IMF Programme #17: takes two to tango

Originally appeared on the Daily FT, Ada derana, Groundviews

By Daniel Alphonsus

On Sri Lanka’s reform-regress-run to the IMF crisis cycle

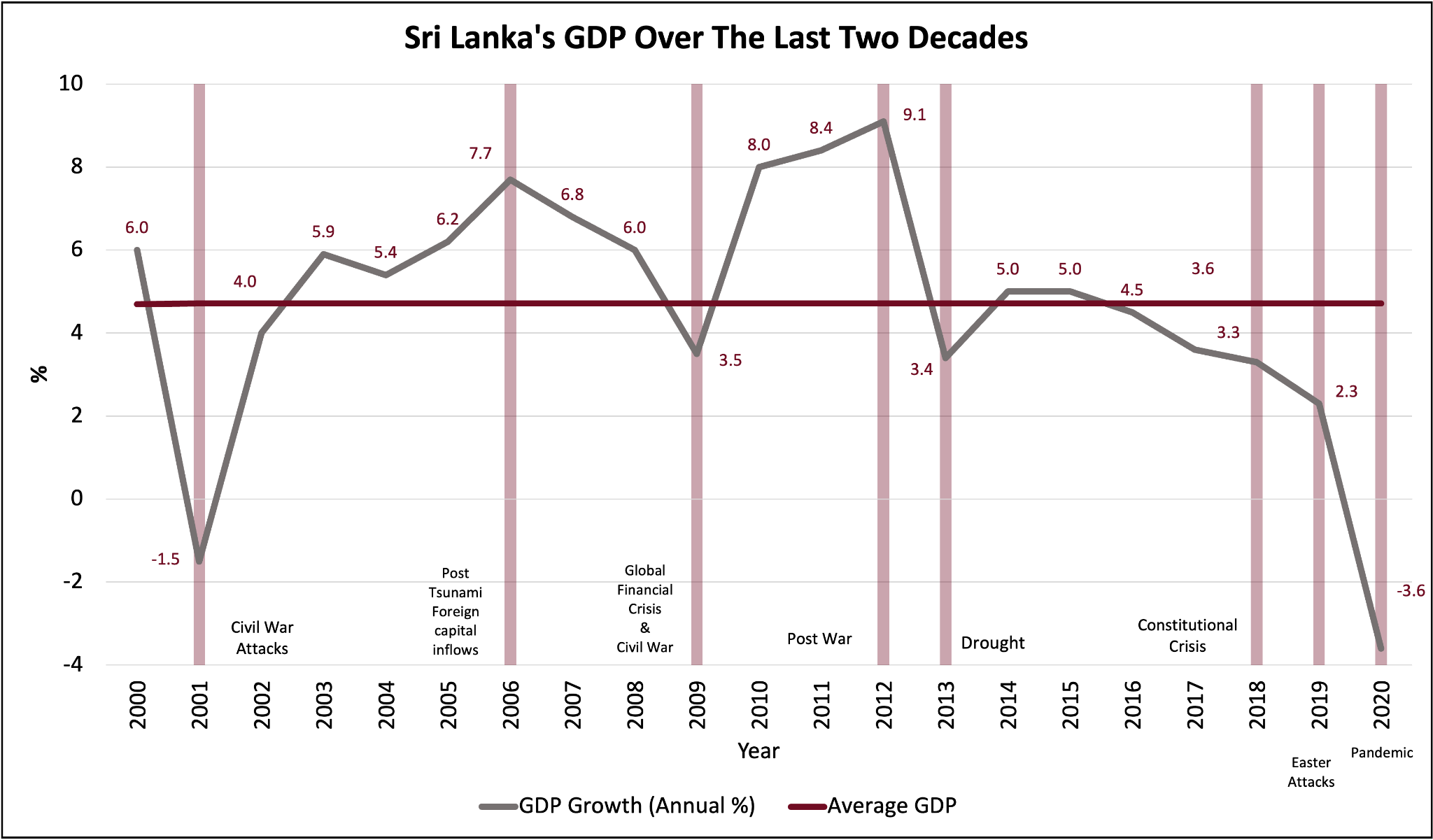

Countries never learn from others’ mistakes, they only learn from their own. Sri Lanka is an exception: we don’t even learn from our folly. Apparently neither does the IMF. Sri Lanka’s 17th IMF programme is set to be approved on March 20th. Is it welcome? Yes. Will it break Sri Lanka’s reform-regress-run to the IMF crisis cycle? Probably not.

