By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

Tourism is one of the key sectors driving Sri Lanka’s economic recovery. It has long been a pillar of the economy, yet few seem to fully grasp the basic economic logic required to elevate the industry to the next stage.

One critical component of the tourism value chain is lodging. The hospitality experience is largely built around where tourists stay – whether in a hotel, boutique property, or small guesthouse listed on platforms like Airbnb or Booking.com.

Lodging often accounts for the largest share of total tourist expenditure and supports a wide range of ancillary services including restaurants, entertainment, and transport.

Lodging, however, is a capital-intensive industry. The investment is heavily front-loaded: before hosting the first guest, the property owner must invest significantly in construction, infrastructure, and setup.

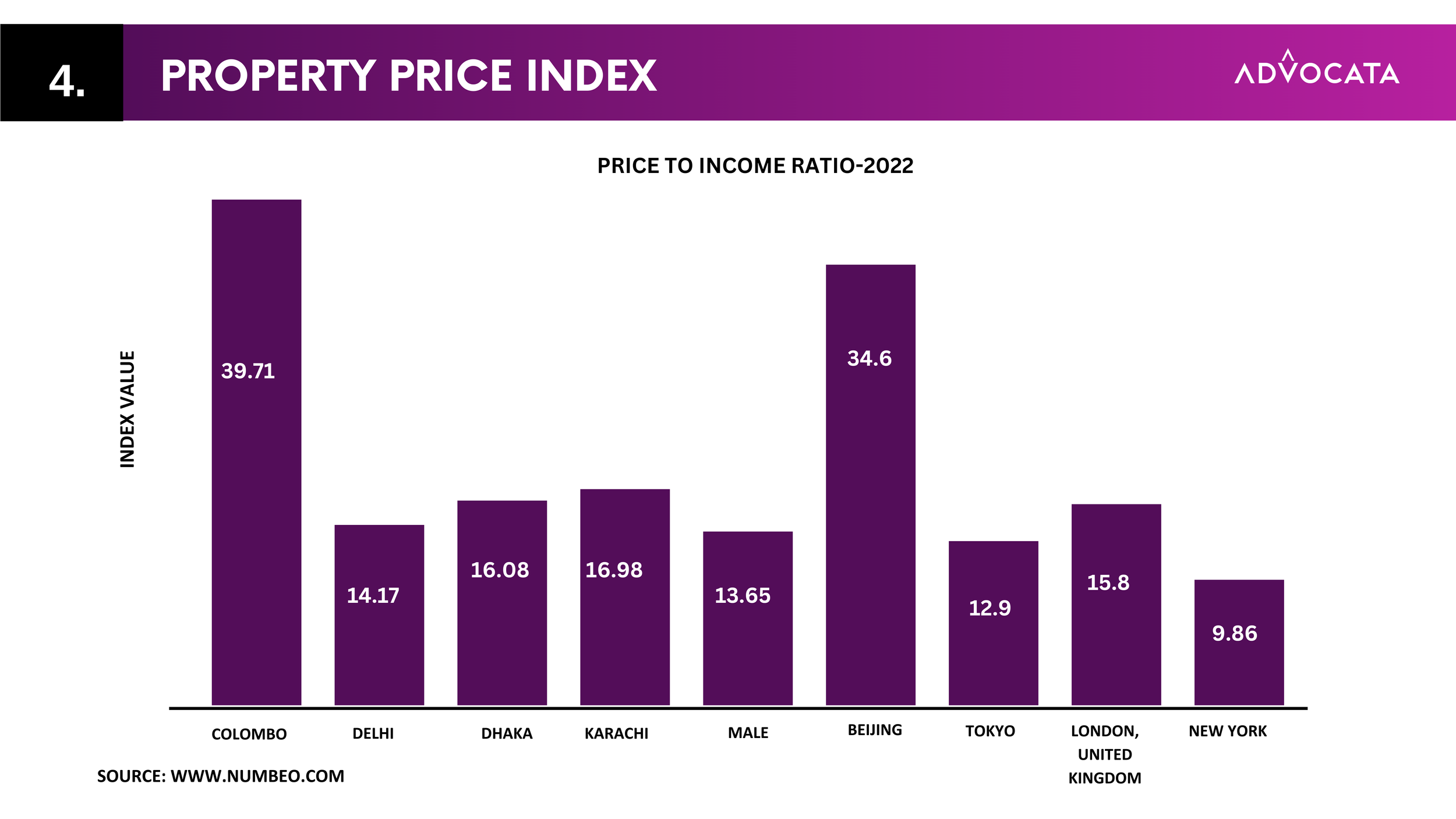

In Sri Lanka, the cost of construction is approximately 40% higher than in other countries in the region. This means that hoteliers need significantly more capital just to get started. To make matters worse, the cost of capital (i.e. borrowing costs) is relatively high and utilities like electricity are more expensive than in competing destinations.

These higher input costs drive up room rates, making Sri Lanka’s tourism product less competitive. Much of this is due to protectionist tariffs on essential construction materials such as cement, steel, tiles, bathroom fittings, and more. As a result, hoteliers pass these costs on to tourists.

Moreover, the hotel industry requires refurbishment every five years to maintain standards. The high cost of construction makes this cycle financially challenging and erodes competitiveness over time. Although Sri Lanka aims to attract high-spending tourists, price remains a key lever in travel decision-making and high costs significantly squeeze hotelier profit margins, especially for small and medium-sized establishments, which account for the majority of room inventory.

Labour and productivity challenges

Labour is another critical component of the hospitality equation. Typically, the industry recruits unskilled workers and trains them to deliver services. Wages are structured so that service charges make up a significant portion of employee income.

