In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

Why should we have a limited government? – Part I

By Dilshani Ranawaka

“The government that governs best, governs least” – Thomas Jefferson

A state has three core tasks within a society: Protecting the life, liberty, and property of the people. As societies evolved, these core tasks were overlooked when more emphasis was given to managing economies. Should the state intervene in economic affairs? Would that be more beneficial to the economy and society?

For the following four weeks, “The coordination problem” will discuss why large governments cause more harm than good when they engage in tasks beyond ensuring freedom and security of the citizens and the rule of law.

The series titled “Why should we have a limited government?” will justify why large governments are a bane to the economy through arguments on costs, problems of coordination, and corruption. The series will then conclude with a fourth piece on what an ideal state looks like.

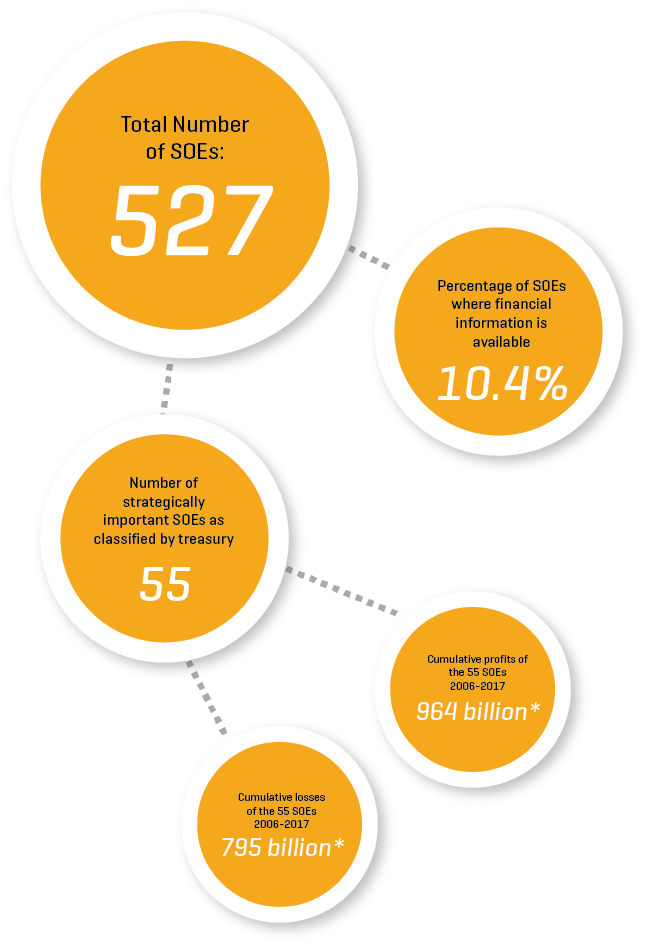

It is intuitive that larger governments incur larger costs. This takes place through two avenues: recurrent expenditures and management expenditures. The present Government has lost count of the number of enterprises the State owns, as revealed by the Advocata Institute’s recently published report “The State of State Enterprises in Sri Lanka – 2019”.

As of 2017, 1,389,767 of the labour force in Sri Lanka are employed in the public service. This is around 14.5% of the labour force. The enormity of these numbers is clear when compared with developed countries. For instance, Canada, which has a population of 37.6 million, has a public sector of 262,696, according to the official Government of Canada website, making it clear that a government does not need to be expansive even in the instance of a large population.

To make things even worse, the Government introduces salary increments either at the onset of an election or during a new budget proposal, instead of having increments dependent on performance.

With the recently proposed increment of Rs. 10,000 for the public sector, the expenditure for wages adds up to Rs. 768 billion for the year. This is around 25% of the government’s expenditure, as per the Budget in 2019. This exceeds the amount allocated for public investment (Rs. 756 billion) for the year 2019, which is around 24% of the budgeted expenditure for this year.

These complicated numbers bring questions to mind: Is providing jobs a role of a government? What is the opportunity cost? What are the indirect consequences? What is the concealed political gain from this process?

A state’s role goes beyond providing job opportunities. Some of the crucial elements a state should look into are national defence and maintaining law and order. The Easter attacks and ensuing events highlighted that the Government should be focusing more on its core functions before moving beyond.

Furthermore, when looking retrospectively at political campaigns, politicians target the votes of government officers mainly through the introduction of wage increments. While increments are positive incentives for productivity, politicians use them for popularity. In such cases, two factors increase the costs for the government. Since larger governments require more state officers for administration purposes, the costs incurred just for administration purposes increase. When politicians promising higher increments become popular, the cost burden for the government piles up.

