By Dhananath Fernando

Originally appeared on the Morning

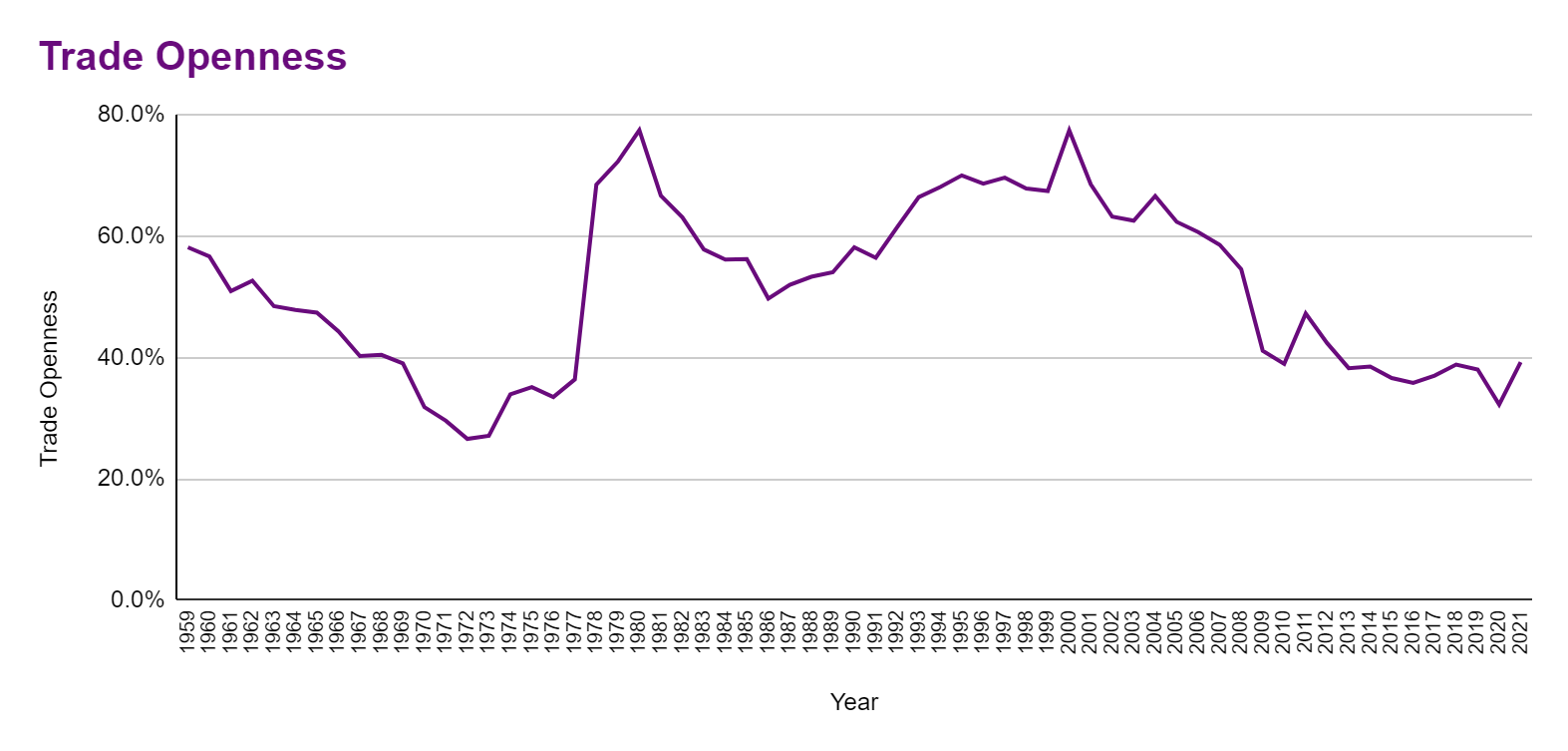

Sri Lanka has been trying to solve its export puzzle for a long time, with a new export target set at $ 36 billion by 2030.

