Originally appeared on Daily FT

By Dr. Roshan Perera

A budget sets out the government’s plan for the economy together with the financial resources required to achieve those plans. It also indicates the broad policy direction and priorities of the government. Any assessment of the Budget cannot be undertaken without an understanding of where the economy is right now. In other words, the Budget must be evaluated in the current economic context.

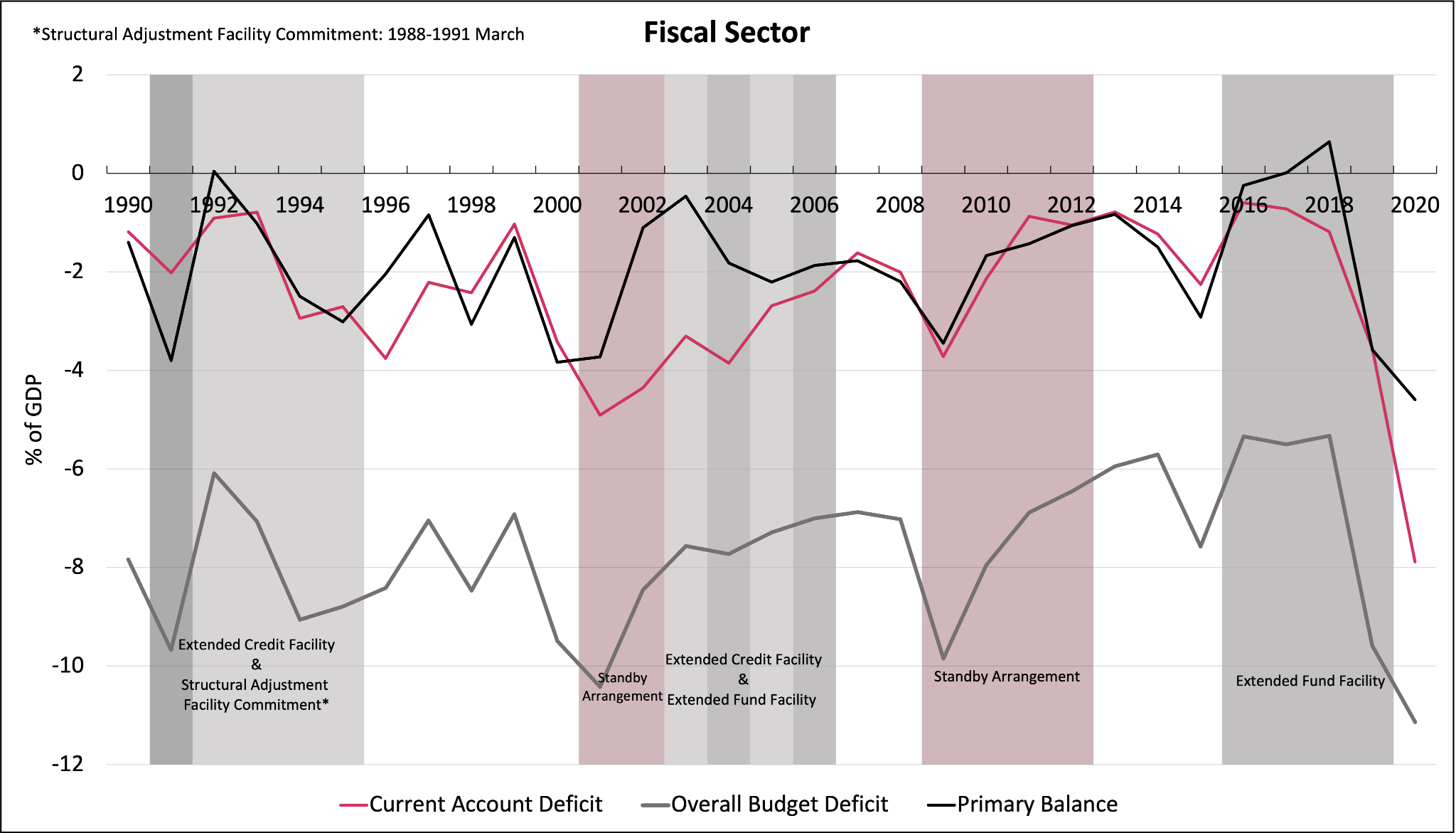

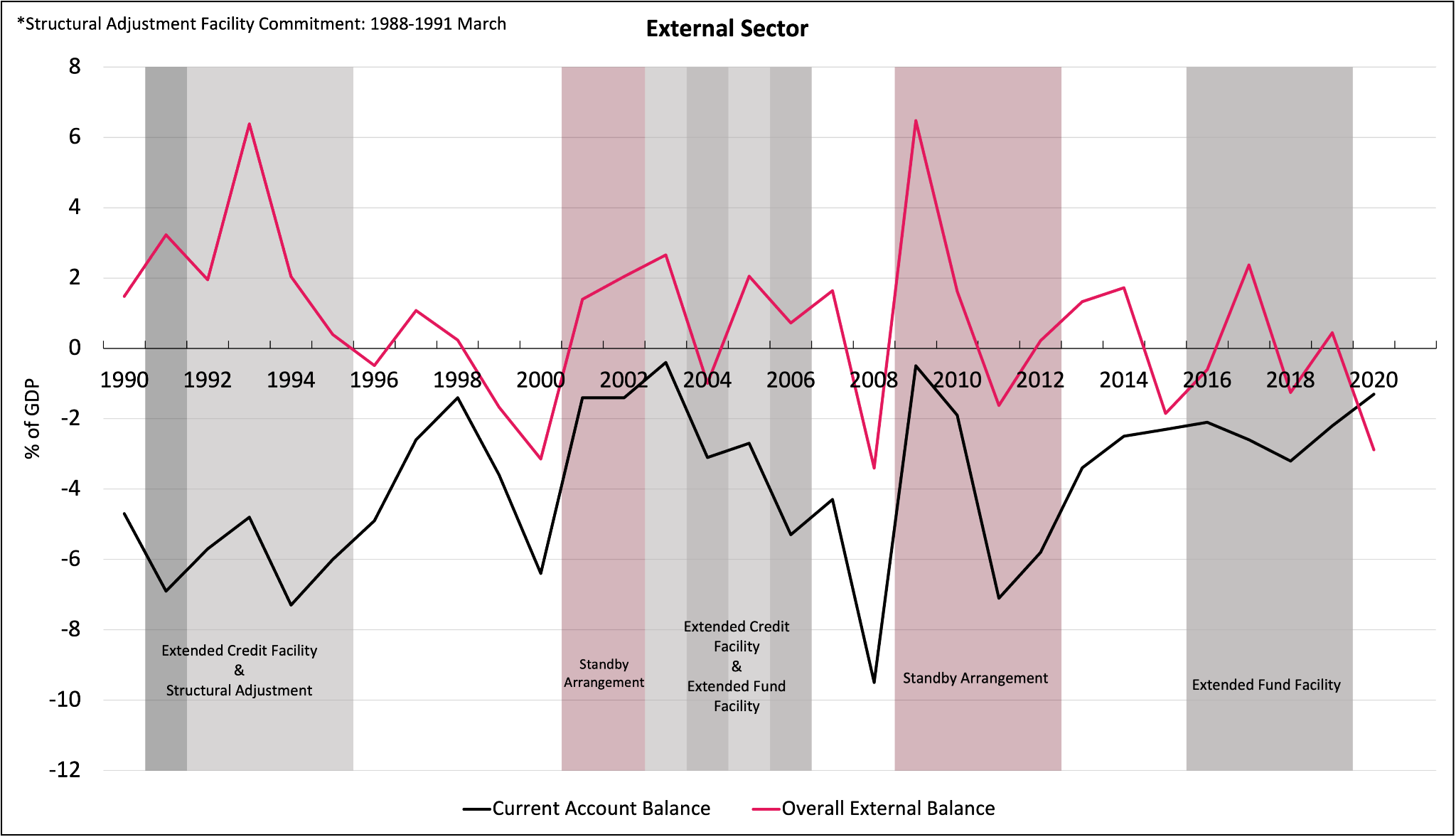

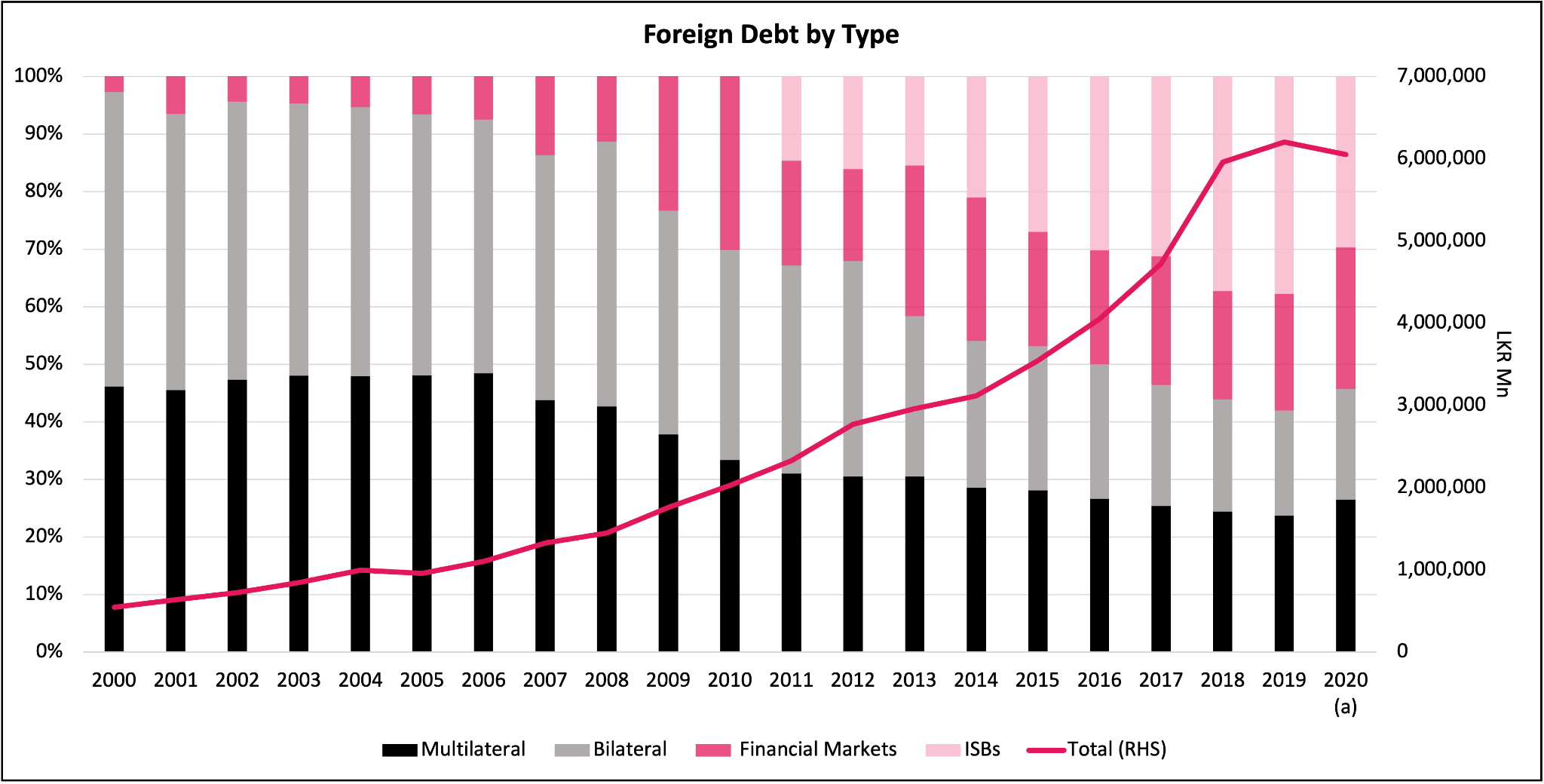

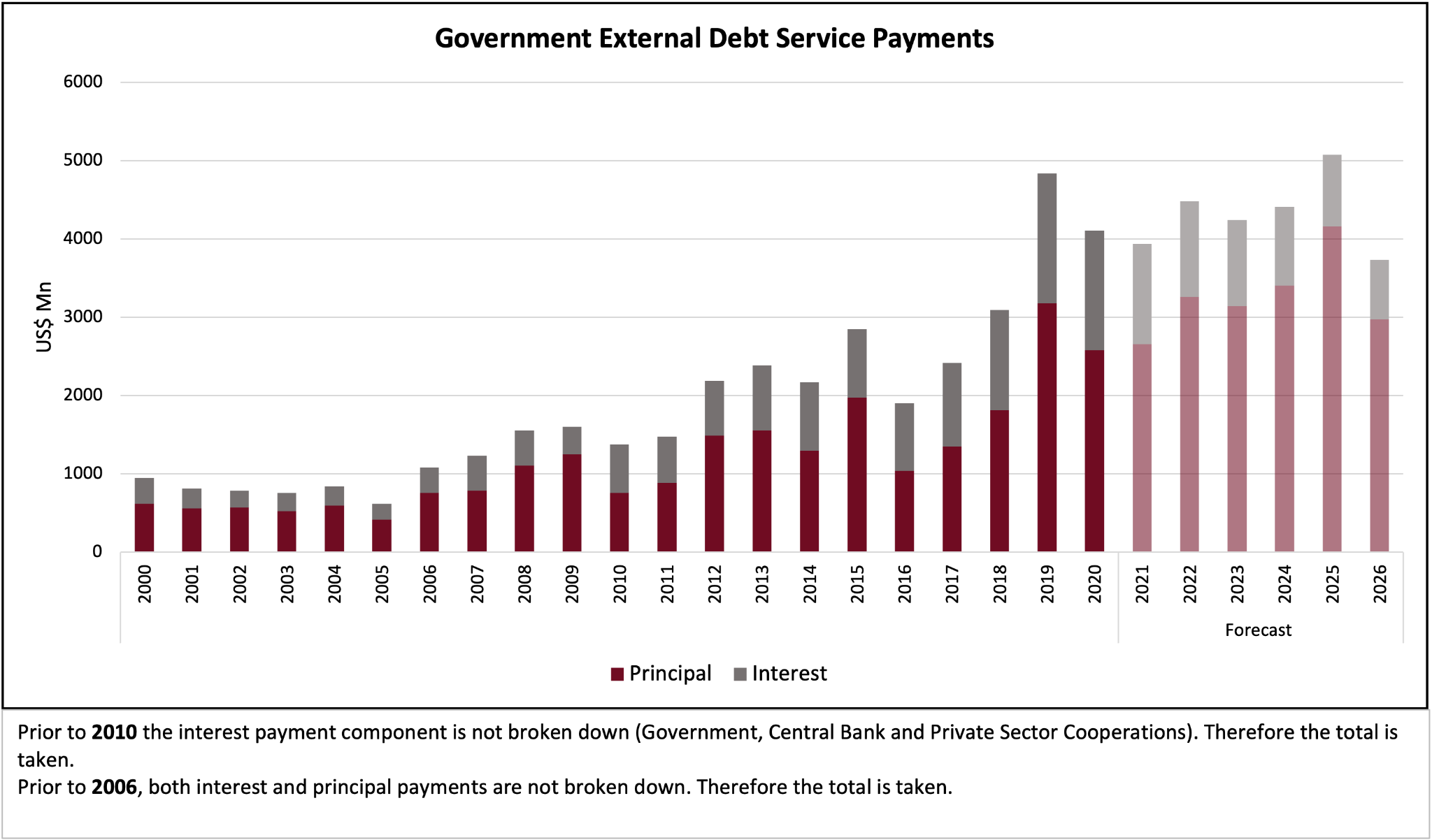

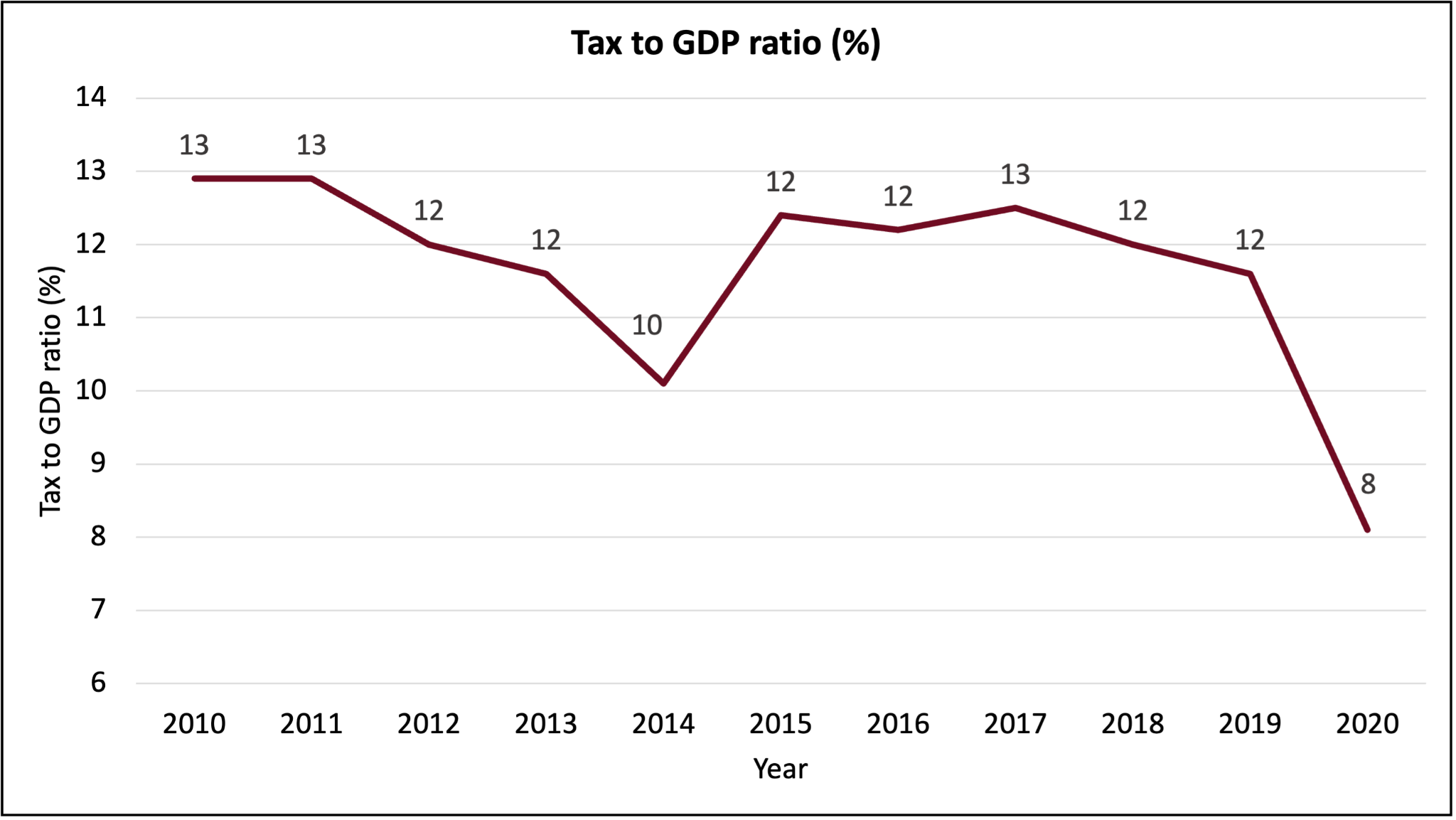

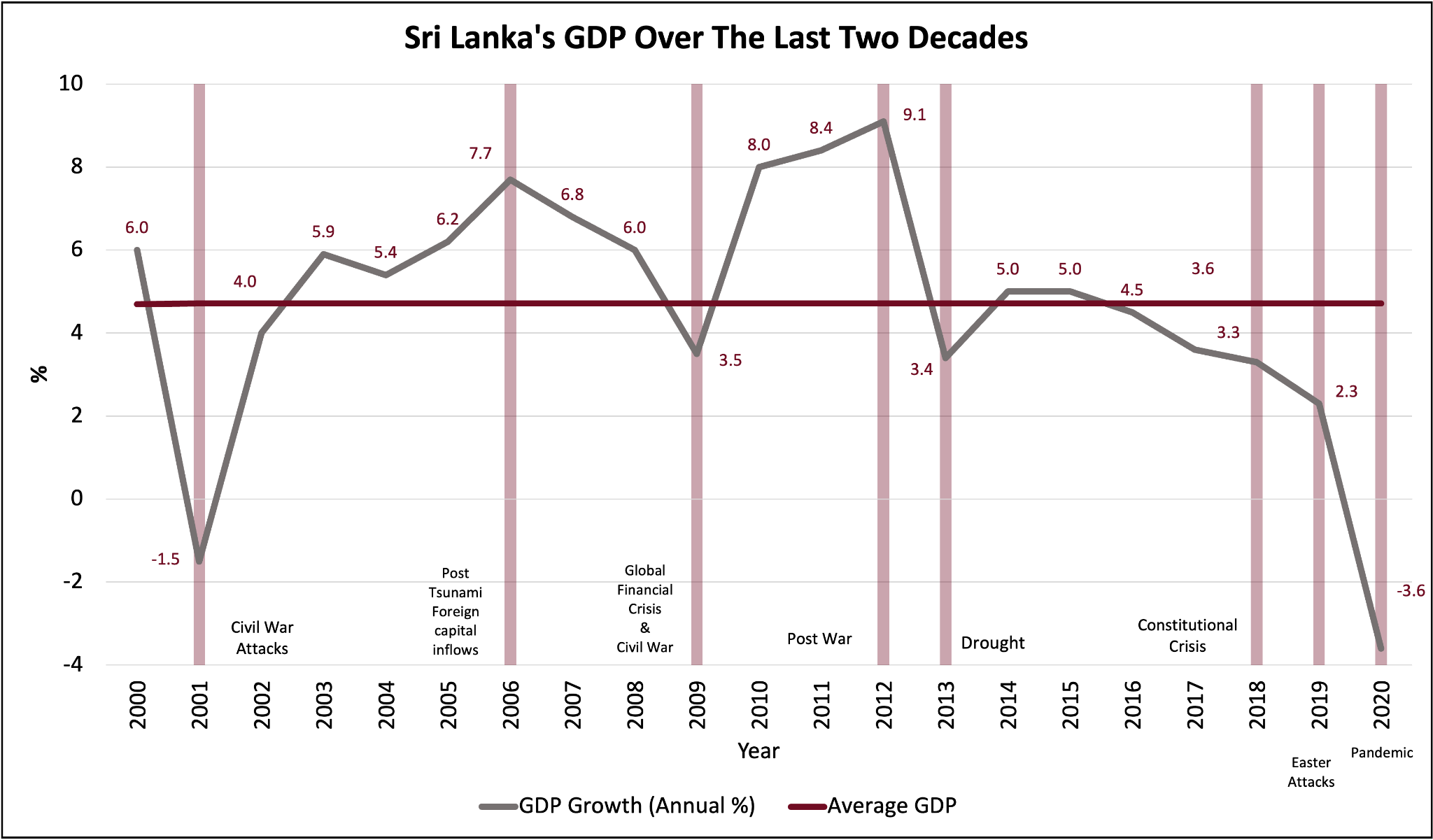

Looking at the key economic indicators, it is clear that the economy is at a critical juncture. The country suffered the sharpest decline in economic growth in 2020. Although growth is picking up, the economy is likely to remain