Originally appeared on Groundviews

By Ravi Ratnasabapathy

This essay examines failures of governance in Sri Lanka. Although discussed within the context of State Owned Enterprises (SOE), they affect many other aspects of public life.

The weaknesses in the governance of SOEs stem from those embedded within the larger political system. These problems can be assessed by an examination of the political system, understanding the incentives of actors and the effectiveness of institutions in directing these towards the public good.

Some examples of general weaknesses in the political system

The power of interest groups

Campaign finance

Weak parliament and committees

Citizens as shareholders

The power of interest groups

People may commonly assume that political actors are mainly concerned with public interest and that the state exists to carry out the wishes of the public.

Unfortunately, the State is made up of people and the dominant motive in people’s actions in the marketplace – whether they are employers, employees, or consumers – is self-interest.

When individuals become politicians they do not suddenly abandon their personal interests and turn into public-spirited individuals who make morally correct decisions in the ‘public interest’.

While most people will base some of their actions on charitable instincts only in rare cases are these likely to be primary motives. Politicians are no different, acting to please interest groups that support them, pushing policies that lead to re-election and pursuing other personal agendas.

Politicians take collective decisions. They are made by politicians on behalf of the public, and not by the public themselves. All decisions involve a trade-off in costs and benefits but when an individual makes an economic choice, they experience both the costs and the benefits. Thus, they will only act if it is in their interest.

In collective decisions, whether they involve giving jobs to graduates or building a road, the beneficiaries (e.g. graduates, road users) are not always the people who bear the costs (taxpayers or homeowners whose property is lost). Further, in a market transaction both sides have to agree, if either disagrees, they can walk away. In political decisions those who disagree cannot walk away, they are bound to accept the decision and bear whatever costs the collective choice demands.

Therefore collective decisions, unlike individual ones, carry wide implications. Good politicians should weigh overall costs and benefits on our behalf to determine if ‘social welfare’ might be increased by the right choices. The question is do Sri Lankan politicians have the motive; or even the capacity, to do so?

When political decisions are made how do we determine what is ‘best’ for ‘the people’? Society is complex, made up of different groups with different interests. The young may be interested in education and jobs, but pensioners may be more concerned with old age security and health care. An ageing population may vote for increased pensions, but if this is achieved at the cost of lower spending on education the young may lose. Different decisions involve different stakeholders with varied interests, making it difficult to identify a single ‘public interest’.

When collective decisions are taken a choice will be made between many competing sets of interests: but only one set of interests can win. Politicians face conflicting pressures from lobbyists, businesses, family and friends. Those with the greatest leverage will win. This is not the same as saying that policies that bring the greatest social benefit will win.

Small, homogeneous groups (trade unions like the GMOA or businesses) find it relatively easy to organise and have a great deal to gain or lose when collective decisions go for or against them. The opposite is true with large groups, such as consumers or taxpayers.

With large groups the impact of collective decisions on a single member is small so they have little incentive to lobby. Being so diverse, they are also difficult to organise.

The result is that concentrated interest groups have a powerful incentive to organise and campaign for policies that will specifically benefit them. By contrast, the general public, with very diverse interests, have little motivation to put effort into public debate.

The protective tax (roughly Rs.10) on a loaf of bread may not amount to much to a consumer but to the flour millers this represents a gain of around Rs.20 billion a year.

When particular groups manipulate policy to win preferential tax or legal privileges this results in a substantial transfer of wealth from the public to privileged groups. In Sri Lanka the practice is widespread; witness the plethora of special tax concessions (about 200 according to the Finance Minister) exclusive import licenses, permits and protective tariffs.

Campaign finance creates incentives for corruption and poor governance

Limits on campaign spending and the need to disclose sources were removed in the 1978 constitution, opening the floodgates. This excludes the majority of citizens, including the educated, from politics.

