Originally appeared on the Morning

By Thilini Bandara and Niumi Amarasekara

Introduction

In the current context of food insecurity, building a resilient agri-food supply chain is crucial for Sri Lanka. The agri-food supply chains are a set of activities involved in a “farm to fork'' sequence including farming, processing, testing, packaging, warehousing, transportation, distribution, and marketing. So far, the supply chains have been providing mass quantities of food for the country’s growing population. However, the supply chains are plagued by a number of issues stemming from within and outside the supply chain. Hence this article sheds light on various inefficiencies prevalent in the agri-food supply chain and the way forward to establish a more resilient supply chain.

Overview of agri-food supply chain in Sri Lanka

Agri-food sector plays a major role in the Sri Lankan economy. It is a key source of food supplies which comprises a complex system of supply chains involving farmers, distributors, processing firms, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

Figure 01: Flow of agri-food supply chain

Issues in the agri-food supply chain sector

The country has been experiencing inefficiencies within its agriculture sector due to various issues stemming from within the supply chain. For instance, Sri Lanka annually loses 270,000 metric tons of fruits and vegetables along the supply chain, which are estimated to cost around Rs. 20 billion. This accounts for 30-40% of the total agri-food production in the country.One of the key causes of this is the lack of integration between supply and demand . For instance, farmers cultivate their lands without having a scientific understanding of future needs and in the absence of a national-level cultivation strategy to fulfill local demand. This leads to an overproduction of certain crops, which ultimately results in considerable losses for farmers.

Nevertheless, high food miles set along the supply chain also causes a high degree of inefficiency. For instance, when commodities from different parts of the country reach the main economic centers , only to be redistributed, it can cause high cost and further damage to the produce. Also maladaptation of post harvest handling practices at various stages of the supply chain further lead to high wastage and inefficiencies.

Apart from that, a number of additional factors (eg: information asymmetry, limited supply of inputs, lack of infrastructure and support facilities, poor agricultural policies, import restrictions, and price controls, etc.) also hinder the smooth operation of supply chains. Finally, these can lead to significant pricing disparities of the commodities across the island.

