Advocata COO spoke to newsfirst on State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) on the BizFirst program

Ravi Ratnasabapathy on Cabinet re-shuffle and the state of the economy

Advocata fellow Ravi Ratnasabapathy appeared on the Bizfirst program to discuss the recent cabinet reshuffle and the state of the economy in Sri Lanka.

We should privatize the government owned tourism businesses

Cheap footwear imports benefit ordinary Sri Lankans

Sri Lanka's footwear industry has written to the Director General of Customs requesting a crack down on illegal imports of footwear.

The industry claims that Sri Lanka is losing over US $112.5 million annually in foreign exchange as a result of cheap footwear imports from China and India. The industry estimates that the state should have gained revenue of around Rs. 9 billion if proper taxes had been paid on the import shoes

Local manufacturers are supposed to be on the verge of collapse as they cannot compete.

The industry has made repeated calls for protection following the reduction of duties on imported sports shoes in the 2011 budget. Successive governments since 2002 have introduced tariff barriers to protect the local footwear industry but some duties were reduced in 2011.

Shoe makers claim that illegal imports are mainly factory overruns, stock lots and inferior quality products and are available in the market for less than Rs. 750 which is below the minimum total custom tariff on footwear (CESS Rs. 600 +PAL + VAT and NBT). Consumers who were befuddled as to why shoes are so expensive in Sri Lanka now know why.

Yet, only last month the Minister of Industry and Commerce Rishad Bathiudeen, speaking at the Footwear & Leather Fair remarked that Sri Lanka's footwear and leather exports have increased by 28% in 2016. "Our footwear and leather exports in 2016 increased by 28% in comparison to 2015 revenues to $140 Million showing strong growth trends”.

It is clear that the problem is not as straightforward as the industry claims. The local shoe industry seems to succeed competing, at least on some level in the global market. If they compete abroad they should be able to compete in the domestic market, why is there a need for protection?

Let us try to assess the relative benefits and costs of protecting the local shoe industry.

The industry maintains that letting consumers buy cheap imported shoes threatens the jobs of 40,000 people employed in the industry island wide. The producers have requested that the duty structure that prevailing before 2011 be reintroduced. Duty on shoes was 30 per cent or Rs. 1000 per pair whichever was higher. Addition to duty, a CESS of Rs. 500 was levied per pair.

This is a significant additional cost that consumers are burdened with. Additional costs will be a source of particular anguish to the parents of the four million children who attend school and whose shoes would need to be changed almost every year. All children have in common a constant need for new clothes and shoes as they grow. Kitting out youngsters for school can be expensive; those who participate in sports may require several different types of shoes, placing a heavy strain on family budgets.

The effect of import duties is to raise the price of both foreign products and domestic goods. These policies may “save” the 40,000 jobs in the industry, but only at the expense of the overall welfare of consumers. The annual shoe requirement locally is around 40 million pairs; a greater part of the population needs to pay higher prices on shoes in order to support the footwear industry.

Trade protection temporarily helps some producers, but it cannot do this without harming others. Who is affected by higher import duties? First consumers who either buy an imported shoe or a local shoe sold at a high price. Remember it is not just a case of an imported shoe being sold at a high price and consumers turning to local shoes instead. The purpose of the duty is to enable local products to be sold at higher prices (benefiting manufacturers) than would otherwise be possible.

Since they pay higher prices, consumers would have less money to spend on other goods, indirectly hurting various other trades. Due to high prices people will buy less; they will manage with broken or worn out shoes without replacement. Shoe traders and retailers, who sell imported shoes, will also suffer from reduced business.

Various arguments are put forth to support protectionism; to protect sunrise (infant) industries, sunset (declining) industries, strategic industries (energy, water, food etc.), save jobs or deter unfair competition.

When firms within certain industries call for protection, for whatever reason, policymakers must view the issue from the perspective of the consumers as well and weight the relative merits of the claim. Consumers do not form associations and lobby for their interests, unlike businesses, so Governments are under little pressure to look after consumer interests. Yet, in most instances the number of consumers far outweighs the number of producers or the number of jobs concerned. Often, the real goal of the industry is to gain security through the removal of competition.

Certainly, if duties are lowered, some workers in the footwear industry may lose their jobs and some or all of the firms may be forced to close by the foreign competition. The indsutry claims that 2000 cottage type businesses may have to close.