As of November 2024, the country had approximately $ 11.6 billion in merchandise exports and $ 3.1 billion in services exports, totalling around $ 16 billion. Over the next five years, exports are expected to double, requiring an annual compounded growth rate of approximately 14%.

Many policymakers define Sri Lanka’s export challenge as a lack of diversity in the export basket, limited access to international markets, or insufficient value addition. While these factors are valid, the core issue is that Sri Lanka is not competitive.

This lack of competitiveness is not due to an inherent incapability but rather the result of policies and structural inefficiencies that have rendered the country uncompetitive. Often, this fundamental issue is misdiagnosed as a lack of targeting, leading to constant shifts in focus towards different sectors or products every three years without addressing the root causes of uncompetitiveness.

Addressing competitiveness

Addressing public policy challenges is inherently complex, as solutions impact various stakeholders, making change management difficult.

One of the primary mistakes governments and policymakers make is attempting to target specific sectors for export growth. Instead, focus should be placed on sectors where Sri Lanka has a competitive advantage.

The only way to determine competitiveness is through practical application – by actively engaging in export activities rather than relying solely on theoretical projections. In the modern economy, competitive advantage extends beyond specific products to elements such as design, lead times, and supply chain efficiencies – factors that may not be immediately evident to a single decision-maker.

The global trade landscape is shifting from finished products to parts and components within value chains. However, when the Government plans around traditional industry categories, it often overlooks this evolving reality.

For any product or component to be manufactured competitively, key resources – land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship – must be accessible and efficient. Sri Lanka’s export underperformance, poor diversification, and lack of market access stem largely from bottlenecks in these factor markets.

When essential factors of production do not function effectively, innovation stagnates, restricting export diversification and the development of components for various products, including value-added goods.

If businesses can achieve higher margins through value addition, they would naturally do so. If they choose to export raw materials instead, it suggests the presence of barriers, misaligned incentives, or a competitive disadvantage in value-added production.

To illustrate this, consider the hypothetical case of exporting iron ore. A country rich in iron ore but burdened with high energy costs will find exporting raw ore more advantageous than converting it into steel. Conversely, a country with lower energy costs, proximity to industrial zones, and high steel demand will have a competitive advantage in steel production.

This principle applies across all industries – cost structures, infrastructure, and resource availability dictate competitiveness.

A complex problem

Compounding the problem is the interconnected nature of these issues. Solving one aspect alone will not fix the broader export challenge.

In Sri Lanka’s case, high energy costs place any export industry at a price disadvantage. Subsidising energy is often proposed as a solution, but ultimately, taxpayers bear the cost.

Similarly, labour costs remain high due to regulatory barriers. For instance, if a major tech company wanted to relocate its regional office to Sri Lanka, the country lacks an adequate pool of IT graduates. Addressing this would require either allowing foreign professionals to work in Sri Lanka or significantly upskilling the local workforce.

Export development also requires capital and entrepreneurship. Capital can be acquired through debt or equity, but debt financing is currently not a viable option for Sri Lanka. Equity investment remains possible, but attracting such investment necessitates improving Sri Lanka’s investment climate. This highlights the urgent need for reforms within the Board of Investment (BOI).

Additionally, facilitating foreign entrepreneurs’ ability to enter Sri Lanka – through streamlined visa processes and work permits – is essential. The Department of Immigration and Emigration must play a role in this.

For capital to flow, investors require developed lands with ready-to-use infrastructure, minimising lead time and operational delays. Without addressing these factor market inefficiencies, traditional export strategies will continue to fail. The global export market is now highly fragmented, with the future lying in the production of components and participation in global value chains rather than focusing solely on finished products.

Ultimately, the export sector is too complex for any single individual or institution to plan entirely. It is an organic, competitive field where businesses strive to add value through quality and cost efficiency.

The role of the Government should be to facilitate this process by removing barriers and creating an environment conducive to competition. If the right conditions are in place, export growth will naturally follow and Sri Lanka will achieve its ambitious targets.