There are no accurate estimates of the cost of an election campaign but a former Secretary General of Parliament recently stated that this was in the region of Rs. 60-70 million. Conversations with other commentators produced estimates between Rs. 50-100 million, rising to Rs 150 million for those fighting for preferential votes.

The proportional representation system has increased constituency size (campaign costs are proportional to constituency size) while the preferential voting system intensifies political competition (not only must candidates battle other parties, they must also fight within the party). The combination has sparked an arms race in campaign spending.

While costs are lower outstation they are still substantial and far beyond the lawful earnings of an MP who earns a monthly salary of Rs. 54,285/- plus other allowances of around Rs160,000/-.

Politicians turn to wealthy backers, some connected to the underworld, to fund campaigns and provide labour-in return for political protection or rewards. The result is that a group selected on the basis of access to cash and a workforce – not intellect or ability – enters Parliament. Moreover, the need to recover campaign spending means they come into office under obligation to their sponsors, carrying an inbuilt incentive to corruption.

This has undermined the technical capacity of the state; how can proper policy be formulated if the politicians and bureaucrats are ill-qualified to perform the necessary analysis? The bureaucracy has an important role in policymaking, providing objective assessment of policy options, drawing on experience and practical considerations. Unfortunately, decades of nepotism have sapped its capacity. The concept of independent policy analysis does not exist in Sri Lanka, leaving a vacuum vulnerable to capture by special interest groups.

Weak Parliament and committees

Political actors will pursue their own interests, but functional governance systems can check the worst of these impulses. The most important is parliament, which works through questioning government ministers, debating and the investigative work of committees, principally the Committee on Public Expenditure (COPE) and Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) which scrutinise expenditure.

Unfortunately, serious deficiencies exist. Engineering crossovers in return for political office reduces Parliament to a rubber stamp. Thus there is little incentive for MPs to take Parliament seriously. Many don’t even attend.

An analysis showed that less than half the MPs attended at least 75% of the sessions. Even those who attend remain in the house only for the first hour. Attending funerals or weddings is the priority; they recently voted themselves a new monthly allowance of Rs.100,000 for gifts at functions. Once elected, the goal is Cabinet appointment, as this presents opportunities for gain or furthering political careers. Once ensconced, the incentive is to enjoy office, not to risk the privileges by questioning authority. The multiplication of the Cabinet is driven more by the need to lure opposition MPs to maintain a rubber-stamp majority than strictly functional requirements.

The committee system is also weak. Until recently they were ‘Consultative Committees’ chaired by a Minister and structured to aid the executive than hold it to account. With the major overhaul of the system [1] by the Yahapalanaya government – a significant if little known reform in the last three years – these are now known as ‘Oversight Committees’ and their function is now much better geared to scrutiny and accountability-but much more needs to be done.

COPA/COPE are under-resourced; their reports complain of a lack staff (particularly audit) and proper IT systems. Further, the government is not required to act on the recommendations of these committees (although ministers must now respond to findings) within any stipulated period of time, leaving the accountability loop open.

Despite many limitations, these committees have uncovered multiple grave malpractices that point to fundamental control weaknesses. The fact that only a minority of institutions seem able to furnish an unqualified audit report suggests much more lurks undetected.