Workers will have to look for employment elsewhere. However, other job opportunities will be made available since the money that consumers previously had to pay for duties could be used to buy new products or services or consume more of already existing products and services. Employment is created in other sectors because resources will flow to areas that consumers consider being of highest value to them.

It is rather ironic that while the industry focuses on opening markets abroad it is keen to keep the domestic market as protected as possible, in the interest of maximising exports and minimising "harmful" imports. It is fortunate that the export destinations for Sri Lanka's shoes are more open than Sri Lankas' home market.

In general, tariffs promote the production of items in which a nation is inefficient and deter other production lines in which the country has a comparative advantage. By reducing tariffs, things that could be produced more efficiently in one country would be made there and items that could be purchased less expensively abroad would be imported.

In the 1950’s, Britain attempted to protect its famed Lancashire textile industry through restraints on imports. At best, this may have prolonged its decline, but it did nothing stop it. Low-cost textiles were being made on a mass scale by foreign competitors. Eventually the Britain’s textile industry moved to high added value luxury and designer products that sold at a premium in both domestic and foreign markets. Some UK textile products have become world-beaters, without the need for subsidies or tariffs to protect the jobs they sustain.

Some of Sri Lanka’s shoe exporters are already competing effectively in the world market. Reducing import duties on shoes would benefit consumers and would spur the local industry to improve efficiency and towards greater innovation, to the long term advantage of all concerned.

A version of this article previously appeared in the Ceylon Daily News.

Ravi Ratnasabapathy is a Fellow of the Advocata Institute and a management accountant by Training.

Should we have Socio-economic rights in the constitution in Sri Lanka?

A new Constitution is currently in the works and the question has arisen as to whether social and economic rights should be included as was the case with South Africa’s new constitution. No one doubts the importance of access to education, healthcare or shelter, but should these be included within the Constitution?

This was the subject of a talk delivered by Professor Pratap Bhanu Mehta, at a forum organised jointly by the Advocata Institute and Echelon Magazine.

Prof Mehta stated that the most important fact to keep in mind is that a constitution is a social contract among a particular group of people. It has to reflect the historical specificities of those people, their diverse goals, aspirations and identities. It needs to be legitimate in the eyes of the people who will be governed by that constitution.

We can all agree that it is good to have the best healthcare for all citizens, as equitably as possible; nobody would disagree with the need to disseminate education as widely as possible and few would disagree that some sensible labour legislation is necessary.

Will these goals be met by including socio economic rights in the constitution rather than leaving it to the normal hurly burly of representative politics?

Unfortunately, the comparative experience provides no clear answer, it depends on circumstances. There is also a paradox: it is precisely those countries that would have achieved these goals even in the absence of constitutionalising these rights that also do better when they do constitutionalise them.

State failure

Prof Mehta claimed that a part of the fascination with constitutionalising these rights comes from a feeling of deep state failure. Most countries that have achieved these goals, as in Scandinavia or advanced developed countries have done so without constitutionalising them. Therefore, the notion that constitutionalising these rights is a necessary condition for achieving them is false.

He stated, in the developing world there is pressure for constitutionalising these rights because it is believed that in the absence of a justiciable constitution right, the legislature, ministers, parliament, will not create the conditions to achieve these rights.

This context is very important. The discourse on rights in developing countries emerges from a history of state failure. We want to go to court because the legislature does not give us these rights. The paradox is that if we live in a country where the legislature does not deliver these rights, it is highly unlikely to do so even if constitutionalised as the state is unlikely to have the effective institutions to deliver these rights.

The problem is essentially one of governance and the idea that constitutionalising rights can substitute for broad governance reforms needs to be challenged.

The drafters of the Indian constitution drew a distinction between Fundamental Rights which are justiciable under the constitution and the Directive Principles of State Policy which are not. The Directive Principles contain the social and economic rights. While the Directive Principles imposed an obligation upon the State to strive to fulfill them, they are not justiciable rights and their non-compliance cannot be taken as a claim for enforcement against the State.

The rationale for this distinction is that in any society there are deep differences in opinion on economic matters, and a constitution should not prejudge these questions. We can all agree that better healthcare is a good idea, more education is a good idea, more health workers is a good idea, but we might disagree on the institutional architecture to deliver these rights.

Deep entrenchment of these rights in a constitution framework abridges that democratic and political discussion. The determination of the best solution should emerge from democratic politics and be open to iterative re-balancing, which will occur over time, depending on how the experience unfolds.