However, if there is labour redundancy – more employees than needed – the service charge gets divided among more people, reducing individual earnings. This can lead to moonlighting and low productivity, as employees seek secondary sources of income.

Staff attrition is also common, with employees constantly on the lookout for better-paying opportunities. Productivity is measured through revenue per employee; fewer employees delivering the same service increases profitability and also boosts staff take-home pay via higher service charges.

A compelling case study is Cinnamon Red, presented by Hishan Singhawansa at the Advocata ‘Ignite Growth’ conference. He demonstrated how productivity improvements could increase revenue per employee. Cinnamon Red operates with an employee-to-room ratio of 0.75, compared to the industry average of 0.8-1.6, depending on hotel category (luxury vs. budget).

The hotel’s employee hours per occupied room are around five – roughly twice as productive as peers in the same category. As a result, revenue per employee is double that of competitors, and service charges are 1.6 times higher than other hotels and resorts. This shows that productivity gains translate into higher earnings for employees and better outcomes for businesses and consumers alike.

Cinnamon Red achieved this by removing unnecessary human intervention and embracing automation and self-service: self-check-in kiosks, vending machines, digital concierge services, and self-ordering systems. This transformation was part of a broader strategic repositioning, focused on multitasking and culture change.

The path forward for SL

If Sri Lanka is serious about transforming its tourism industry, reforms are essential.

Key steps include:

Reducing protectionist tariffs on construction materials to lower costs and improve competitiveness

Improving labour productivity across the board, ensuring that skilled workers are retained and better rewarded

Investing hotelier margins into delivering world-class experiences rather than simply covering high operating costs

There is also a need for a global tourism campaign, eased visa regulations, the removal of price floors for five-star hotels, and other policy changes, but none of this will matter unless we first understand the economic logic of tourism.