below pre-pandemic levels. Inflation is rising due to external pressures from supply side disruptions and shortages in international markets. Domestically, financing of the Government’s budget through banking sources (Central Bank and commercial banks) is exerting upward pressure on prices. On the fiscal front, government revenue declined to historic lows due to the impact of sweeping tax policy changes as well as the slowdown in economic activity. Meanwhile, the Government has very little leeway on expenditure, as much of it goes to pay salaries of government servants and to make interest payments – all contractual obligations. The consequent widening fiscal deficit has been financed through increasing borrowings leading to higher debt levels and debt service payments. Downgrading of the sovereign by rating agencies has limited access to international capital markets, exacerbating issues in the macroeconomy. The current economic crisis is not due to the Covid-19 pandemic alone. Sri Lanka entered the pandemic with a slowing economy and a weak fiscal position; the result of years of poor economic policies undertaken by successive governments.

Budget 2022 was an opportunity for the country to reset and for the economy to move to a more sustainable growth path. With Sri Lanka losing access to capital markets and large debt service payments over the next few years, the urgent need was to restore fiscal credibility and strengthen market confidence. Because credibility of the fiscal strategy is vital for stabilising the macroeconomy and restoring the confidence of investors. Hence, the primary focus of the Budget 2022 should have been on correcting the twin deficits, i.e., the fiscal deficit and the external current account deficit, because of the spillover effects into the rest of the economy through interest rates and exchange rates.