To illustrate, Prof Mehta took the example of workplace protection for workers. We may agree that increasing workers power vis a vis employers is a good thing, but we may disagree on the best solution to achieve that outcome.

If one’s economic analysis suggests that a form of social protection detaches income from employment; a minimum basic income, this may lead to a different view as to what the employer-employee relationship should be. From this viewpoint, giving people a minimum basic income may enhance workers bargaining power and may be a better way to achieve the desired outcome than by including stringent minimum wage instructions and placing the onus on the employer.

Thus, we may have two different models of enhancing workers bargaining power. How do we decide which is correct? This is something that should be subject to iterative learning. The danger with constitutionalising is that we may be setting in stone a solution that does not get very far because economic conditions are changing.

Interestingly, in India from the late 1970s the Supreme Court started expanding the guarantee of the Right to Life (a Fundamental Right) to include within it and recognise a whole gamut of social rights; the right to shelter, the right to health, education, right to environment, even a right to sleep.

Education bill

The question to ask is: how far has Indian governance improved as a result of the promulgation of these rights? Prof Mehta admitted that this was a complicated empirical question but his short answer is: only to a very limited extent.

The court pronounced the right to education and India now has a right to education bill as a result, but he claimed this bill was passed the day India’s enrolment in primary education had already reached its goal.

The right came after the fact, and focused largely on the input side of education rather than the output. He claimed that in fact learning outcomes have worsened after that right was promulgated. He said, similar problems existed with the right to environment. How does a country with the most progressive environment laws in the world end up with the filthiest air and the dirtiest water in the world?

Sri Lanka is regarded as one of the most important cases of human development success: it leads South Asia on many indicators, including, universal primary school enrollment, gender parity in school enrollment, under-five mortality, universal provision of reproductive health services, tuberculosis prevalence and death rates, and sanitation. All this, despite the absence of constitutionalised socio economic rights.

These achievements may be traced to enlightened policy and effective administration during the early decades after independence. Nepotism and corruption have rotted Sri Lanka’s public service, a disproportionate share of the budget is spent on defence and debt service, some of which has financed white elephant infrastructure.

Perhaps, these are the real issues to be tackled?

Dr Wignaraja: Can Sri Lanka join Asian Supply chains?