Citizens as shareholders

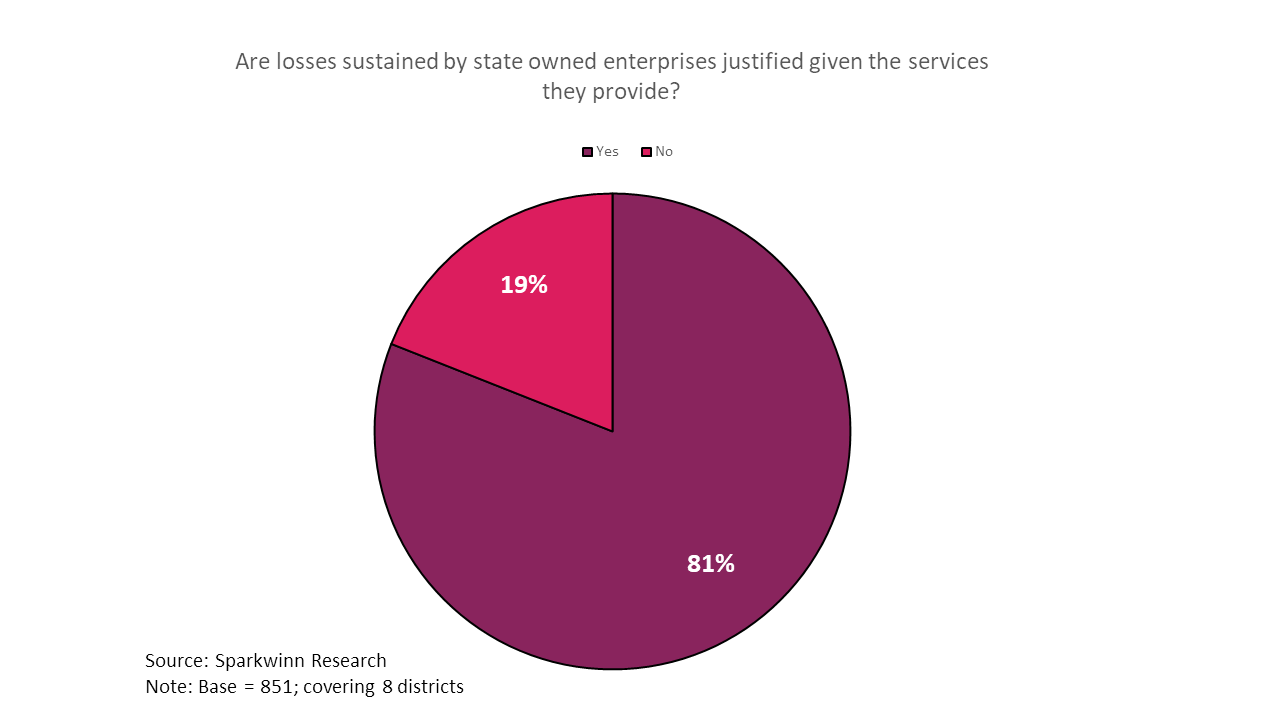

If politicians do not hold SOEs to account can citizens, the ultimate “owners” exert any meaningful oversight? Unfortunately not because:

They have no legal standing as owners;

The fragmented nature of the “ownership” creates a collective action problem: no one citizen, even ones who are seriously interested, has an incentive to bear the costs required to monitor the managers.

Oversight is costly, and time and effort must be spent on monitoring performance if malpractice is to be detected. This task is made more difficult as citizens lack ready access to information. As no direct rewards accrue to a diligent citizen from such action there is little incentive to expend the effort to do so; citizens depend on politicians to do this. As discussed previously, the politician has no clear incentive, especially since they are not held accountable for poor performance.

The main mechanisms to address these two layers of agency costs are corporate laws and political and legal institutions. The weaknesses of the political institutions have been discussed above and corporate law are rarely enforced on SOEs.