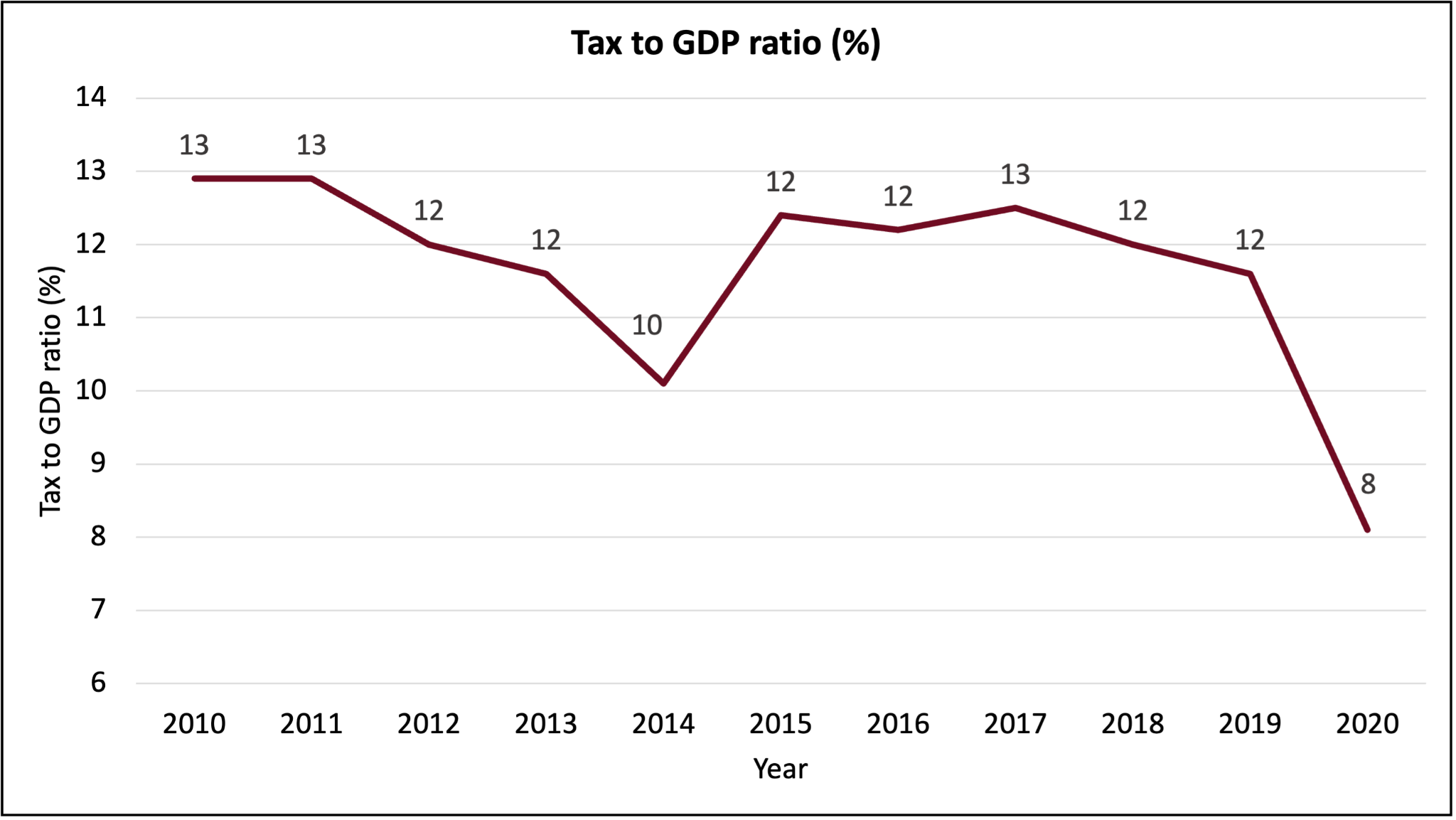

All reforms undertaken over the past half-year to win IMF board approval are reversible. None of them constitute entrenched changes in economic policy or governance. We are building our recovery on the shakiest of foundations. The fuel and electricity price ‘formulae’, tax plus interest rate increases and greater exchange rate flexibility can all be altered, more or less, at the stroke of a pen.