by Dr Wignaraja on Daily Mirror

President Trump’s pledge to put America first during a global trade slowdown has sparked worries that the era of export-led growth has ended. Trade in Asia and globally has slowed since the 2008 global financial crisis but it is not the end of export-led growth. The real issue, however, is whether Sri Lanka can follow East Asia’s success in global supply chains amid slower trade growth and a likely rise in protectionism. Global supply chains refer to the geographical location of stages of production (design, production, marketing and service activities) in a cost-effective manner and linked by trade in intermediate inputs and final goods. For instance, the Toyota Prius—a hybrid electric mid-size hatchback car—for the US market was designed in Japan and is largely assembled there, but some parts and components are made in Southeast Asia and China. Supply chains exist in a wide range of manufacturing and services activities. East Asia’s shift from a poor, less developed agricultural periphery to a wealthy global factory over the last half a century is an economic miracle. The extent of the region’s participation in global supply chains is significantly greater than elsewhere and has spurred East Asia’s global rise to the coveted “Factory Asia” league with the middle-income status for many economies. In 2015, the developing economies in East Asia accounted for 34 percent of global supply chain trade with China making up 15 percent and Southeast Asia for 7 percent. This compares with 34 percent for the European Union, 10 percent for the United States and 5 percent for Japan. However, South Asia is a relatively small player. India accounts for 1.7 percent of global supply chain trade and the rest of South Asia, including Sri Lanka, for 0.13 percent. Structural transformation and rising wages in China have encouraged an outward shift of labour-intensive segments of supply chains ranging from clothing to electronics. Sri Lanka has the potential to attract such supply chains from China. It is strategically located on the way to Europe, offers low wages with reasonable labour productivity and has a dynamic clothing industry. Close proximity to the large Indian market, which is a magnet for Chinese outward investment, is another advantage. Smart business strategies and market-friendly national policies have supported East Asia’s achievement in supply chains. Being a big firm naturally creates advantages to participating in supply chains due to a larger scale of production, better access to technology from abroad and the ability to spend more on marketing. It is crucial for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to work with large firms. Hence, smart business strategies, such as mergers, acquisitions and forming business alliances with multinationals or large local business houses are all rational approaches, as is investing in domestic technological capabilities to achieve international standards of price, quality and delivery. East Asia’s experience suggests that nimble SMEs can also join supply chains by locating to industrial clusters and reap the benefits of interdependence such as co-financing a training centre or a technical consultant to upgrade skills. Business associations can facilitate clustering by mitigating trust deficits to cooperation among SMEs and by coordinating collective actions for cluster formation. For instance, major industrial clusters are visible in Viet Nam near Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, where large firms are surrounded by thousands of SME suppliers and subcontractors making garments, agricultural machinery and electronics goods. Turning to national policies in East Asia, modern cost-competitive infrastructure is crucial for supply chains. This means investing in world-class ports, roads to ports, logistics, electricity supply and information technology infrastructure. Maintaining open trade and investment regimes which encourage investment and transmit price signals to business are likewise important, as well as sound financial systems which emphasize competition among commercial banks and financial inclusion. High-quality, affordable technical and marketing support services and investing in education to develop skilled labour both help SMEs join supply chains. More controversial is the use of industrial policies in East Asia to target credit and subsidies to particular sectors or firms. Some oft-cited examples of failures include Korea’s heavy and chemical industry push, Malaysia’s national car project (the Proton) and China’s home-grown 3G mobile technology TD-SCDMA. More research is needed on good practices, as there is a high risk of government failure and cronyism associated with industrial policies. Joining supply chains will boost industrialization, jobs and incomes in Sri Lanka. There is no one-size-fits-all approach for Sri Lankan firms to join supply chains. Smart business strategies, facilitating business associations and market-friendly policies are all useful ingredients, while business and government collaboration is essential to tailor these ingredients to national circumstances. (Ganeshan Wignaraja is Advisor in the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department of the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The views expressed here are solely the author’s own and do not represent the position of the ADB. This is a guest article for the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce ‘Trade Intelligence for the Private Sector’ (TIPS) initiative that helps its member businesses be up-to-date on new developments in international trade. For more on the subject of this article, refer Production Networks and Enterprises in East Asia an edited volume by G. Wignaraja (2016))

In 2017, the government must deliver on Reforms

By Ravi Ratanasabapathy

First published on the Daily News

Sri Lanka's coalition Government has now been in office for two years; the new president was elected two years ago and the new coalition in Parliament was formed some eight months later. How has it fared, particularly in the sphere of economics?

To put things in proper perspective we must appreciate the unique political moment in which the new administration operates. The change of regime was a shock and expectations soared; perhaps to levels that were unrealistic. The disappointment has now set in as the coalition Government, made up of disparate parties with different agendas unexpectedly propelled to power has grappled with a Gordian knot of issues.

Economic liberalism, good governance, ethnic reconciliation and a sensible foreign policy were expected to materialise overnight. While significant strides have been made they have fallen short of public expectations.

Careful handling

On the economic front in particular expectations have proved to be far too high. The Government has treaded very cautiously, shying away from tackling unpopular reforms and unravelling the web of protectionist regulation that grew up around many sectors of the economy under the 'import substitution' label.

Part of the problem has been in the communication, the public were not aware of the precarious state of the finances that the new Government inherited.

The IMF, in its review in September 2014, noted that "public debt and debt service remain high by international comparison, reserves are limited, tax revenues are low, and medium-term sustainability depends heavily on continued growth and a positive external environment." In 2014 the debt/GDP ratio stood at 75% and debt service costs accounted for 90% of Government revenue. Interest cost alone amounted to 37% of Government revenue.

Despite the bleak economic situation, prompted by forthcoming parliamentary elections in August 2015, the new Government announced a wave of populist measures -increases in salaries, subsidies and reduced fuel costs, amongst others.

These were probably necessary to win the election. Flush from electoral victory the new regime may not even have realised the full depth of the problem they were dealing with: there were periodic news reports announcing various apparently unrecorded liabilities being unearthed during their first few months in office. Unfortunately having won the election, the Government was unable to roll back any of the giveaways or make any headway in reducing the size of the state. Politically expedient but economically unsustainable the resulting fiscal, balance of payments crisis and IMF bailout were inevitable.

