, reforms in an environment which is unprepared for an economic overturn will be painful. It will take a longer time to recover, and it may have unintended consequences sociologically.

The Budget has pronounced some reform measures such as restructuring the public sector and reforming State Owned Enterprises. However, these reforms were contradicted by short sighted proposals to further recruit more than 50,000 government workers, etc.

One out of every two people expecting to emigrate and one out of four adults expecting to emigrate should not be taken lightly by the Government. It is a symptom of a bigger problem. Sri Lanka needs a credible plan to face the economic crisis we are in. Otherwise, those who have the capability and capacity to navigate through the storm will abandon the sinking ship or consider sailing to the land of Kangaroos through illegal means.

References

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.