This is not surprising. Sri Lanka has a chequered history of cosmetic compliance: ticking the boxes of virtue and sensibility via international undertakings during desperate times, and then reverting to business-as-usual once crisis abates. We have good reason to think that, this time too, the future will rhyme with this past. Undoubtedly, post IMF board approval, some reforms less easy to rewind will come to pass - the new Central Bank Act being the most notable.

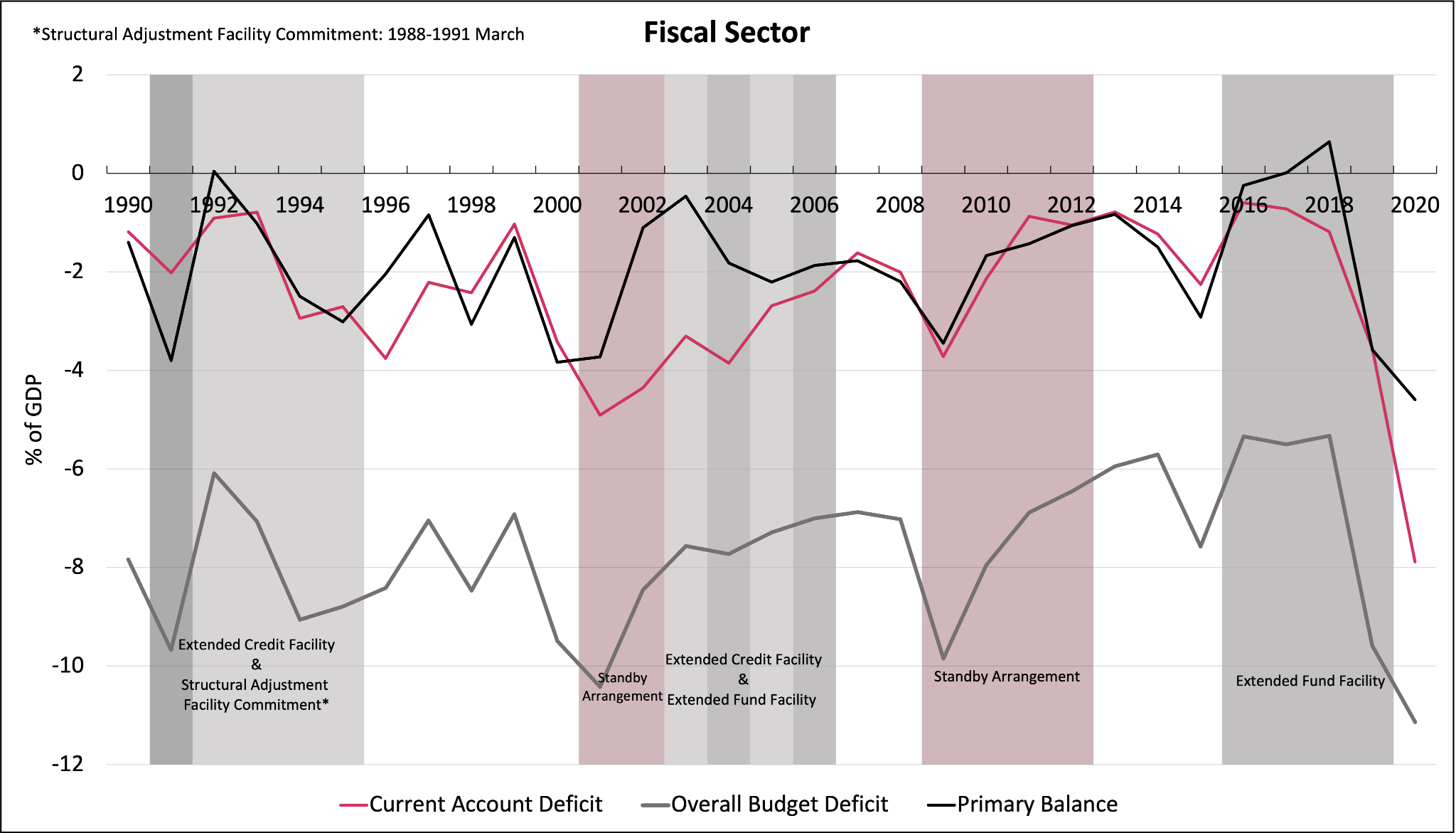

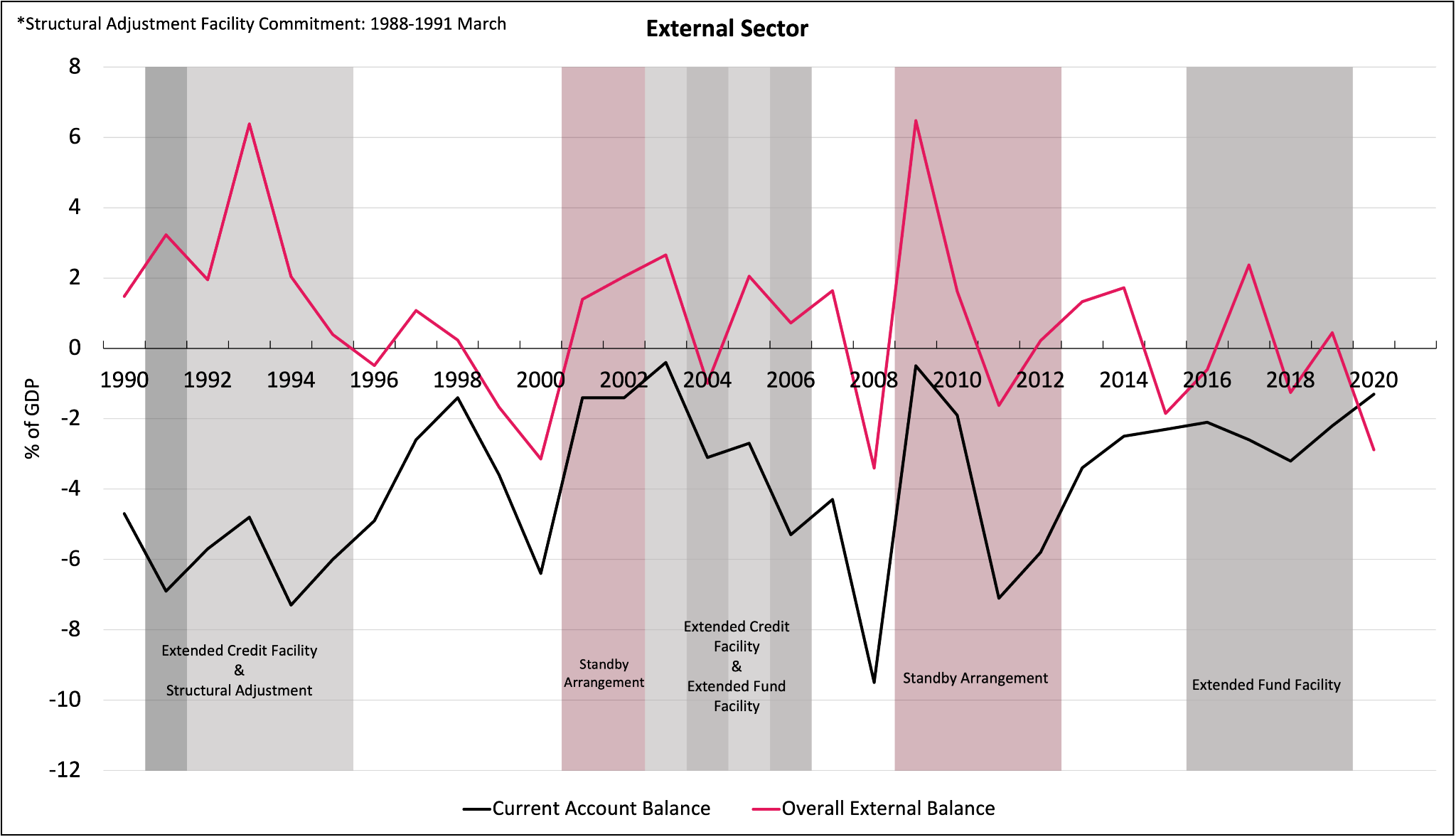

But the IMF’s bargaining power peaks prior to board approval. That is the decisive point in this process. It is the pivotal moment for any attempt to use this crisis to build the foundations required for breaking the crisis cycle and going from third-world to first. If the most contentious and critical reforms are not pushed through prior to board approval, there is good reason to think they will not come to pass. Remember that of its 16 programmes thus far, Sri Lanka’s has only completed two extended / structural programmes. The remainder are either relatively insignificant standby-facilities or derailed extended programmes

Considering the unprecedented nature of the current crisis, this is a colossal missed opportunity. As argued in a prequel article, Programme 17 could have and should have broken this cycle. Public opinion was desperate, the government commanded a super-majority in Parliament and the IMF held all the aces. The distinction between what is desirable and what is feasible had, almost overnight, dissolved. The cry for fuel and electricity was so piercing and loud that a comprehensive and deep programme permitting profound economic restructuring was possible for the first time since 1977.

