Razeen Sally is Associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the Notional University of Singapore. He is Chairman of the Institute of Policy Studies, the main economic-policy think tank in his native Sri Lanka. Previously he taught at the London School of Economics, where he received his PhD. He has been Director of the European Centre for International Political Economy, a global-economy think tank in Brussels. He has held visiting research and teaching positions at Institut D’Etudes Politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris,

Australian National University, University of Hong Kong, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore and Dartmouth College in the USA. He was also Chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council on Competitiveness. He is an Adjunct Scholar at the Coto Institute and is on the advisory boards of the Institute of Economic Affairs (UK) and Centre for Independent Studies (Australia).

He is a member of the Mont Pelerin Society. Sally’s research and teaching focuses on global trade policy and Asia in the world economy. He has written on the WTD, FTAs and on different aspects of trade policy in Asia. He has also written on the history of economic ideas, especially the theory of commercial policy. His new book on Sri Lanka will be published in 2017

Razeen Sally, a Professor at the National University of Singapore, shared his experience about the experience of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in South Asia and East Asia with Advocata, a Colombobased think tank promoting free market. While privatization is the best option to reduce the burden of state enterprises on society and improve t h e i r p e r f o r m a n c e , s u b j e c t i n g them t o competition, shielding them from politicization can also give benefits, he says in this interview.

There seems to have been an epidemic of state enterprises after World War II, especially in newly independent countries like Sri Lanka. When did state enterprises start to emerge in the world and in Sri Lanka? What is the historical background to SOEs?

In Sri Lanka as in India, many state enterprises date back to mid-1950s when the government policies took a turn towards to more intervention, more protection and using the state to promote investments in heavy industry and other areas. In this respect, the S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike government was following what the Nehru government was doing in India. So, the SOEs were intended to be the spearhead of economic development. And of course in Sri Lanka, this was really ratcheted up under Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government in 1970, when the state intended to take control of the commanding heights of the economy.

What were the intentions of the architects of SOEs? Have these objectives been met?

The answer is clearly no. The idea was to use the SOEs as part of an alternative model of economic development.

The model people had in mind was Soviet Union and its five-year plan. And here there is a contrast with what was done in the East Asian countries and what was done in South Asia. South Asia went for heavy state-led investment, nationalisation, for various government internal controls and external protection - import substitution. And this model clearly failed, which led to later market reforms, from 1977 in Sri Lanka and from 1991 in India.

The East Asian countries - some of them actually had SOEs - like Taiwan. But on the whole they didn’t nationalise rampantly and they relied much more on the private sector to be the engine of economic development. It was part of a different model which was more open to international trade, which had fewer domestic controls, which had macroeconomic stability and so on.