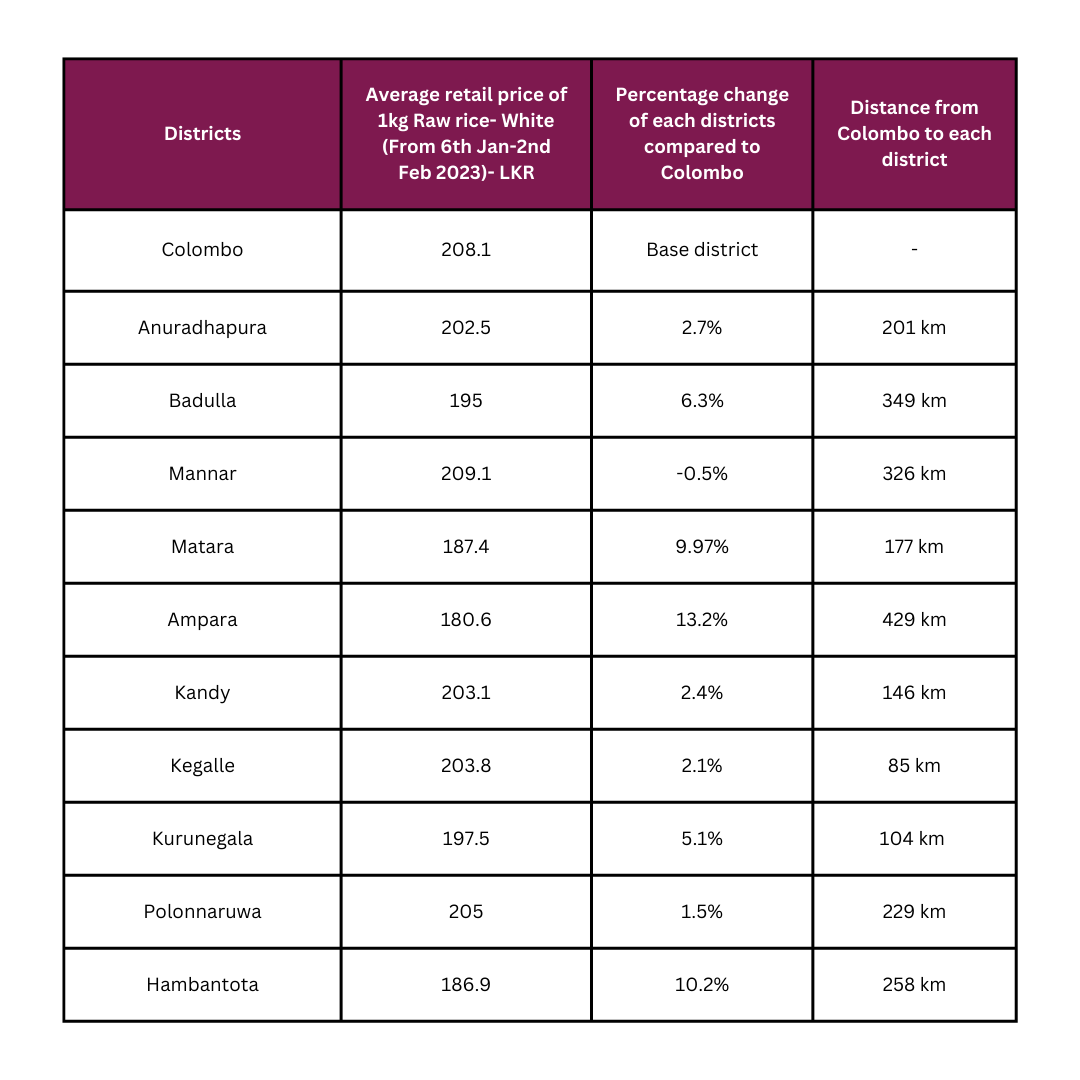

Source: Weekly prices, Hector Kobbekaduwa Research & Training Institute

In order to analyze the pricing disparities of Raw Rice (white) across the island, the average of weekly prices were obtained from the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute for four weeks from 6th of January 2023 to 2nd of February 2023 of 10 districts across Sri Lanka. Colombo was taken as the base district and the percentage changes were calculated to identify whether there is a significant difference in the prices of each district against Colombo.

Due to lower average retail pricing than Colombo's average retail price, it can be seen from the calculations that in certain paddy production areas like Ampara, Hambantota, and Matara have greater percentage changes of 13.2%, 10.2%, and 9.97% against Colombo respectively. In comparison to Colombo; Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, and Kurunegala also have relatively lower average retail prices. The common reason behind this is that food supply to Colombo varies between types of commodities and does not depend on the closest production areas. The variations in distance and transport costs are reflected in the price disparities in Colombo. Apart from that, some other reasons for the price disparities across the island could be possibly due to complex interactions between supply and demand, income variation, uneven population distribution, price controls and the price of close substitutes.

Way forward

In light of the aforementioned issues, continuous development and tailor made policies should be introduced to establish a more resilient agri-food supply chain. Hence below are a few recommendations that can be introduced to the system.

Establish post harvest handling hubs across main cities of the island to improve the efficiency of the sector

Farmers/ supply chain actors to be more vigilant on proper post harvest handling techniques to minimize losses

Utilize railway system as a cost effective source of transportation

Promote the use of digital marketing platforms to connect different actors across the supply chain

Integrate these platforms with financial services such as online payments, credit-based transactions, and loan facilities through banks

Enhance collaboration among different actors across the supply chain to reduce cost and increase efficiency (eg: promote forward and backward integration via business partnerships)

Encourage private sector participants to invest in modern technologies along the supply chain to reduce losses

Encourage innovations/processes that can improve the efficiency and reduce losses along the supply chain

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.