Moreover, even if some of the required reforms come to fruition over Programme 17’s next few reviews - it will still be a missed opportunity. Reform takes time, effort and energy. These are scarce resources. As major structural reforms - such as the central bank act, fiscal rules, privatisations and labour market reforms - were not completed as prior actions, it means the first few reviews will be focussed on them. This will leave little room for some of the more complex long-term reforms; especially in land, the public service and regulatory policy (e.g. competition policy).

Of course, we are a sovereign state, so primary responsibility for this failure lies in our own polity. But we find little hope in ourselves. As weary and jaded citizens we tend to assume inertia, or worse, on our side as a given. Which is why this article is about the IMF’s failure.

What could the IMF had done differently? Especially considering its familiarity with Buenos Aires, it should know that it takes two to tango. As Keynes famously said of the IMF and World Bank; the Bank’s a fund, and the Fund’s a bank. Considering the creditor-borrower relationship between the IMF and Sri Lanka; as a creditor the IMF should bear some responsibility for the failure of so many programmes over such a long period of time. The IMF’s own kapuralas have conceived of programme conditionality as a form of collateral. The IMF ought demand more conditionality as collateral prior to lending. This, of course, requires review of past country programmes and, as we all know, economic history and country expertise are not exactly first-rank priorities at the Fund.