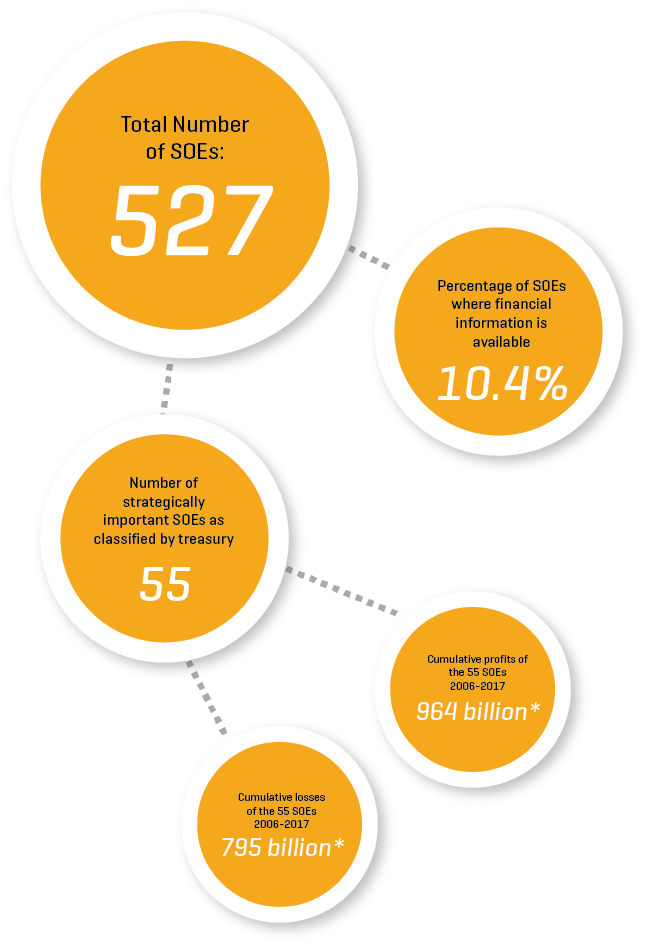

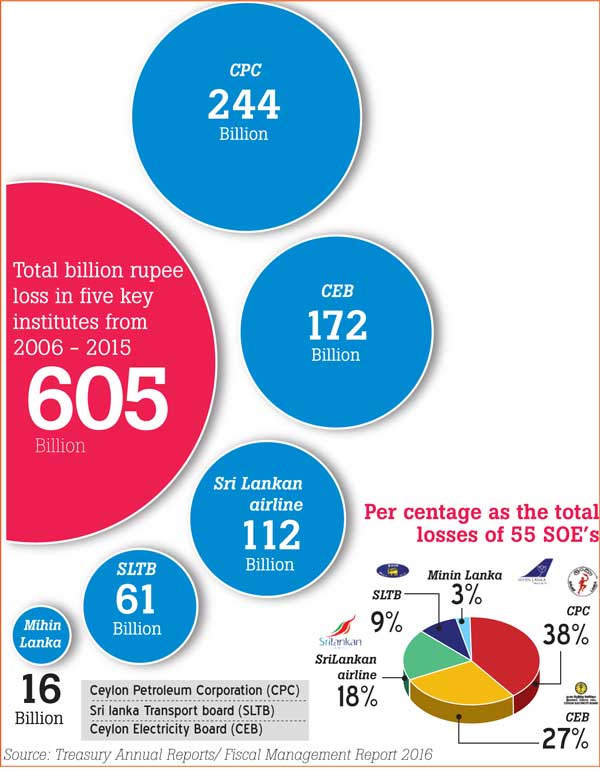

I would argue that the old model, which had nationalisation and SOEs controlling significant parts of the economy, definitely failed. And you see the costs of failure of SOEs in Sri Lanka. There are 250 or more SOEs, some that are hugely loss-making, that are a drain on an already depleted exchequer, that are heavily politicised, that crowd out private investment and that constrain consumer choice. So, it is a bad deal all around.

Why do so many state enterprises get into trouble and end up becoming burdens on the tax payer? Is there an inherent problem in the incentives or structure behind the SOEs that leads them on this path?

the world, state enterprises fail because there are disincentives to competition.

They are shielded from competition. They have a close link to the state. They are highly politicized. Appointments are not made on merit. The market is rigged in their favour, on prices and on production. Often they are protective from international competition as well as domestic competition. For all those reasons they fail.

And they are a drag on the economy, on the exchequer and on consumers - they limit competition. There are of course, exceptions.

One can point to a minority of SOEs in a few countries in the world that have not prevented fast and successful economic development. One thinks in particular of the government-linked companies (GLCs) in Singapore. Singapore, which is a fantastic and successful economy, still has large companies that are majority state-owned, that are grouped under Temasek - the state holding company - and are commercially viable. Some of them have done very well competing internationally. Singapore Airlines is perhaps the best example.

That they have been subjected to competition is the basic answer - and in a small economy like Singapore, which is highly open to the world. It is the most open economy of any size in the world with trade at close to 400 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

The GLCs that play in the international market place are subject to fierce international competition in the market place. That’s true of Singapore Airlines, that’s true of the port services authority and that’s true of state-owned banks and so on. Over the decades the government has put in place the mechanisms to separate ownership - that is to say by the state - from the management, of commercial enterprises. In other words, they’ve been depoliticised to a large extent. It would be wrong to say that all SOEs in all countries have failed.

That’s not true. For the most part it is true. But a handful of exceptions are there. Singapore is the one that really stands out for exceptional pieces. But it’s very difficult to try and replicate in a country like Sri Lanka, what Singapore has done - in a country where politics is much more extrusive, where it is much more difficult to depoliticise the running of SOEs and also much more difficult to subject them to competition from domestic players and also from international players. Malaysia has a holding company called Khazanah, which is similar in some ways to Temasek in Singapore.

This holding company houses a number of leading SOEs in Malaysia, which accounts for about one third of Malaysian output. At least one of them is a big player in Sri Lanka. The Malaysian GLCs don’t perform nearly as well as Singapore GLCs - for two reasons. Firstly, they are less subject to competition and secondly, they are much more politicized. However, some of them are actually not too bad or are reasonably good because they have been shielded more than the others from politics.

What can be done?