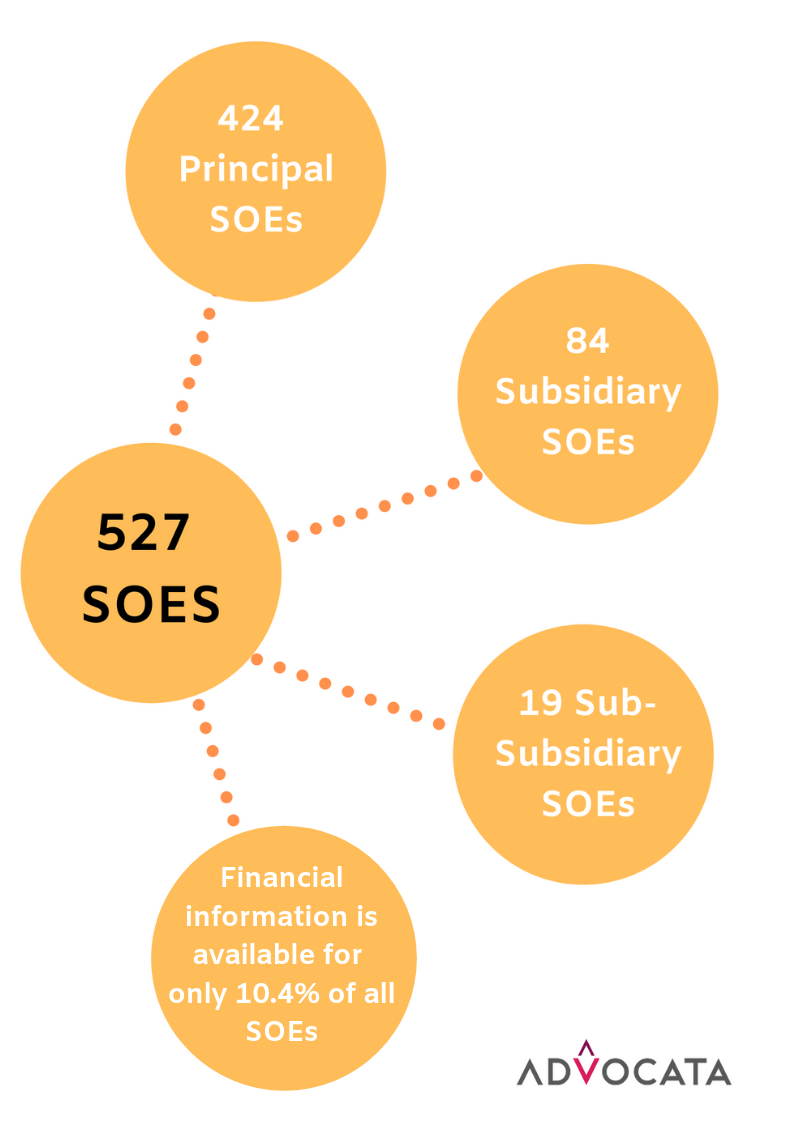

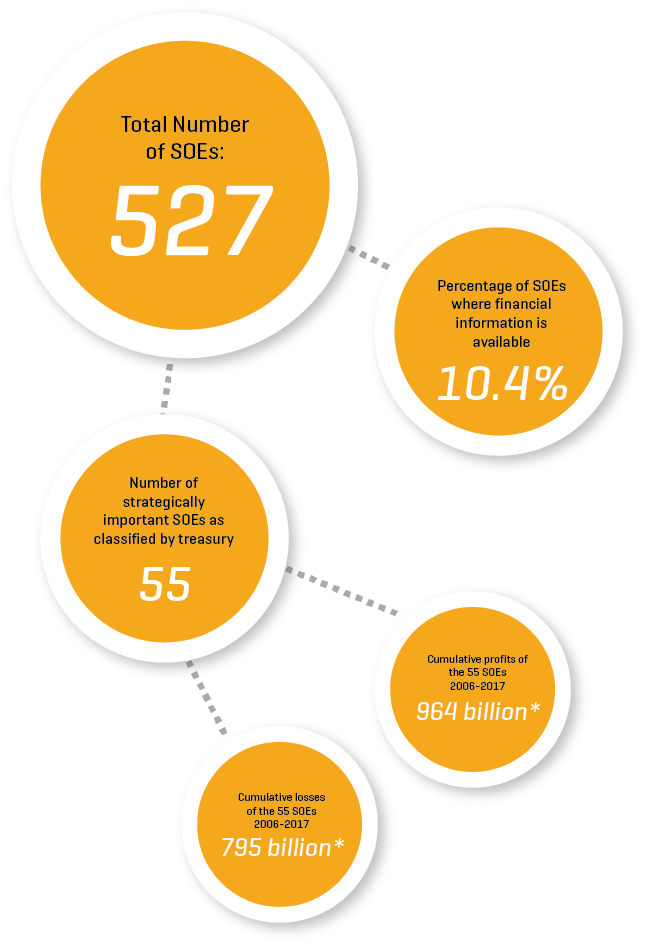

To take a few simple examples; of the 55 large SOEs only ten had published an annual report for 2016, as per the 2017 report of the department of Public Enterprises. (The law requires publication within six months of the year’s end. Timely disclosure is essential in a robust corporate governance framework as it provide the basis for scrutiny for stakeholders.) Thirty were two or more years in arrears.