According to the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework, the fiscal deficit is projected to decline to 8.8% in 2022 from 11.1% in 2021 (see Table 1 for details).

With minimal wiggle room on the expenditure front, the focus of fiscal consolidation is on revenue generation. Tax revenue is projected to increase by 50% in 2022 from the revised estimates for 2021. Given that actual revenue consistently falls short of estimates, how realistic these projections are is called into question. A major portion of the increase in tax collection in 2022 is expected from the introduction of several new taxes. In addition, the VAT rate on banks and financial service providers is proposed to be raised to 18% from 15% as a one-time increase. Collectively, these taxes are estimated to raise Rs. 304 billion, accounting for around 46% of the total projected increase in tax revenue in 2022 (See Table 2 for details).

As a comparison, the Interim Budget for 2015 introduced a super gains tax of 25% applicable on any company or individual with profits over Rs. 2 billion in the tax year 2013/14 as a one-off tax. The revenue collected from this tax was Rs. 50 billion. Furthermore, the social security contribution is similar to the Nation-Building Tax (NBT), which was a 2% tax on turnover imposed on entities with liable turnover in excess of Rs. 15 million per annum. In 2019, the NBT generated revenue of Rs. 70 billion before it was abolished in December 2019. With a higher turnover threshold and the current restrictions on imports, it will be challenging to raise the estimated revenue from the proposed social security contribution. In addition, the ability to raise the proposed revenue depends on how expeditiously required legislation can be presented to Parliament. Delays in passing legislation have hampered revenue collection in the past.