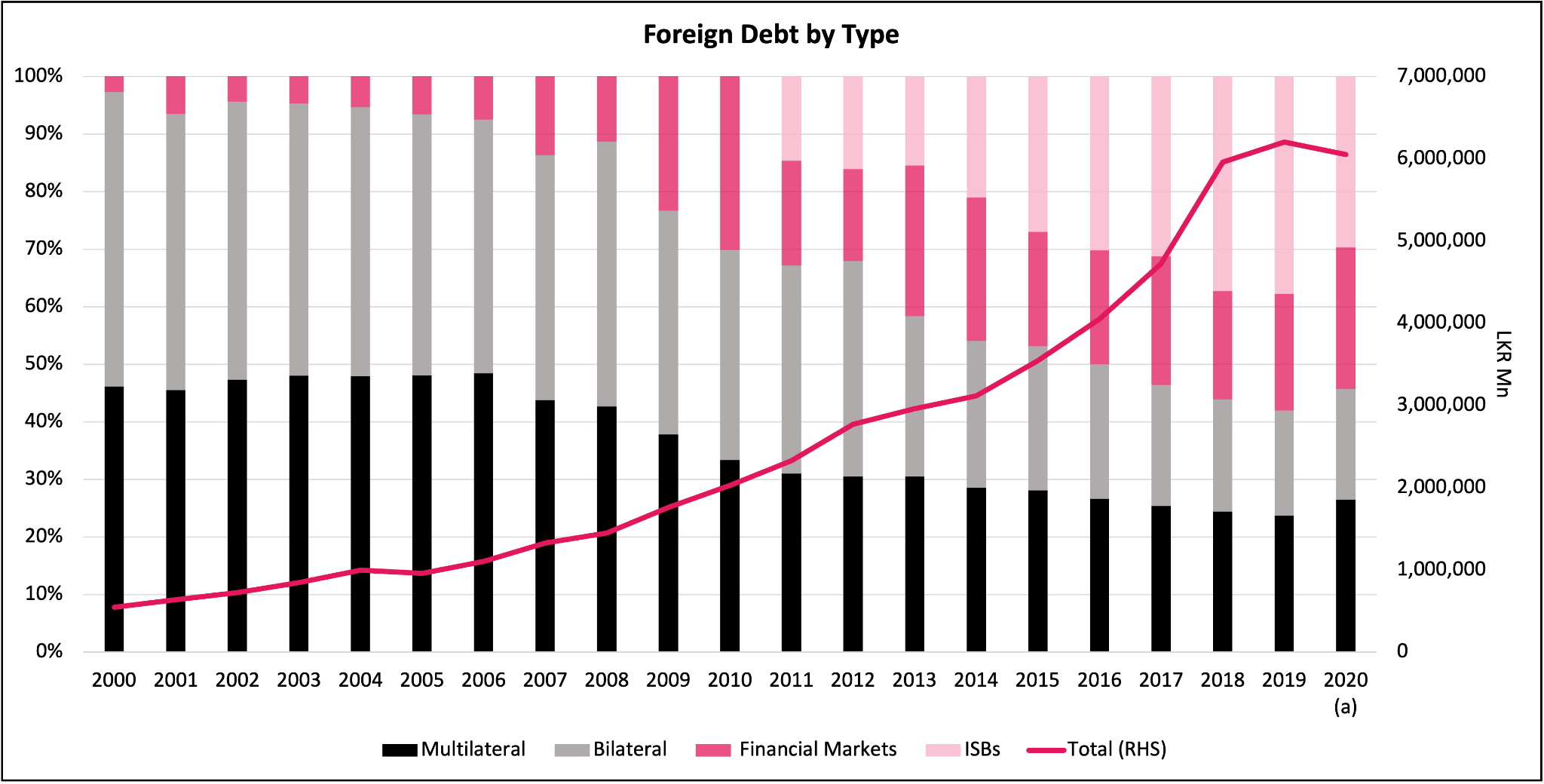

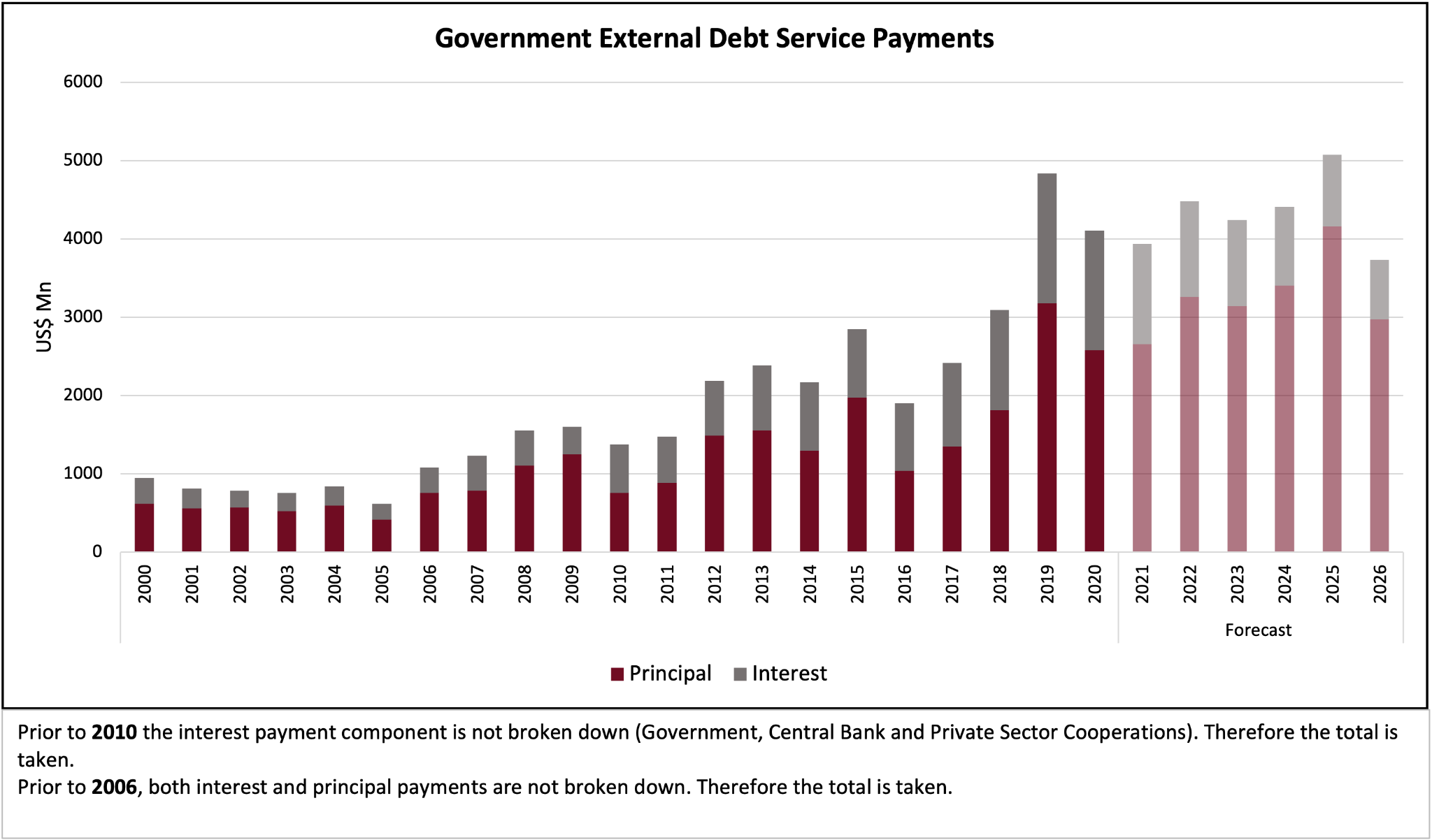

Anyone involved in economic policy-making in Sri Lanka, the IMF included of course, knows that much of the technical work was already done. When the staff-level agreement was signed in September last year, there was a great deal of reform that just required political will and nothing else. Cabinet had approved an earlier version of the new central bank bill during the last days of the Samaraweera ministry. Placing energy price formulas on a statutory footing shouldn’t take more than a day’s drafting. Fiscal rules legislation was already in a relatively advanced stage. Non-legislative measures could also have been mandated - the state could readily have divested its stakes in Sri Lanka Telecom and Lanka Hospitals. These firms are already listed with established valuations. Considering the 200 days between the staff-level agreement in September and board approval now, we had more than enough time to list the major state banks and Sri Lanka Insurance; maybe even privatize the East, Jaya and Unity container terminals. After all, for better or worse, remember the plantations were effectively privatized within fourty-eight hours. These delays are all the more astonishing due to the hypocrisy of asking for favours from our creditors while refusing to sell underperforming assets.

