In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

As Sri Lankans, we are conditioned to have 4 priorities in life:

Get a degree

Build a house

Buy a car

Be a good citizen.

While this is the mantra of every teacher and every parent, the system in which we live and work in is filled with barriers. Let’s take the first goal for example. Before you get a degree, the first step is getting into school. Entering grade 1 is a painful and tedious process and even if you succeed, only about 7% [1] of school leavers will have the opportunity to enter a state university. What happens to the remaining 93%? The rest are dependent on external degrees, vocational training and private education institutes for their tertiary education.

Every dream we are conditioned to hustle for does not come easy. What is truly terrible is that the system also prevents you from realising your dream through hard work. Let’s analyse the case of owning a house.

Is the dream of owning your own home a realistic one?

I recall a recent conversation with my retired parents. “After pouring all of our EPF/ ETF, gratuity and housing loans and spending every cent kept we had saved for medical treatments, we still could not finish the ceiling and the light fittings of this house”.

My parents’ house was hardly anything fancy. It was a simple, single story, 1500 sq ft structure with basic amenities. This is the most common form of most Sri Lankan houses, even after pouring years of money and energy into building them.

The statistics by the Ministry of Housing and Construction [2] shows that more than 250,000 families live in temporary houses and more than 400,000 families live in houses with roofs with galvanized sheets. Another 386,000 families live in partly constructed houses; either the floor is not cemented, or the walls are not plastered. Isn’t it a very poor performance for a country categorized as Upper Middle Income by the World Bank?

Why is this so challenging?

The challenges of building a house are numerous and varied, from settling land disputes to finding a good contractor, the list continues on. A major factor that is often not included in this list of woes are the taxes on building and construction material that results in exorbitant raw material prices. The prices of these items are high, but we rarely question why.

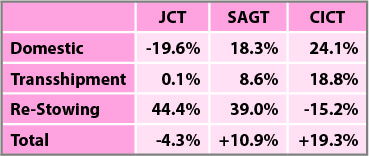

Here is a breakdown of border taxes of a few raw materials:

Wall tiles and floor tiles: 107%

Construction steel: 90%

Sanitary ware (Commodes, squatting pans): 62%

Graph by JB Securities

If you have ever attempted to build a 100 square foot basic toilet you may have realized how expensive material and labour can be. My focus is on basic sanitary facilities and not a 5-star grade bathroom with a bathtub and expensive fittings. How can a population afford to build a basic bathroom when their steel is taxed at 90% and their wall tiles and floor tiles are taxed at 107%?

The consequences of the tax create a chain reaction where individuals spend nearly two times greater than the actual price for steel in your basic construction. The reason why most of the houses are incomplete and most of the people becoming house builders for a lifetime is that they spend money for basics like steel, wall tiles and many other basic units double the actual cost and then inevitably run short on cash for the completion.

Why do these high taxes persist?

The purpose of high tariffs is to discourage the importation of construction material which is already available for a very reasonable price with higher quality in the global market. The excuse subsequent governments provide is that this is done to protect the local manufactures, but what is the rationale behind this kind of protectionism? Tariff protection is often provided for local manufactures, to give them breathing space in which to grow, and innovate up to the point that they catch up with global competition. However, this industry has been protected for a few decades and the lobbying gets stronger every year for more protectionism.

Is it fair to keep half of our population in temporary and incomplete houses as a result of tariff rates as high as 107% on basic material required for construction? Additionally, the purpose of this tax is to discourage some else who produces efficiently and effectively, in favour of more inefficient local production. In economic terms this is called a rent and the businesses who gain from this are the rent seekers – something Sri Lanka has many of. Most of the self-proclaimed successful businessmen are not the ones who have done better than the competition but have minted money from taxpayers by hiding behind government protectionism.

High taxes at what price?

The market contraction as a result of the unfair tariff policy goes beyond what can be seen at surface level. High taxes have an unseen dire impact on other supporting industries connected to construction. For instance, once you spend all your money for steel, tiles and electric materials you will be forced to cut your expenses on furniture, curtains, and other items which are also supplied by local businesses. Most Sri Lankans build a house on a housing loan. In addition to paying off a loan with interest, we also have to pay the rent of 107% on construction material - how justifiable is this?

This was simply a common man’s perspective. Even when considering industrial and commercial buildings, the situation is no different. For an instant if you are investing on a property in the leisure industry as a result of incurring a greater expense on construction material, one would have to consider the higher interest rates on loans and recovery of the capital. That higher recovery rate will create higher room rates, making the property almost uncompetitive in the market.

The dream of buying a car and dream of getting a degree is no different from building a house. Unfortunately, what former Indian president said about dreams is perfectly applicable to Sri Lankan’s dreams of building a house.

“Dream is not that which you see while sleeping it is something that does not let you sleep”. And yes, for the majority of Sri Lankans it’s a dream that doesn’t not let us sleep, keeping us up with worry till the last day and the last hour of our lives.

[1] University Grants Commission. 2018. Handbook of Statistics-2018. https://www.ugc.ac.lk/downloads/statistics/stat_2018/Chapter1.pdf

[2] Ministry of Housing and Construction, Housing Needs Assessment and Data Survey, 2016.

[3] Calculation by Advocata, using 2019 Tariff Guides