Every decision made in the economy has an opportunity cost. A state could allocate resources either for consumption or for investments. Investments generate direct income in the long run while consumption creates effective demand which indirectly generates income. Given this backdrop, it is important to answer why unregulated and irresponsible expenditure by a state is catastrophic.

Let us explain through a simple example. If a household spends on consumption which does not generate income, the household has to resort to loans. A similar argument can be transposed towards a state. If a state spends on consumption (in this case the cost for expansion of the government), they have to utilise other methods such as loans or taxes which are reflected back on the taxpayers of the country. These wage expenditures incurred by the government are utilised for consumption most of the time. Alternatively, if politicians stop promising salary increments and reduce the size of the government, these wages could be utilised for public investments – a critical requirement for economic growth and long-term income generation.

Leaving vital services aside, what do state officers incur to the government? Losses or revenues? Would an additional state officer cover the cost of their wages and generate revenue through their productivity? Would it increase the efficiency of the department? These questions should be standard criteria before unnecessarily expanding particular state departments. The experience one has at most government institutions speaks for the inefficiency that plagues these institutions.

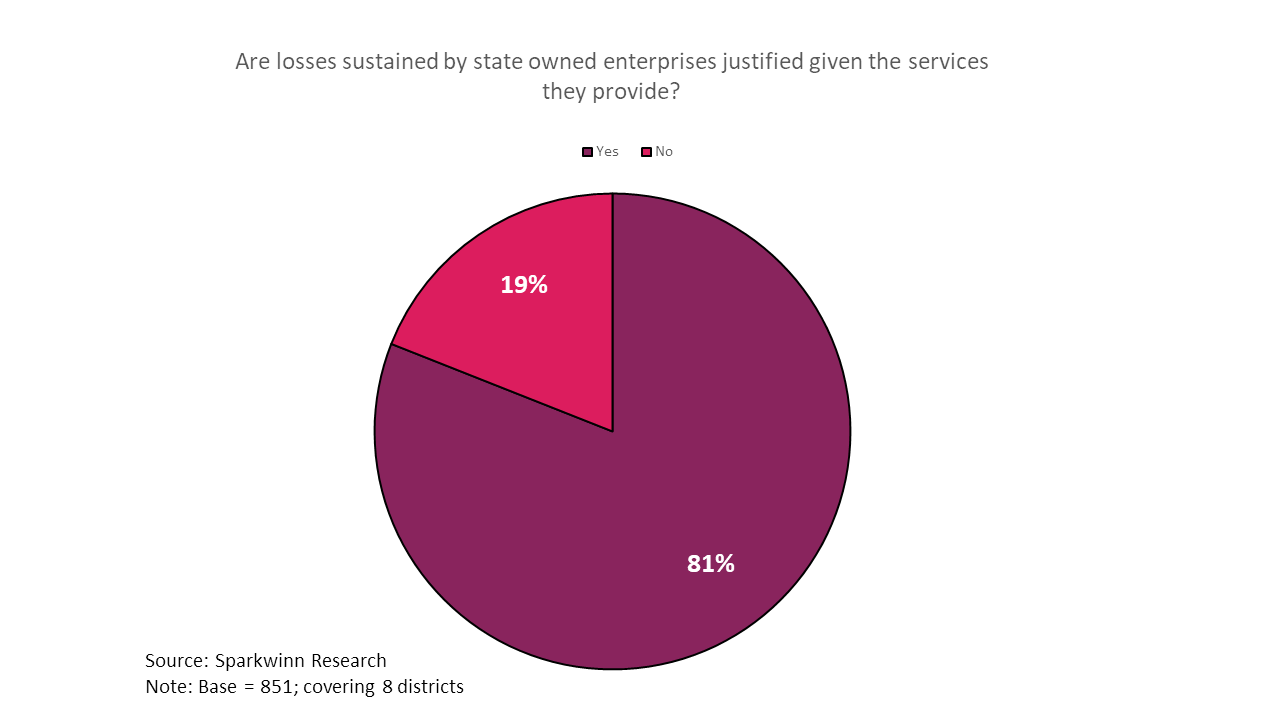

What is the underlying cause of incompetence of the State in Sri Lanka? If the government is supposed to facilitate services, why do they operate their entities in a manner they generate losses? Why do we constantly see power cuts through the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) if larger governments are meant to provide better services? Could we keep our trust on the State, given the way they function with our money?

Do larger governments function better? The evidence seems to indicate otherwise.