Tough measures followed in the budget of November 2016. Personal and corporate income taxes were increased along with VAT and taxes on alcohol and tobacco. Though unpopular these should provide the macro-economic stability within which the Government can embark on a serious programme of reforms. The time for proper reform is now upon us. Eminent economist, Professor Razeen Sally warned that Sri Lanka is in a period of dangerous policy drift and that the window of opportunity for economic was narrowing and that Sri Lanka should not 'miss the bus'.

What needs to be done?

Now that the tax rates have been raised to a level where the fiscal deficit is under control for the moment, it must be secured for the medium term. This means that the State must keep its expenditure under control; no more populist unfunded giveaways, a freeze on recruitment and a general economy drive eschewing extravagance, the elimination corruption and waste through increased transparency and open processes.

This must be followed by measures to start trimming the state. There is some public support for privatisation in a few sectors at least. The government should push ahead with these and list the entities on the stock exchange. The formula used in privatisation during the1980's: sale of a majority stake, a public listing for 20% of the shares with 10% of the equity given free to employees proved to be both popular and successful. It will also give a boost to the flagging stock market and send an important signal to investors that Sri Lanka is ready for business.

Improving the business climate

Some measures have already been announced, which is welcome, but more needs to be done. There is still a need to cut red tape: business regulations must be simplified, the number of approvals for investment minimised and these should be processed by a genuine one-stop-shop rather than a multitude of ministries, and despatched in a matter of days and weeks rather than months. Digitisation and reducing bureaucratic discretion are the way to go.

This in turn will lay the foundation for the big reform which is to reorient policy towards FDI and exports. The trade and FDI regime needs to be liberalised: import tariffs minimised, customs procedures simplified, non- tariff barriers to imports such as quotas/licensing arrangements should be abolished as far as practicable.

If implemented properly, the reforms should take Sri Lanka back on a path of sustainable growth resulting in improved livelihoods for its citizens.

The overall conclusion on the economy over the past two years is similar to contemplating a glass; half full or half empty, depending on perspective. The government has the opportunity to change this perspective to one of near full, provided the moment is seized and a reform programme moves ahead without delay.

What would President-Elect Trump mean for Sri Lanka and Asia?

By D.A Jayamanne

First Published in Daily News

Foreign policy analysts are scrambling to understand the potential impact of a Trump Presidency on Asia and other regions. Not only did Trump ran an unconventional campaign, his campaign themes challenged years of bipartisan consensus on U.S. engagement and leadership in the world. “We will no longer surrender this country to the false song of globalism” said the now President-elect Trump in a landmark speech on foreign policy back in April. He went on to say that a top policy goal in a Trump administration would be to “end the era of [global] nation-building and create a new foreign policy”.

Throughout the campaign Trump was sharply critical of U.S. interventions overseas, especially the war in Iraq, interventions in Libya, even challenging U.S. commitments towards NATO and other U.S. allies.

We don’t know how much of Trump’s rhetoric will translate into policy” says Frank Lavin, a former U.S. ambassador to Singapore and a U.S - Asia expert.

“We don’t to what extent this was just campaign talk or how deep and heartfelt this view is”. Speaking in the online podcast series for Advocata Institute, a Colombo-based think tank, Lavin went on to explain that President elect Trump’s key cabinet positions might provide the first clues as to how the president-elect might govern.

“The eyes of the world would be on him as he selects the key cabinet positions of Secretary of State, Defence and Treasury” says Lavin, “How orthodox are some of these selections; Is he picking from the mainstream currents of U.S. policy engagement, where there is generally a consensus on U.S. leadership in the world, or is he picking more outliers?”. Even then, there could be some ebb and flow warns Lavin, and that it’s wise to adopt a “wait and see” approach until President Trump takes office and gets about his business.

So far, Trump has made several picks that gives hope to the more mainstream sections of the U.S. policy establishment.

This has included picking ex Trump critics such as Louisiana governor Nikki Haley, as the new U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. More surprisingly, it is reported that the president-elect is seriously considering former governor Mitt Romney for the key position of Secretary of State, the U.S. equivalent of foreign minister.

Romney was a fierce critic of Trump’s candidacy and remained bitterly opposed to his campaign till the end. All picks must go through a hearing process before being confirmed.