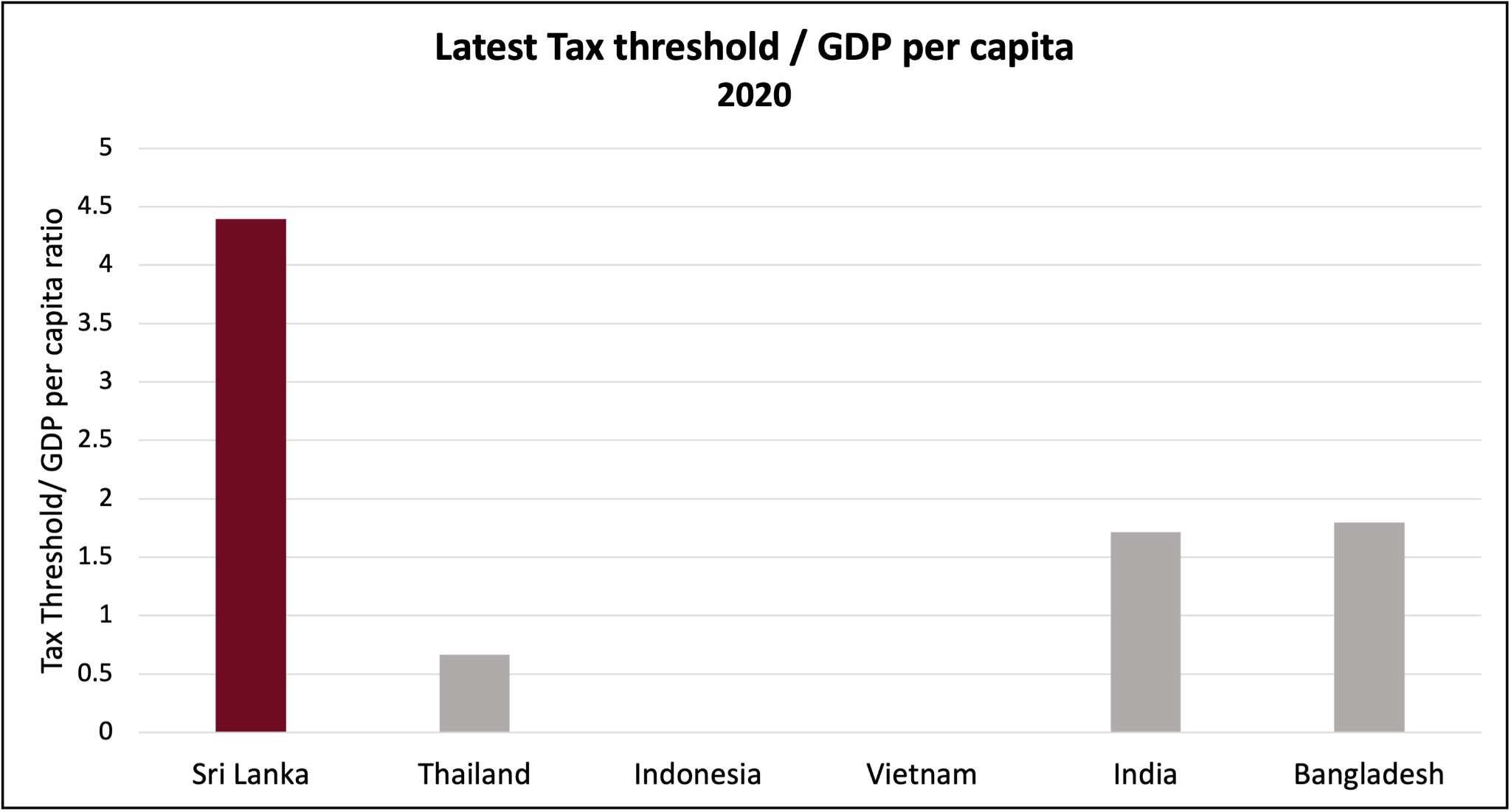

The question that needs to be asked is why introduce new taxes on a revenue administration that is already stretched when there is ample room to revise thresholds and rates on several existing taxes. This would have been much simpler to implement and would have required minimal amendments to existing legislation. In addition, taxes with retrospective effect, such as the surcharge tax, are not good signals for prospective investors.

The big question is whether the revenue estimates in Budget 2022 are based on reasonable projections. What if the proposed revenue collection does not materialise? Is there leeway to cut expenditure to match the revenue shortfall? If not, will this mean a widening budget deficit and additional borrowing? With minimal access to foreign financing sources, this will mean higher borrowing from domestic sources, particularly the banking sector. This will have economy-wide implications through higher domestic interest rates and crowding out resources from the private sector.

On the expenditure front, overall, there has not been a huge increase in total expenditure. However, the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Public Security account for around 12% of total expenditure, while spending on health and education accounts for 6% and 4%, respectively, of the total. In terms of the composition of expenditure, salaries and wages comprise 34% of recurrent expenditure while interest payments account for 37%. While the Government has limited room to cut expenditure, making permanent another 53,000 graduate trainees may not provide the best signal in terms of the Government’s commitment to reversing the fiscal situation. Furthermore, the Budget for 2022 has reduced the allocation for subsidies and transfers. An important lesson from the pandemic was the need to build buffers during good times to be able to assist vulnerable households and micro and small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) who were disproportionately affected. Although the Budget proposes a one-off cash transfer to selected groups such as MSME entrepreneurs, school bus and van drivers, three-wheel drivers, and private bus drivers who were affected by the lockdowns, it does not address informal workers in other sectors of the economy who account for around 60% of the total workforce. Ad hoc cash transfers are not sufficient to address these issues. A more comprehensive social protection scheme is required to prevent vulnerable groups from falling into poverty due to unexpected events.

Macroeconomic stability also requires external sector stability. Large foreign debt service payments and dwindling foreign reserves have led to import controls and a tight rein on foreign exchange market. But a more sustainable solution to the external crisis is to encourage exports. The Budget refers to transforming the economy into an advanced manufacturing economy and encouraging exports to earn foreign exchange. This requires addressing the structural weaknesses in the economy hindering competitiveness and productivity. In this light, the question to ask is if spending priorities and policy measures announced in Budget 2022 address these bottlenecks. The Budget has allocated Rs. 5 billion for infrastructure for new product investment zones. In addition, the Budget refers to “…a special focus on expanding the IT sector and promoting BPOs and…a techno-entrepreneurship-driven economy”. However, the allocation for digitalisation is less than Rs. 5 billion. This is in comparison to the allocation for highways of around Rs. 270 billion and rural development programmes (Gama Samaga Pilisandara) of around Rs. 85 billion.

(The writer is a Senior Research Fellow at the Advocata Institute and a former Director of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka)