In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

Around 20 years ago as I recollect, there was a discussion on Sri Lankan radio about whether it was fair for women to wear trousers or jeans. This was a topic of conversation that was raised at a time when a female president led the country; a country that had produced the first female Prime Minister in the world.

When I was at Colombo University, the topic “Should women wear trousers?” was assigned for a debate during the ragging period. Though we have seen some progress on this topic, the manner in which we, as a society, treat women has not changed drastically.

Walking in the shoes of women is a difficult concept to consider as a man. Today, we can see women voicing out multiple social and economic issues that they have faced. As men, we should be using our privilege to give women a wider platform and have them at the forefront in driving social and economic development.

Women in Sri Lanka are unfortunately often expected to carry the brunt of the care burden, regardless of whether they also engage in paid labour or not. However, what many do not realise is that this is a twofold struggle. Women not only have to balance all this work, but also endure the emotional toll that comes with it. Generally, they find themselves shouldering the logistical burden of co-ordinating and delegating any tasks that they do not take on themselves. This burden is already an unreasonable expectation. Women’s domestic labour should in fact be classified as an unpaid business. However, we are only adding to this problem via high tariffs on items such as LP gas cookers and washing machines. Most women are limited by their domestic labour, and the degree of freedom and choice that they have outside of this often depends completely on the affordability of tools that ease their burden.

The worrying fact is that our economic policy is what limits the freedom of women in many cases. At my previous office, my colleague used to celebrate her mother’s birthday for a week and her celebration was simple each year. She would bring home food for dinner for a week so that her mother would not have to cook dinner during that birthday week. I asked her: “How is not allowing your mom to cook for a week a treat?” She replied: “If you know how painful it is to run a kitchen every day you will realise what a good treat it is to take rest for a week.” I realised that she was absolutely right. Sri Lankan women are giving up their paid jobs in order to take on the domestic burden of their households.

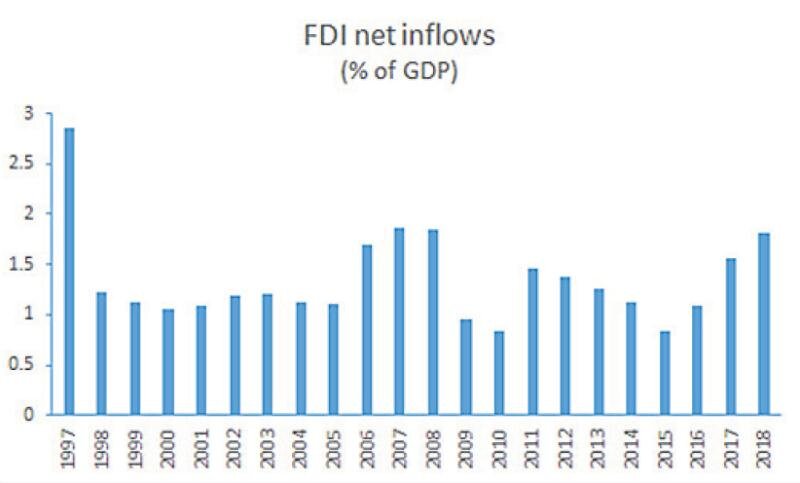

It is no surprise that Sri Lanka’s female labour force participation declined from 41% to 36% from 2010 to 2016 when our economic policy is doing its part to keep women out of the labour force.

The fundamental question we have to ask here is whether our women have truly been given the freedom of choice, or whether this choice is hindered by our policy and social ecosystems. If women wish to choose a career outside of their home, do they actually have the ability to make that choice? This should be a basic right. The conversation on economic rights needs to go hand in hand with that of social rights. How have we set our economic parameters? Let’s take a look at our tariff policy and how it impacts the lives of Sri Lankan women.

High tariffs on household electronics

It was saddening to see the amount of household durables that most Sri Lankan women who work in the Middle East buy at airport duty-free shops. It is a clear indication of the high tax applied on daily household durables such as washing machines and cookers.

Are we not restricting women’s freedom by making these household durables unaffordable for them? According to data by the Department of Census and Statistics, only 20% of all Sri Lankan households use a washing machine. Washing machines might not be within budget for the rest of the 80% of households, but high tariffs are definitely a reason why the numbers of those using washing machines are so low. The time saved from washing clothes could have easily been used for paid external work, limiting the domestic burden that tends to fall on women. This same rationale applies to other household durables such as refrigerators and cookers.

High tariffs on sanitary and childcare products

Another category that is making life more difficult for a woman is unfair taxes on sanitary napkins and baby diapers. As childcare within a household generally falls on women, both of these goods are essential items that need to be purchased. Regarding taxation on sanitary napkins, Advocata’s strong punchline said it all: “‘I love having my period and paying tax on it,’ said no woman ever.” According to research by Advocata, a woman spends approximately Rs. 600 every month, and Sri Lanka has about 4.2 million menstruating women. While the tariffs on sanitary napkins have been reduced, they are still around 52%. It should not be hard for us to walk the talk of empowering women by bringing down the tariff rates on such simple matters. Can we be proud to say, as a country, that we have a 52% tariff rate on our menstruating women?

Surprisingly, baby diapers are also taxed at 52%. This is a double whammy on women. Caring for an infant requires spending a significant amount of time washing kids’ clothes and making them comfortable. Having diapers which are unaffordable is just another hindrance.

I do not have the luxury of space in this column to elaborate further on how we are making women’s basic needs expensive and limiting their freedom; we cannot be proud of the situation that the women in our country are in. They continue to be held to unreasonable expectations, including shouldering the domestic burden within a household. We need to work towards alleviating both the social and economic pressures that women are under. Women deserve the freedom of choice. Women have the ability to engage in paid work if they want to. We need to ensure that women also have an equal opportunity to choose paid work if they want to. So this will be yet another Women’s Day without true freedom for women.