“Every president wants to put their stamp on the office” comments Lavin, “but I would say there’s there tend to be a lot more continuity in U.S. foreign policy than there is change. Even though President Trump comes into office as a ‘change candidate’. Certainly, some changes may be afoot. Broadly speaking however, United States is the same country and we have the same challenges, our national interests are still the same, so we are probably talking about what kind of weight we are giving to certain foreign policy goals, rather than seeing radical changes to those goals”.

This may be particularly true in the case of U.S. policy towards Middle-powers and smaller countries that doesn’t have a strong policy dimension according to Lavin. These relationships are mostly friendly and revolves around classical diplomacy.

More is known however about Trump’s apprehensions towards multilateral Trade deals. Trump last week doubled down on a campaign pledge to scrap the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a Free Trade deal that involved 12 pacific rim countries including Japan, Canada, Australia and America.

“The TPP would have allowed the U.S. to set the architecture for the Asian region and help determine the kind of trade relations that benefit all parties.” says Frank Lavin, who served as the U.S. under secretary for International Trade from 2005-2007. “If the U.S. is not going to set that architecture, then what we are allowing is for other parties to do it. Some might do it with the U.S. in mind, others might do it to exclude America”.

According to analysts, one of the foreign policy objectives of the TPP was to create trading bloc that counter balances China’s dominant exporting power. American politicians often complain about China’s mercantilist attitudes towards trade. Lavin agrees.

“China can be mercantilist in trade. They do have national champions they promote, and use industrial policy to favor those champions”. But part of the solution is to work more with countries that do play by the rules says Lavin, and this is where the TPP would have been useful according to the former diplomat, who now heads an e-commerce company based in China.

So how does all of this impact Sri Lanka? On trade, the scrapping of the TPP would mean that Sri Lanka is saved from potential risks arising from being excluded in the agreement.

A study by the IPS estimated that Sri Lanka could stand to lose around $40 million worth of exports by being excluded from the TPP. For his part, Trump says that instead of the TPP, he will negotiate “fair, bilateral trade deals” indicating perhaps that a potential U.S. - Sri Lanka bilateral trade agreement may not totally be off the table.

On general foreign relations, things are much murkier. Sri Lanka’s relationship globally is dominated by the alleged human rights abuses during the conflict years and the commitments the country had made to the international community.

Whilst Trump’s campaign rhetoric certainly point to a more non interventionist foreign policy agenda for America, it is unlikely that the entire machinery of U.S. diplomacy be overturned.

As ambassador Lavin explains, critical clues will in be who Trump chooses as his key advisors on foreign affairs, and after that, we’ll just have to wait and see.

On the Budget 2017 : Towards better economic and Fiscal Policy

The Daily News published parts of Advocata's statement on the Sri Lankan naitonal Budget 2017.

The immediate policy priority should be to restore emphasis on exports: Liberalise the trade and investment framework to attract FDI.

Public sector reforms to cut costs are vital. While tax increases may be unavoidable, the additional burden on the public must be minimised: Reforms for the public sector to reduce its size, cut corruption and improve efficiency are essential.

The current tax structure is incoherent and chaotic. It must be reviewed and policy grounded on sound fiscal and tax principles including fiscal adequacy, administrative feasibility, simplicity, transparency and stability.

Despite a significant improvement in the first half of the year, meeting Sri Lanka’s budget deficit for 2016 will be challenging. A significant amount of fiscal consolidation will still be needed over the next few years if the government is to achieve its stated goal of reducing the budget deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020 or indeed meet its commitments to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is likely to create considerable uncertainty over the likelihood of further tax increases.

Given the difficult environment and ambitious targets, the government may be tempted to resort to ad hoc, short-term measures to deal with fiscal crises as they arise, creating a volatile business environment, eroding confidence and leading to a lack of predictability in revenue targets. This, in turn, results in further ‘quick fixes’.

This is a vicious cycle that must be broken if consistency and predictability is to be restored to the tax system. This is possible if the government adopts a framework of evidence-based policymaking, and we urge that this be done as a matter of priority.

Making policy that is based on evidence is not easy, but it is possible to draw on the experience of countries such as the UK, which have adopted such an approach. Frameworks that governments can follow to build and support a system of evidence-based policymaking are available, and the government should seek specialised assistance to implement a structured approach. This will help ensure consistency and predictability in policy, improving business confidence.

