Originally appeared on the Daily News

By Aneetha Warusavitarana

The Sri Lankan government is currently in a rather confused state of having lost track of the number of state enterprises it runs.

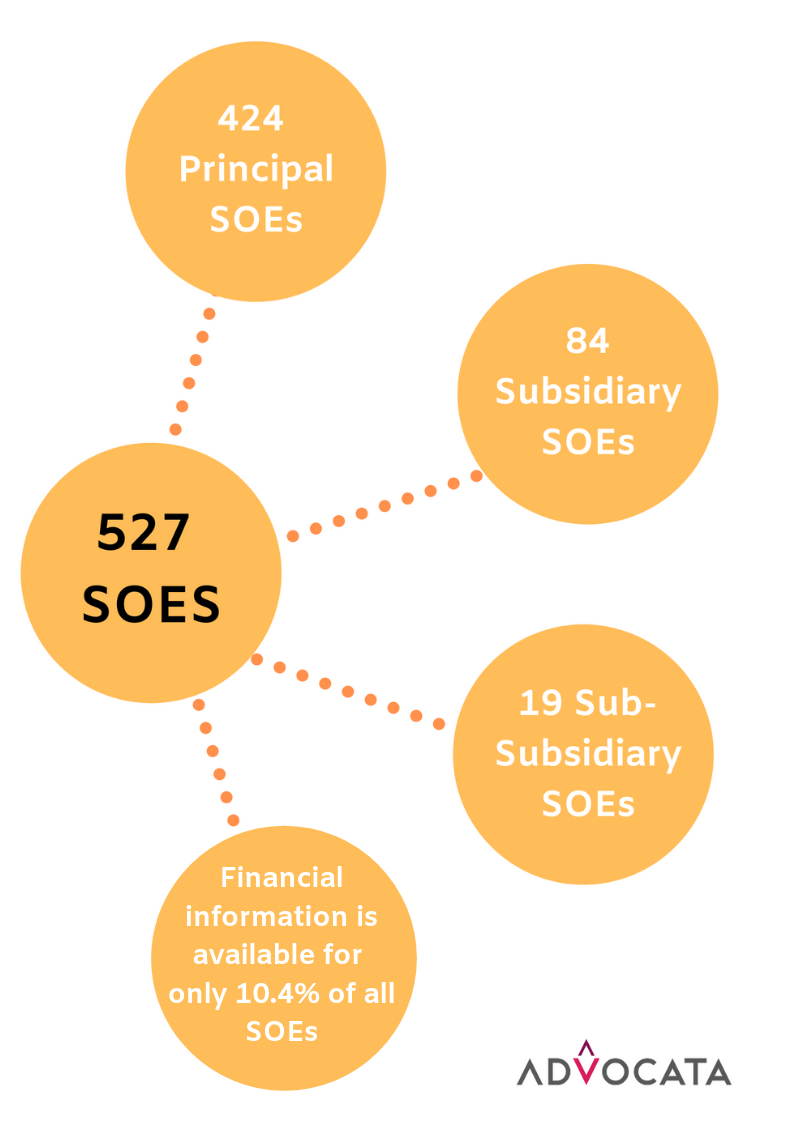

While the Ministry of Finance tracks the financials of 55 key SOEs, the government does not have an official number for the enterprises it runs. The Annual Report of the Ministry of Finance states that there are 400 and this is true to a certain extent. In the Advocata Institute’s 2019 report on the state of state enterprises, it has identified 424 principal SOEs, 84 subsidiary SOEs and 19 sub-subsidiary SOEs; bringing the total to a shocking 527 entities.

While it is bewildering that the government runs a minimum of 527 entities, the losses sustained by these enterprises are a greater cause for concern. When looking at the financials of the 55 strategic SOEs (which account for only 10.4% of the 527), the cumulative losses for the period of 2006 – 2017 amount to a massive Rs. 795 billion.

Reform promises

Apparently, the government has taken note of this. Reform has been promised by a variety of politicians at pivotal political moments. The election manifesto of President Maithripala Sirisena stated,

“I will implement a plan corresponding to Singapore’s Thamasek model to regularise the Management of State owned strategic institutions and sectors such as state banks, the harbour, energy, water supply, airports and transport.”

This is essentially a good starting point. Under the Singaporean Temasek model, one holding company is responsible for countries’ public enterprises. This is a model that has worked, with variations being adopted in other countries.

The Indonesian variation of the model has one holding company for each sector – given that Sri Lanka is a much smaller country it is possible that we could manage with one holding company.

The benefits of adopting this model lie in the accountability it creates. Having a holding company creates distance from the government and its SOEs, reducing chances for political intervention. It’s important to note that the Prime Minister has also expressed his support for this model, which meant the policy had buy-in from both sides of then unity government. While the Temasek model is a step in the right direction, if we want our SOEs to be efficient, privatisation is where the final solution lies.

On that note, the ‘privatisation of state-owned enterprises’ was mentioned early in the 2016 budget speech. The speech highlighted the loss-making nature of SOEs and the negative impact this it had on the budget. The solution mentioned was the use of ‘corrective measures’ to transform SOEs into commercially viable enterprises.

The methods recommended were selective, market-based pricing mechanisms for public utilities, rationalising of recruitment and exploring public-private-partnership opportunities.

The budget speech of 2017 also stated that steps would be taken to make SOEs viable business entities through cost reflective pricing structures and operational autonomy.

It went further, committing to the listing of non-strategic enterprises such as the Hyatt, Grand Oriental Hotel, Waters Edge, West Coast, Manthai Salt, Hambantota Salt and Hilton. The rationale was that the money raised could be used for debt repayment. Notably, both the budget speech of 2018 and 2019 were silent on the topic of SOE reform.

Working under the assumption that these promises were made in good faith, there is the question of why reform never materialises. It is possible that we have been trying to run before we can walk. While SOE losses have to stemmed, it may be better to have smaller, digestible phases of reform than a large reform agenda which will never move beyond a statement or speech.

Reform is vital, but should realistic

A key point highlighted in the recent IMF staff report was the losses sustained by state owned enterprises. Three main SOEs; the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and SriLankan Airlines have recorded a combined loss of 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2018, compared to 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2017. The report also puts the financial obligations of non-financial SOEs at 11.8% of GDP.

Given rising losses and the urgent requirement for some level of action to be taken, it may be that the government should focus on smaller, more achievable reform that lies within the realm of political possibility. In Advocata’s 2019 report on the state of state enterprises, a few key reforms were identified.

These reforms were chosen because they are politically feasible and because they will have a targeted impact on the root causes behind SOE losses. Two of the main reforms are detailed below.

Conduct a survey of all state-owned enterprises: it is impossible for the government to regulate or monitor these entities, when the government is uncertain of the scope of its responsibility. Once the survey is completed, the government can institute basic reporting procedures.

Strengthen COPE, COPA and the Auditor General’s Department: these institutions are the main source of accountability for state-owned enterprises and as such should be given a mandate which allows them to take sufficient action.

Once these steps are taken, the government could expand its reform agenda to encompass the OECD principles of corporate governance, which include clearly defining the state’s role as an owner, establishing an effective legal and regulatory framework for SOEs, ensuring transparency and disclosure, while emphasizing the state’s responsibility to stakeholders. In short, the OECD guidelines will nudge SOEs towards a path of transparency and efficiency.

However, in the short term, the first two reforms mentioned above remain crucial.