The first best solution to the running of SOEs in Sri Lanka is to have a timetable to privatise. So yes, would use the ‘P’ word without feeling embarrassed about it. The obvious economically efficient solution is to privatize as many of the SOEs as possible over a realistic period of time. We know that politically this is not on the cards at the moment.

So the ‘P’ word is not used. As a matter of expediency that’s understandable. But I think as a medium to long-term objective, privatisation should be the way to go. However, now we have to get the second-best scenarios and second-best solutions. If large-scale privatisation is not feasible, what can be done in the short term, over the next one or two parliamentary terms, to improve the current dismal situation of the SOEs that won’t be as good as and as efficient as full privatisation, but might deliver a better result than what we have at the moment?’ In other words, improve the running of the enterprises; make them more commercially viable, more productive. In this scenario, we have to look at the other countries that have better practices. So Singapore comes to mind and so does Malaysia.

So we should look at the Temasek and Khazanah models of having a state holding company for SOEs. The lesson I would draw from the best example, which is Temasek, is that first you subject them to all-round competition, including international competition. And second, you put in place mechanism to depoliticise them as much as possible. In other words, separate ownership from management.

That’s the starting point. Then we can ask ourselves, ‘What should be the criteria for making these principles real?’ I was at a conference in Goa to discuss Indian reforms and I was part of a group that looked at this Temasek - Khazanah type of a model. And the local participants were interested in what lessons could there be for India, which is also not in the game of big privatisations.

As a first step, there is no point setting up a state-owned holding company and calling it something that’s done on the Temasek or Khazanah model if you’re not going to change the current operating procedures. So, the point is to have serious reforms, even if you can’t do privatisation. So what can you do? Firstly, identify the enterprises that essentially operate in a commercial sphere, where there is some competition already or where there could be more competition. If you have a state-run monopoly or oligopoly, then don’t put it in such a holding company.

Keep it separate. Because that’s probably going to be more politicized anyway there may be other public policy objectives that will get involved in the running of that enterprise. So keep that to one side. Rather, put in this basket enterprises that are commercial. So, that would include SriLankan Airlines, Mihin Air and the Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB) but not the Ceylon Electricity Board. So, in other words, don’t put all SOEs in this holding company, only put some of them that operate in a commercial sphere.

These should be corporatised with initially majority state’s ownership. Then you should start introducing the minority equity participation. And Temasek is interesting because, in the key enterprises, the government still retains the majority equity, therefore control. But they have actually gradually beefed up the minority equity in most of the Temasek enterprises.

That’s also a boost for the stock exchange or financial markets. And in some cases with nonpriority enterprises, they have actually taken the private sector stakes to a majority of equity and the government has retained only a minority of equity - and in some cases actually exited altogether. But in the meantime, the government could be with the minority equity - up to 19 percent. Maybe when the time is right politically, move into the majority private ownership. But the holding company should include airlines, buses, telcos and whatever is commercially viable and subject to competition.

We talk of loss-making state enterprises hurting the people. Are there other fallouts of badly managed SOEs? What’s a reasonable way of counting the total costs of SOEs on the economy?

Losses are the tip of the iceberg. And of course there are other SOEs in other countries that are hugely profitable. But that’s not an indication of overall economic efficiency. They are profitable because they have monopoly rents. They are not subject to normal competition.

So, I think the cost of SOEs that operate in rigged markets is the costs that fall on the consumer because of lack of competition. These might be difficult to quantify. We are talking of usually higher than normal prices, restricted product variety, often restricted supply of the product or service in question. I think probably the biggest losses to the economy are the losses that come from lack of competition.

When the Public Utilities Commission was set up here by Prof. Rohan Samarajiva, the law provided that you cannot replace the entire board in one go. Two or few members can be appointed for one year. What is your opinion on a procedure of that nature?

You could try to introduce independent directors. Having independent anybody in Sri Lanka is very difficult at the moment. Some of the Temasek companies have had foreign CEOs. Mind you SriLankan had a foreign CEO when it tied up with Emirates. What happened to him? You could try to maybe have a regulation that there should be a minimum number of independently appointed directors to the boards of these companies and to the boards of the holding company as well. So, the government appointees would be restricted to a certain number and there would be some mechanism to appoint some of the rest.

But of course they would have to be qualified. There is no point appointing a lawyer who leads someone’s political campaign without prior commercial experience to be an independent director of a commercial enterprise. That’s one thing to play around with that.

We have seen companies like Temasek advertise globally. So do you suggest that some people could also be hired globally?

Yes. Target the diaspora as well. See whether you could attract some of the qualified people from the diaspora to be directors of these companies, CEOs or the senior management.