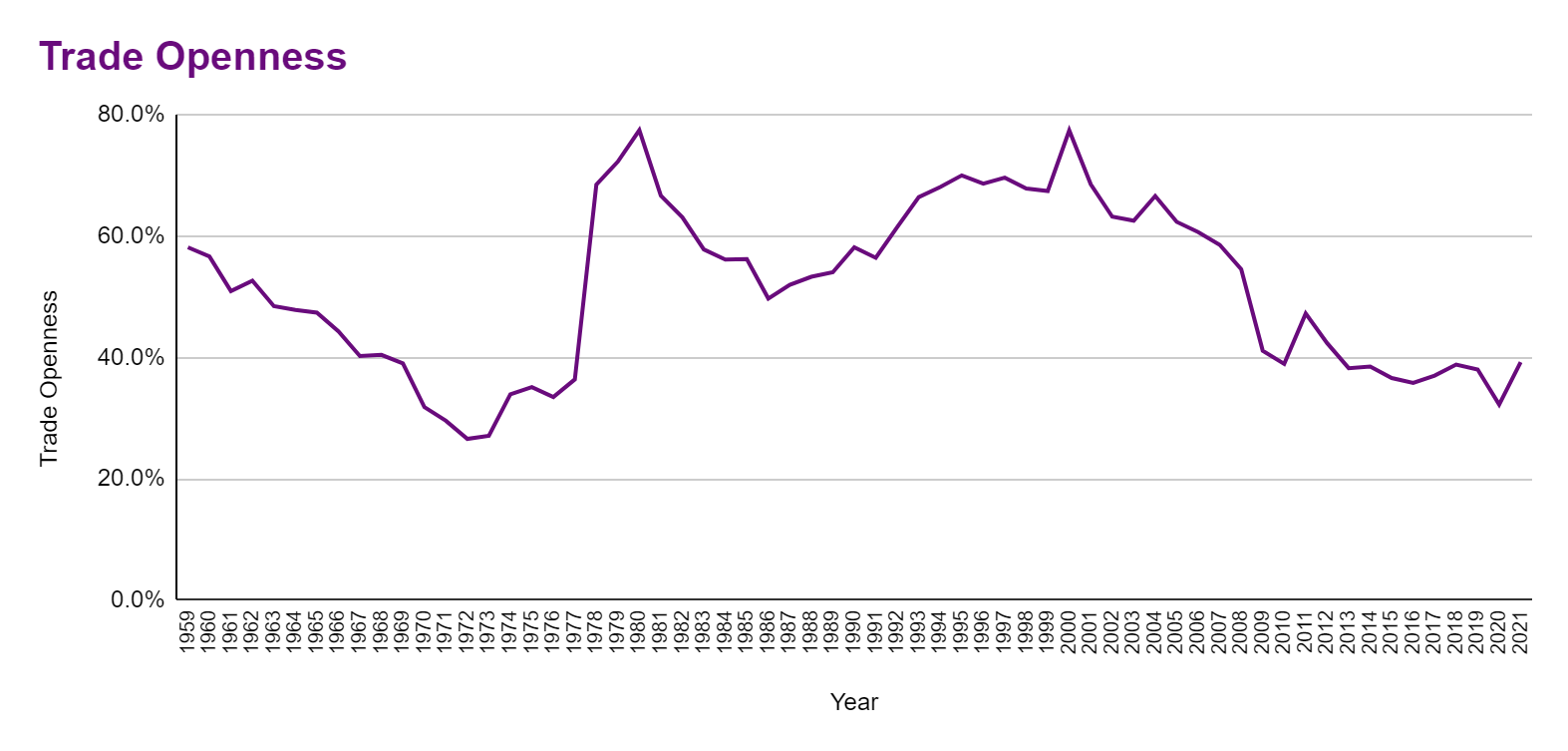

At the same time, we must recognise that tourism is highly vulnerable to external shocks. In recent years, Sri Lanka’s tourism sector has suffered due to:

The constitutional crisis in 2018

The Easter Sunday attacks in 2019

The Covid-19 pandemic (2020-2021)

The economic crisis in 2022

These events underscore the risk of over-reliance on a single sector. While tourism can be a powerful engine of growth, it should not be the sole driver of economic recovery. A balanced, diversified economy is essential for long-term resilience.

Monthly employee earnings (LKR) vs. estimated living wage

(Source: Slides presented by Hishan Sinhawansa at the Advocata ‘Ignite Growth’ conference)