Sri Lankan Airlines has suffered a Serious Loss of Capital [2], but the legal procedures that must follow have been ignored. Even the labour laws are not enforced-the JEDB has unpaid EPF liabilities of Rs.323m but earns no sanction.

Therefore, the performance of SOEs suffers from both political costs (i.e. the costs associated with control of firms by politicians who have political goals that differ from economic efficiency) and agency costs (i.e. the costs resulting from managerial pursuit of private benefits at the expense of the firm), leading to chronic inefficiency and underperformance.

Conclusion: a dysfunctional state that serves political interests

The political process incentivises corruption. A weak governance regime means little accountability and few checks on government spending. In addition, limited technical capacity means policy is open to “capture” by special interests. The combination is deeply dysfunctional: a parasitic system that transfers wealth to the politically connected through corruption and rent-seeking.

The weaknesses in the political system are discussed here in order to place the context within which the agency and political costs of SOEs are experienced. Poor oversight magnifies these costs. In combination with the perverse incentives of politicians it gives rise to the blatant breaches of fiduciary responsibility that occur, repeatedly in the COPE reports.

All political systems need to mediate the relationship between private wealth and public power. Those that fail have dysfunctional governments, captured by wealthy interests.

The ramifications of this are far-reaching. Although a full discussion is out of place here, structural weaknesses could explain why a massive expansion in state activity has yielded minimal visible benefits to citizens. Between 2005-15 total government spending quadrupled (from Rs.584 billion to Rs.2,290 billion) with little noticeable improvement in essential services; transport, health, education or waste disposal.

The money is swallowed up in a massive administrative machine. There is endless duplication in the 32 cabinet ministries, 3 non-cabinet ministries, 107 departments, and 24 spending units, 452 SOEs just at the centre. Most developed countries make do with about 20 ministries.

The problem with endemic corruption is that public officials, both bureaucrats and politicians, may redesign programmes and propose projects with few public benefits and many opportunities for private profit.

In Sri Lanka, patronage wins elections which may be why we have 166,588 peons and 25,645 drivers in public service (but only 19,612 medical officers and 32,399 nurses). The public sector workforce ballooned from 850,267 to 1.35m between 2005 and 2016.Salaries and pensions consume almost half of all tax revenue. Much other government expenditure has been funded by debt: but it is only now; when debt is repaid-and taxes rise, that the true cost becomes apparent to the public.

Structural problems require structural solutions; changing the identities of the people who hold public office will not suffice.

A concerted effort to improving oversight is needed, to overcome the resistance from within (as it is not in their interest). The National Audit Bill to strengthen the Auditor General’s role to increase accountability was only passed in July 2018, after being held up since 2003. Requests to open the COPE/COPA hearings to the public by the Committees’ themselves have gone unheeded.

Improving accountability and governance within State Owned Enterprises is important because of the large leakages that take place, but this will address only the subset of a larger problem.

Sri Lankan intellectuals have long placed great faith in government but given the quality of governance the role that the state should play in public life should be reassessed. The governance mechanisms are what ensure that state activity delivers benefits to citizens. A state that exhibits high levels of governance may be trusted to play a larger role, whereas one with weaker governance should only play a smaller role.

Keynes stated the function of government: it should do only what the people could not do at all, not what it could do better than the people. Our objective should be a state that performs a limited and well-defined number of tasks to which it is suited and has the requisite capacity.