In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

Sri Lanka’s location at the midpoint of international trade routes, positioned at the centre of the Indian Ocean, is a fact that we probably know by heart. But what’s important is the question whether we are exploiting this position. Our ports and good policy decisions are the tools that allow us to change geography into tangible benefits. The performance of the Colombo Port has been exemplary. It recently handled its seven millionth container and was ranked the fastest-growing port in 2018. However, with the Colombo Port operating at approximately an 80% capacity, this growth and the benefits it brings have an expiration date.

What is the ideal role of the government in the shipping industry?

The government should most definitely not be both a player and a regulator. Right now, the Government plays both roles, and the potential for a conflict of interest is enormous. It also means that it is increasingly difficult for competitive neutrality to be maintained. However, the government should not be completely removed from the industry. The role of the government lies solely in being a landlord and regulator, for if the Colombo Port is to grow while remaining efficient and profitable, regulation is required to address anti-competitive practices, monitor performance, and enforce standards. Of course, when advocating for government regulation, one wants to steer clear of the miles of red tape that the government is fond of. A caveat of this argument is that a balance be struck, so that regulation does not stifle innovation or investment.

What makes economic sense?

Establishing the hard and soft infrastructure a port requires is a capital and time-intensive task. There also needs to be strong commitment, which the Government lacks. Colombo International Container Terminal (CICT), which is a joint venture between China Merchants Port Holdings Company Ltd. and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA), signed a BOT agreement in 2011. The terminal was operational by 2013. In comparison, the construction of the breakwater for the Jaya Container Terminal (JCT) run by the SLPA took four years, from 2008 to 2012. CICT developed an entire terminal in less time than it took the SLPA to construct the breakwater for its existing terminal.

Lack of direction and consensus from decision makers in government have resulted in the East Container Terminal (ECT) – a strategically important terminal remaining unused and idle. It is clear that the Government needs to step aside and allow the private sector to come in. This is evidenced by the performance of the South Asia Gateway Terminal (SAGT), which is operated on a BOT basis with the Government of Sri Lanka and a consortium of local and international establishments, which was awarded the “Best Terminal in the Indian Subcontinent Region” for the third consecutive year in 2019 and won the “Best Transhipment Hub Port Terminal of the year” at the Global Ports Forum.

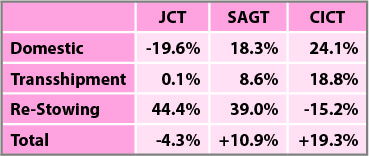

Percentage change in TEU handling from 2016 to 2017 (Source: Ministry of Ports and Shipping, Performance Report (2017), compiled by the Advocata Institute)

When comparing the success of the different terminals, the same conclusion can be drawn. Looking at the comparison of the number of Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEUs) handled by the terminals from 2016 to 2017, the CICT is the best performer. Interestingly, while both SAGT and CICT have enjoyed an increase of 10.9% and 19.3% in TEU for 2017, JCT has witnessed a 4.3% drop. The privately-operated terminals outperforming the SLPA Jaya Terminal speaks volumes.

“Seaports are interfaces between several modes of transport, and thus they are centers for combined transport … they are multi-functional markets and industrial areas where goods are not only in transit, but they are also sorted, manufactured and distributed. As a matter of fact, seaports are multi-dimensional systems, which must be integrated within logistic chains to fulfill properly their functions.”

Ripple effects of private ownership

This definition by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development succinctly describes the importance of ports and port infrastructure, and accurately shows how ports cannot work in silos. They are an integral component in a wider network of business, infrastructure, supply chains and employment. If we want profitable and efficient ports, we need similarly performing ancillary services.

Ancillary services and ports enjoy a symbiotic relationship. On one hand, ancillary services are series of economic activities which provide services and create employment; which are dependent on the port. On the other hand, the port benefits from efficient ancillary services as they make the port and its terminals more attractive to clients and boosts its own performance.

Ancillary services include logistics, bunkering, marine lubricants, freshwater supply, off shore supplies and ship chandelling, warehousing and many more. These services, and their ability to grow is affected by the general functioning of the port, and therefore is affected by the ownership of the terminals.

For a port to survive, ancillary services need to constantly innovate and remain productive. There is no need for this article to expound on how the government is not the place to go to when in search of innovation. This is clearly the forte of the private sector. This is backed up by the fact that so far, private ownership of terminals and profitability go hand in hand. In short, if profitable and productive terminal creates a well-functioning port, allowing ancillary services to grow; then we should be looking to the private sector for investment and not the government.

What is happening with the ECT?

As mentioned above, the Colombo Port is fast growing. However, if you were to look at the Colombo Port from one of the many high rises in the Fort area, spotting the East Container Terminal would not be difficult – it’s the only terminal with nothing happening. No cranes, no ships, no activity.

The East Container Terminal is not significant simply for its disuse. Compared to the West Terminal, it is situated in the middle of the new port and the old port of Colombo. This gives it an advantage as it is closer to all other terminals and moves inter-terminal cargo a smaller distance. This gives it an important edge as inter-terminal cargo is an important component of transshipment. The depth of the ECT, at 18m allows it to handle container shipments, adding to its value. In short, the ECT has a clear operational advantage.

It is evident that the country has lost out in this scenario. In a port that is as fast growing as the Colombo port, the decision makers of this country have, for a variety of reasons, not developed the ECT. The Sri Lankan government has taken many stances over the years. It both invited expressions of interest and business proposals for the development of the ECT and cancelled tenders, insistent that the ECT will be run by the Sri Lanka Ports Authority – sending mixed signals to interested parties, and effectively ensuring that investors are reticent, and development of the port has stalled.

Politics have dictated the government’s decisions on the ECT, and the result is that the country has lost out. In shipping the government has an important role to play in regulation and ensuring standards are adhered to, but it cannot be both a player and a regulator. The performance of the JCT in comparison to the private terminals makes it clear that government is not as effective as the private sector, it should limit itself to the task of regulation. In conclusion, the ECT should be opened for private ownership as soon as possible, following the precedent set by the BOT models of the CICT and SAGT.

Aneetha Warusavitarana is a Research Analyst at the Advocata Institute. Advocata is an independent policy think tank based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. They conduct research, provide commentary, and hold events to promote sound policy ideas compatible with a free society in Sri Lanka. She can be contacted at aneetha@advocata.org or @AneethaW on twitter .