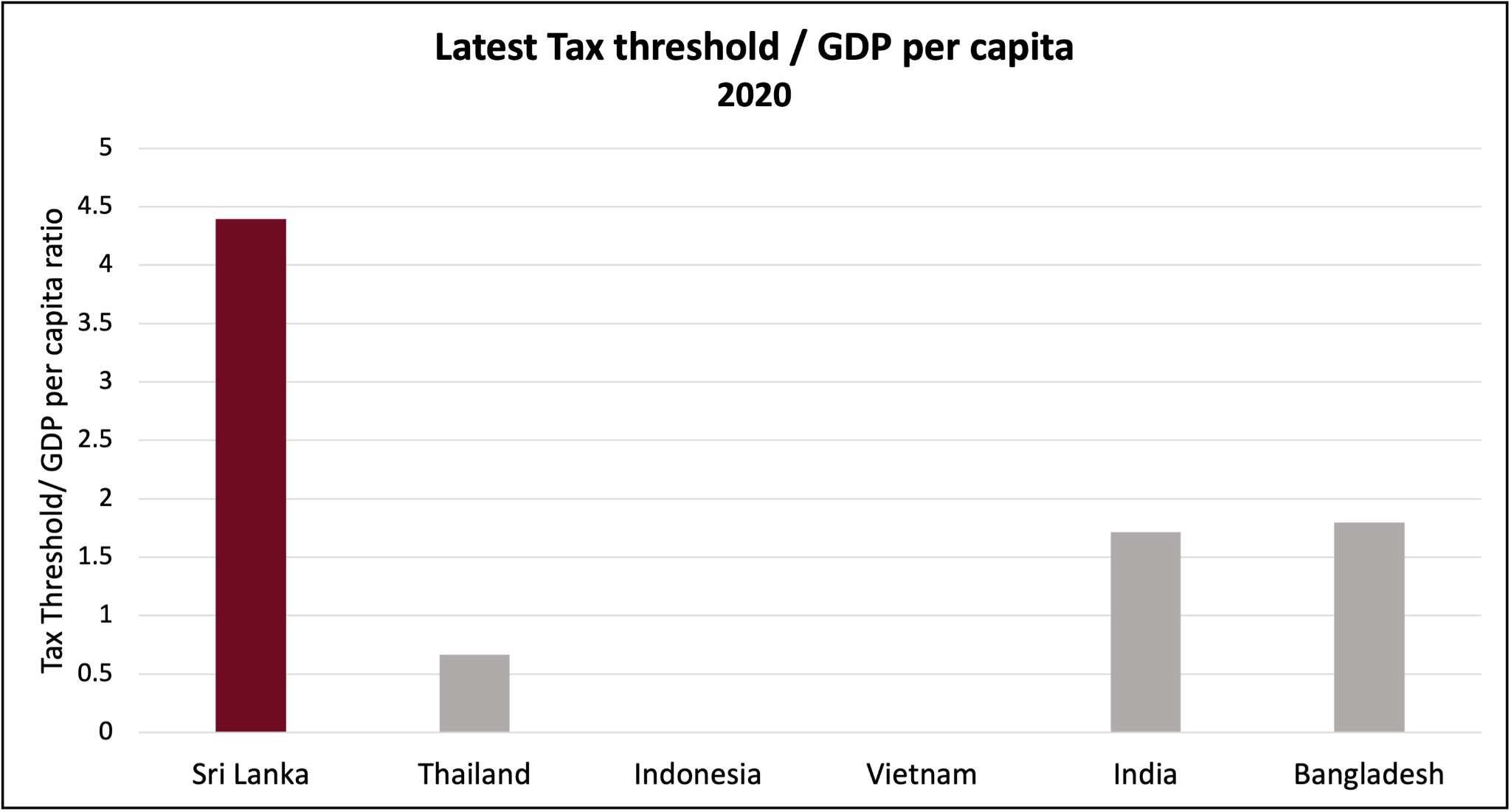

Primary balance vs growth

Considering the political cost of market pricing energy and increasing taxes, from a political point of view, there is tremendous incentive for the political leadership to undertake structural reform in return for less pain. Sri Lanka’s future debt sustainability (or lack thereof) is a function of current and future (a) government revenue, (b) government expenditure and (c) GDP growth. By raising Sri Lanka’s growth potential, both the IMF and long-term creditors could and should have been willing to trade-off revenue and expenditure targets for entrenched, high quality structural reform. The one percent rate hike - which the central bank opposed - just before placing Sri Lanka on the board agenda illustrates this well. Clearly, this temporary, one-off one percent increase in interest rates was considered decisive for obtaining board approval. Why then was not actually passing the central bank bill in Parliament - which is likely to shape inflation rates for decades? Note that in my view, the IMF’s bargaining power at this juncture could be so strong that a trade-off between primary balance linked targets and structural reforms may not exist. The IMF may have been able to demand both. That is the IMF could have had the cake, eaten the cake and called it a letter of intent.

Primary balance today vs primary balance tomorrow

Even if one does not buy the argument of reducing the primary balance target today in exchange for growth tomorrow, two strategies superior to the status quo could have been pursued.

First, instead of trading off the primary balance versus growth, we could have exchanged a primary balance improvement today for a larger primary balance improvement tomorrow. The IMF could have permitted reducing the primary balance target today in exchange for entrenched reforms that result in a paradigm shift in Sri Lanka’s primary balance trajectory for the future. For example, coming back to the central bank bill, through greater depoliticization and limitations on central bank funding of government deficits, this landmark reform is likely to change Sri Lanka’s medium to long term primary balance trajectory. The ‘net present value’ of this change in primary balance terms - even when discounted for the probability of it being unenforced - is likely to be greater than a few percentage point changes in the primary balance today.

Optimizing this trade-off would also have the added benefit of placing less pain on the public and reducing the extent of contractionary policy amidst Sri Lanka’s worst economic crisis in decades.

Second, there are some measures that can improve the primary balance today, and tomorrow. A good example is the sale of shares in state banks. The sale of minority stakes in BOC and People’s Bank will raise money for the exchequer, boosting the primary surplus. However, especially if the banks are listed, it will also make it more difficult for the state banks to permit the government to create enormous contingent liabilities via loans to the CEB and CPC, resulting in a healthier future primary balance.

Overdiscounting the future

The argument often made in response is that the IMF cannot tradeoff the certainty of hitting quantitative targets today, in return for structural reforms whose fruits may not materialize tomorrow. This view is misguided. First, deep understanding of context enables a reasonably good assessment of the probabilities of a structural reform producing a desired outcome - enabling the computation of rough expected values. For example, we know that once a privatization takes place it is unlikely to be easily undone. Second, even after first discounting on the basis of probabilities, a second round of discounting can take place to compensate - to some degree - for the uncertainty inherent in structural reform.

Bailamos

There are two dancers in this toxic tango. They both need to take stock of the past, break with it and dance a new dance. Introspection is a good start. The IMF and our government should get together and commission a review of all past programmes to inform the design and implementation of the current programme. In the meantime, the priority should be to ensure as many structural reforms as possible are pushed through prior to the first review. If we are able to use entrenched, high-quality structural reform to credibly improve Sri Lanka’s medium term growth and primary balance trajectory, we should be able to avoid some of the short-term pain and contraction that we would otherwise experience. Then, maybe instead of toxic tango, we can look forward to a solid baila session. With the President, as he did with Iranganie Serasinghe, accompanying the IMF’s managing director for a round of kaffirhina. After all, compared to austerity, structural reform is a sumhiri pane.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.