In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Aneetha Warusavitarana

Rising rates of obesity and incidence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have long been a point of concern for the Sri Lankan health sector. As a country, we have made significant strides in addressing the challenge of communicable diseases, and now policymakers are shifting focus onto NCDs. The imposition of a tax on sweetened drinks in 2018 was a point of serious debate. It was both lauded as an admirable step in tackling the issue of NCDs, while simultaneously facing serious protest from the soft drink industry.

In 2018, the 51-day Government reduced this tax, and now the present Government stated that it will re-impose the tax, citing health concerns as the motivation behind it. While a final decision is yet to be taken on this, given that this is the same Government that imposed the tax, it seems likely that we will be seeing a tax increase.

Political packaging

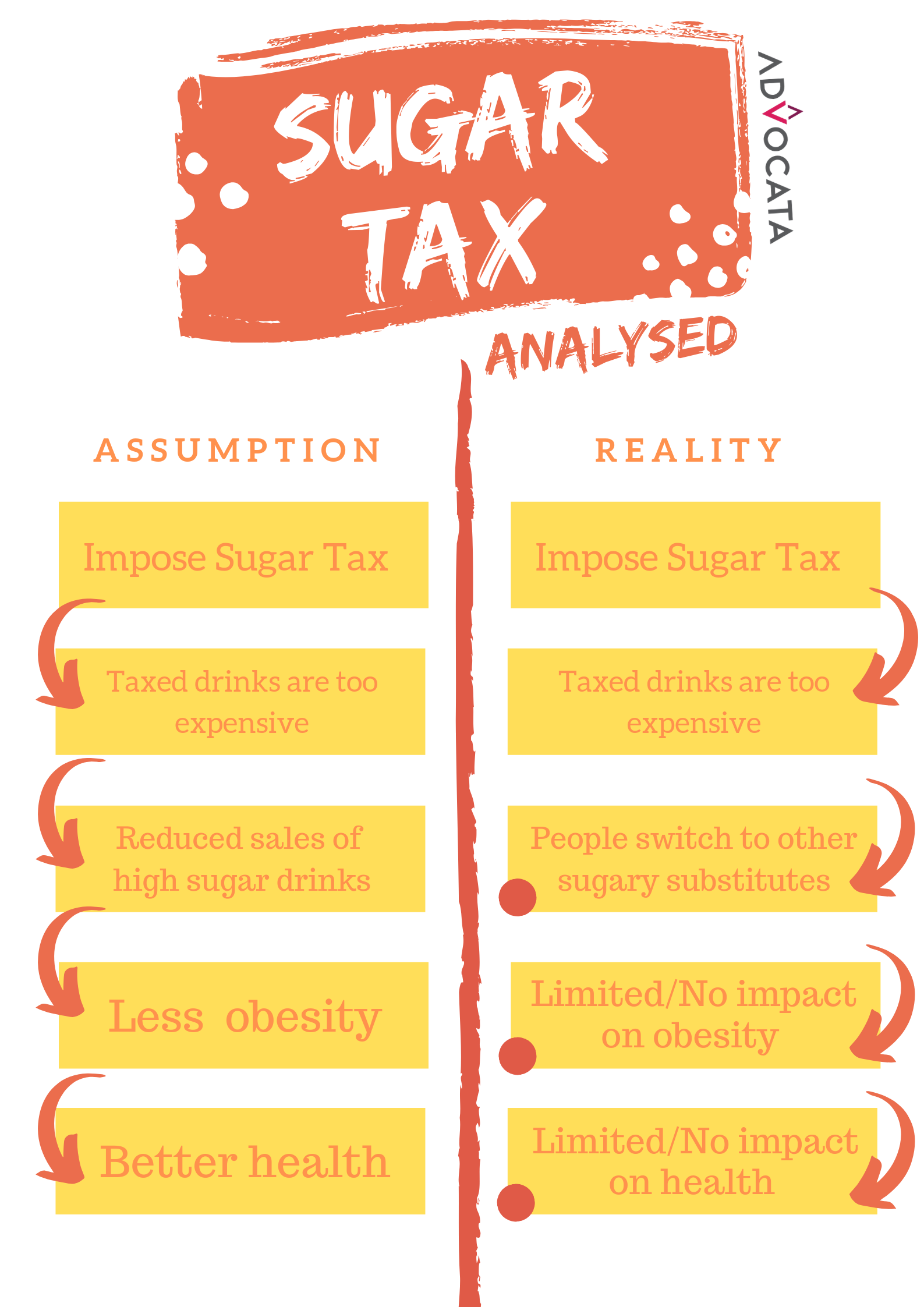

Imposing this tax is an easy way to gain some political mileage. The narrative presented is simple – obesity and non-communicable diseases are a serious health concern for the Sri Lankan population. Sugar consumption is a contributor to this problem and as a responsible Government, they need to take steps to discourage consumption – this will be done through a tax per gram of sugar in carbonated drinks. In essence, the tax is packaged as a health-positive policy measure. Indeed, at face value, the tax does present as such. However, there are a few questions which can be raised.

Is this tax fair?

There are two things in life that are certain – death and taxes. While it may be that we will have to continue paying taxes, these taxes should be sensible, effective, and should not be prohibitively burdensome. This idea has been espoused in basic principles of taxation to ensure the tax is effective and equitable. One of the principles the OECD expounds is that of neutrality: “Taxation should seek to be neutral and equitable between forms of business activities.” Neutrality also means that the tax system will raise revenue while minimising discrimination in favour of or against an economic choice.

In the case of the sugar tax being imposed by the Sri Lankan Government, it is clear that the principle of neutrality is not adhered to. At a fundamental level, it is a “sin tax” or a “fat tax” – a tax being imposed to change the economic choices of the population – the aim of the tax is not to raise revenue, but to shift consumer behaviour away to more healthy options. Given that the sugar tax is applicable only to carbonated drinks, and excludes other sweetened drinks like fruit juice or milk packets, it is clear that the principle of neutrality has been ignored here.

Does unfair equal ineffective?

The principle of neutrality in taxation is all well and good, but does this affect people? The answer is yes. When the principle of neutrality is violated and a tax is imposed in a manner that is inequitable to business activities, it loses its effectiveness. The objective of this tax is to discourage the consumption of carbonated drinks with a high sugar content, to achieve a higher goal of good health. When the tax is imposed unfairly only on carbonated drinks, it means the consumers which simply substitute a carbonated drink with an alternative – and there is no guarantee that the alternative will be a sugar-free, healthy one. In fact, the likelihood is that people will switch to a different product with a similar calorie/sugar count – if a bottle of fruit juice is cheaper than a bottle of Sprite in the supermarket, you don’t want to pay more for the bottle of Sprite and you are likely to buy the juice instead. The health concerns will not end up being addressed because consumers will simply substitute one drink which is high in sugar with another drink that is also high in sugar.

Unfortunately, in the case of taxing food and beverages, the issue is that consumers can simply choose to continue to consume a similar level of sugar, just from a different source. Given that this tax only applies to one category of sweetened beverages, consumers can easily substitute it with another, cheaper beverage. There is also the question of whether sales of carbonated beverages drop; international evidence has mixed results. While the WHO (World Health Organisation) applauds these taxes, other studies question whether the tax affects sales of carbonated drinks to an extent that it would have an effect on overall health, or whether consumers are simply shifting preference to an alternative which is an equally sugary substitute.

The final word on this is that there is, at best, uncertainty about whether this tax creates a positive health externality; and at worst, consumers switch to unhealthy alternatives while businesses lose out on revenue.