Originally appeared on The Morning

By Anuka Ratnayake

There is much discussion on the precarious financial situation of the island’s National Carrier SriLankan Airlines. A month ago, Minister of Ports, Shipping, and Aviation Nimal Siripala de Silva revealed that “The only way to rescue the National Carrier is via urgent restructuring” [1].

The airline has racked up significant losses while its debt obligations have increased significantly with the depreciation of the currency. Getting rid of the airline will allow the Government to focus on its limited resources to strengthen social security nets and improve social infrastructure.

The argument regarding the airline has been muddied by emotion, for it is ultimately the people who pay for it and who have the right to ask if this is the best use of taxpayers’ money.

SriLankan Airlines’ Annual Report for 2020/’21 (latest available annual report) provides that the SriLankan Airlines Group recorded a loss of Rs. 49.7 billion. However, the Ministry of Finance in its latest Annual Report records that the loss (before tax) of SriLankan Airlines for the year 2021/’22 is Rs. 170.8 billion [2]. The accumulated loss amounts to Rs. 542.5 billion as at 31 March 2022. The National Carrier lost Rs. 248.4 billion in the first four months of 2022 due to the volatility in exchange rates [3].

The airline is in debt to the Bank of Ceylon and the People’s Bank to the tune of $ 380 million in 2022, while another $ 80 million loan has been obtained from the Bank of Ceylon by mortgaging shares of SriLankan Catering. The banks have extended support to the airline on the basis of letters of comfort issued by the Ministry of Finance.

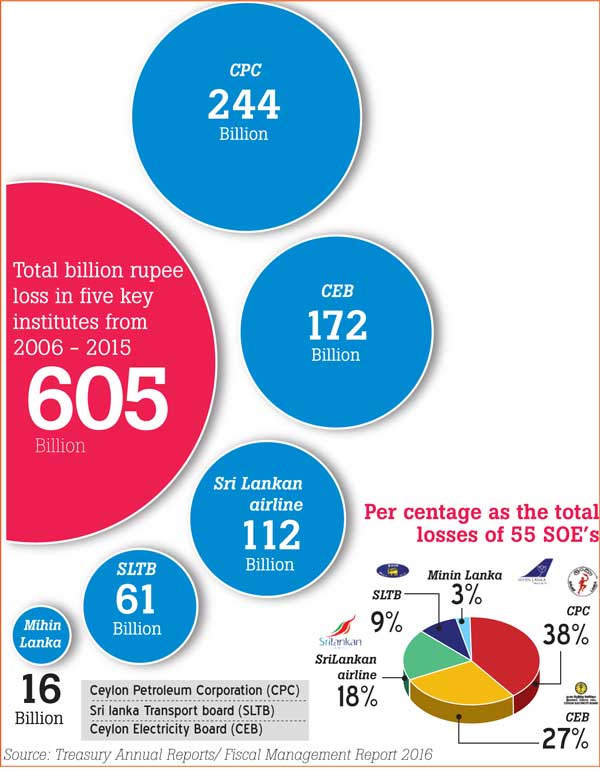

Further, the airline has a debt payable on an international bond on a Government guarantee of $ 175 million. The guarantees extended by the Government to banks and bondholders represent additional potential losses of public funds. The group owes an arrears amount of $ 325 million to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) such as the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), the Airport and Aviation Services (Sri Lanka) (AASL), and the Civil Aviation Authority of Sri Lanka (CAASL) [4].

The group’s current liabilities exceeded its current assets by Rs. 214.6 billion by 31 March 2021 and the total equity of the company as at reporting date has declined to a negative Rs. 281.5 billion.

The Auditor General’s report has continuously warned the company that “a material uncertainty exists that may cast significant doubt on the group’s ability to continue as a going concern” [5]. The Auditor General has relied on the Cabinet approval dated 7 February 2022 and the letter issued by the Secretary to the Treasury on 24 February 2022 confirming the support of the Government to the company to continue its operations as a “going concern”. In simpler terms, the SriLankan Airlines Group is technically insolvent and it continues to operate using taxpayer money.

The airline last reported a profit in 2008, under the management of Emirates. It has failed to report a profit in any year since then. The airline industry is known to be a high-risk, low profitability business.

Future losses and lessons learnt from India

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has now reached a Staff-Level Agreement (SLA) with Sri Lanka to assist its economic recovery process. It was agreed that the IMF would provide an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of $ 2.9 billion on a 48-month arrangement.

The total debt of SriLankan Airlines (just over $ 1 billion) is nearly one-third of the EFF. Sustaining further losses is an impossible task since the Government can no longer fund the airline. Covering future losses of the airline through tax increases is unacceptable given the dire economic conditions faced by the public.

Sri Lanka needs air connectivity, but this is best provided by privatising air services and not by operating an airline. A good example is the Air India privatisation which took place in the past year. The Indian National Carrier was sold to the Tata Group for the relatively small sum of INR 180 billion [6]. Prior to the sale of the airline, it was losing $ 3 million a day on average, which totaled to over $ 1 billion per year [7].

The rising aviation fuel prices and airport usage charges were not sustainable after the pandemic restricted air travel. Further, competition from low-cost carriers and the poor financial performance of the airline made things worse. Air India’s poor client orientation, lack of punctuality, obsolete productivity practises, and poor revenue generation techniques were among the reasons for its incompetency [8].

The impact of the Air India privatisation was discussed at a panel at the ReformNow Conference hosted by the Advocata Institute. The panellists stressed how the Tata Group had already begun the process of value addition through efficient customer care services, improving fleet productivity, and focusing on budget flights for the domestic market.

Aviation hub

Singapore’s aviation policy has been a key factor in the growth of Singapore’s Changi International Airport, where air transport contributed to nearly $ 20 billion of value added to the Singapore economy or about 6% of the Singapore GDP in 2011.

There is much public support for restructuring SriLankan Airlines due to its heavy burden on State coffers and thereby the taxpayers. However, rather than selling the airline alone, bundling the sale of the airline with the other business units such as SriLankan Catering and SriLankan Airlines Ground Handling would be attractive to investors. At the same time, the airport too can be included and marketed as an aviation package with a similar potential to the Changi International Airport.

A national carrier is a source of pride, but it is not a priority for a cash-strapped Government. The airline should be disposed of or even closed, and a liberal air services policy should be adopted instead.

This could boost growth and truly turn Sri Lanka into an aviation hub, freeing taxpayers’ money to be used for health, education, and other priorities.

References

1. https://www.ft.lk/top-story/Answering-aviation-Aragalaya/26-739243

2. https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/a7a35d1a-556f-49b2-81e0-20294eb5a519

3. https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/bc1e8eaf-91eb-4cb3-94e0-35d81f65a949

4. https://www.ft.lk/top-story/Answering-aviation-Aragalaya/26-739243

5. https://www.srilankan.com/pdf/annual-report/SriLankan_Airlines_Annual_Report_2020-21_English.pdf

6. https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/explained-air-india-handover-government-to-tata-group-changes-1904217-2022-01-25

7. https://www.advocata.org/commentary-archives/2021/10/11/air-india-sold-privatise-srilankan-now

8. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-60150531

Anuka Ratnayake is a Research Assistant at the Advocata Institute. She can be contacted at anuka.advocata@gmail.com. The Advocata Institute is an Independent Public Policy Think Tank. The opinions expressed are the authors’ own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute.