Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

World Food Day falls on 16 October. In Sri Lanka, food security has been a topic of discussion for a considerable period of time, especially gaining prominence during the Covid-19 pandemic.

During that period, there was confusion between food security and self-sufficiency. Instead of focusing on ensuring food security, the emphasis was placed on self-sufficiency, with the belief that all food consumed in Sri Lanka should be produced within the country. There were even discussions among Sri Lankans about shifting from using lentils (dhal) to locally-grown maize.

After approximately two years, when we assess the Global Food Security Index report, Sri Lanka is ranked 79th out of 113 countries. Food security isn’t solely about achieving self-sufficiency by producing all the food within the country; it encompasses the affordability, availability, quality and safety, as well as a nation’s exposure and resilience to natural resource risks.

Prior to the inclusion of the natural resources and resilience component, Singapore led the Global Food Security Index. However, after adding this component in 2022, Singapore dropped to the 28th position, with Finland now topping the Index. India is in the 68th position, Nepal in the 74th position, and Bangladesh in the 80th position, just one spot below Sri Lanka.

Due to the economic crisis, characterised by high inflation rates, particularly in food prices, the number of people who were food insecure exceeded six million. This number has now decreased to less than four million, emphasising the significant role economic stability plays in ensuring people’s food security.

Sri Lanka’s food security has always been a challenge due to economic policies that have been against market dynamics. Monetary instability resulting from the unfettered levels of money printing led to food inflation, affecting the affordability of food.

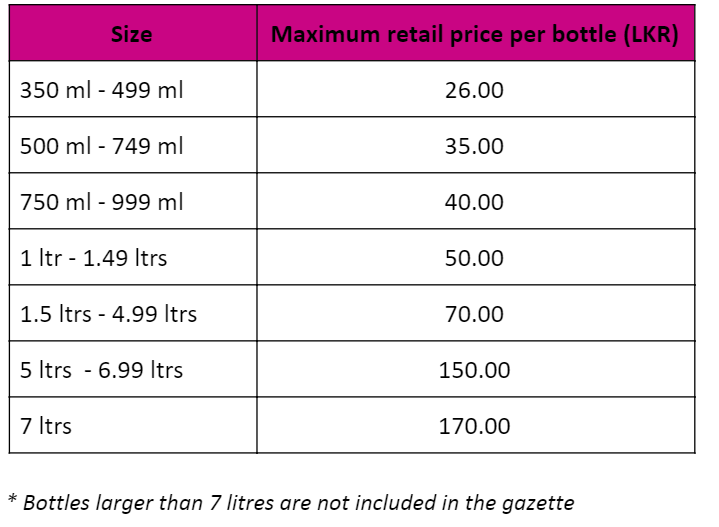

The Government’s imposition of price controls led to shortages of protein sources such as eggs and chicken, further impacting the availability of food. Additionally, the Government imposed a Special Commodity Levy (SCL) on selected food items as a protectionist measure, maize being a prime example, driving up prices.

Maize is a key raw material for the aquaculture and poultry industries. Price volatility in maize also affects the prices of poultry products and other locally consumed protein sources, sometimes impacting the competitiveness of our agricultural exports.

The Government’s approach, whether through higher tariffs or import bans, is equally detrimental. Our food security structure is simply unsustainable, with weak and unpredictable supply chains and inconsistent policies.

Ensuring food security involves addressing both macro and micro issues. A holistic approach, taking into account land rights, is essential. The documentary recently released by the Advocata Institute titled ‘Land, Freedom and Life’ highlights the challenges faced by farmers due to the absence of land rights, hindering their access to capital or technology to enhance productivity.

In addition to land rights, water management is another critical aspect that needs serious consideration. Currently, our water usage in paddy cultivation is unsustainable. We consume approximately 1,400 litres of water to produce 1 kg of rice. Even if we price a litre of water at 50 cents, the cost of the rice we consume would significantly surpass current prices.

With the challenges posed by climate change, future water availability cannot be guaranteed. Despite the number of people experiencing food insecurity declining, our approach in food production is not sustainable. Another local or global shock could easily set us back.

The Government has attempted various approaches such as providing subsidies for farmers, free meals for school children, and free nutritional packages for women during maternity. However, in order to truly address Sri Lanka’s food security crisis, a multifaceted approach is required.

This should begin with macroeconomic stabilisation, providing land titles for farmers and agro-companies to enhance agricultural productivity, reducing labour costs in agriculture, recognising the interconnectedness of markets, and allowing market forces to operate.

Until these issues are resolved, World Food Day will remain a day for discussing problems without implementing solutions.