Policy making must be an ongoing process, and consultation and assessment should not be limited to a period a few weeks before the budget. Poorly researched policy may cause unintended consequences and result in policy reversals. While all suggestions must be considered, many are likely to come from sectors seeking privileges. These must be carefully researched, subjected to wider consultation and adopted only if overall benefits to society outweigh costs. Some of the complexity and anomalies in the tax code may be traced to the accommodation of various special interest groups.

In achieving its fiscal targets, the government cannot limit its focus to raising taxes. Breaking from the pattern of the past, equal or even greater emphasis must be placed on the reduction of expenditure, reviewing not only the scale of spending but also the scope of the government.

An economy drive eschewing extravagance, the elimination of corruption and waste through increased transparency, and open processes must necessarily form a part of this exercise. Sri Lanka’s leaders frequently cite the example of Singapore. Fiscal prudence has been a hallmark of Singapore’s governing philosophy and successful management of the economy – an ethos that must become a watchword for Sri Lanka’s rulers. The Singapore Civil Service’s “Cut Waste Panel” and “Economy Drive” offer useful practical lessons in managing costs and could be adapted for Sri Lanka.

The tax system must be simplified, widening the base and increasing compliance. The finance minister’s commitment to this is laudable. The remainder of this submission seeks to outline a few key issues and offer avenues for the administration to explore. We believe these ideas are worthy of careful study and could yield outcomes that will assist in stimulating growth, reducing the budget deficit, and simplifying and rationalising the tax system.

Rethink the development strategy

Restore policy emphasis on exports

Lacking a large domestic market and possessing few natural resources, exports offer the best opportunity for rapid development.

Successful integration of the manufacturing sector into global production networks has played a key role in employment generation and poverty reduction in China and other high-performing East Asian countries.

The market-oriented policy reforms of 1977/8 were based on this rationale and served the country well, resulting in a notable diversification of the commodity composition of Sri Lanka’s exports and a consistent improvement in share of world manufacturing exports until the late 1990’s.

However, protectionist pressures began to build in 2001, and from 2004, the relatively open trade policies of the past were explicitly and systematically reversed. A policy paper by the World Bank titled “Increase in Protectionism and Its Impact on Sri Lanka’s Performance in Global Markets” shows that, today, through the proliferation of a variety of para-tariffs, Sri Lanka’s tariff policies are just as protective as they had been more than 20 years earlier.

The present protectionist import tax structure has serious costs for Sri Lanka’s economic welfare and growth; Sri Lanka’s exports relative to GDP have declined, as has its share of world exports. Sri Lanka has fallen significantly behind its competitors. Vietnam, which was on par with Sri Lankan exports in 1990 with $2 billion per annum, today exports $162 billion versus Sri Lanka’s $10.5 billion.

A bulk of Vietnam’s exports is driven by foreign investment and a globally competitive agriculture sector that emerged in the wake of a liberalisation drive that moved away from ‘self-sufficiency’. FDI firms account for 71% of Vietnam’s and 44% of China’s exports. The lesson is clear: To boost growth and create productive employment, Sri Lanka should cut barriers to trade and investment, and focus on attracting export-oriented FDI.

The most important reforms needed are listed as follows:

1. Trade policy reforms: Move from the present chaotic tariff structure towards a transparent, uniform tariff structure

• Unify the existing Customs duty and the plethora of para-tariffs (PAL, VAT, CESS, Customs Surcharge) into a single Customs duty at the individual Customs code level, and then reduce Customs duties across the board to a uniform nominal rate of 15%. Moving towards a low, uniform tariff structure has the potential to increase tariff revenues. This would speed up Customs clearance and reduce the potential for corruption as it reduces the discretion of Customs officials and makes the trade regime predictable.

• On the export side, remove all cess as it reduces the effective price received by exporters, and thereby discourages exports. There is no evidence to suggest that these cesses promote local downstream processing of primary products that are now exported in ‘raw’ (unprocessed) form.

• Join the Information Technology Agreement of the WTO to create free trade in electronics, which will attract FDI to this sector.

2. Foreign direct investment reforms

• Restore the role of the Board of Investment as the ‘one-stop shop’ for investment approval/promotion (as envisaged in the BOI charter). This requires repealing the Revival of Underperforming Enterprises and Underutilized Assets Act (2011) and the Strategic Development Projects Act (2011), or passing new legislation to supersede these two acts.

• It is, of course, necessary to rationalise the fiscal incentives offered to investors, but there is a strong case for providing export-oriented foreign investors with time-bound tax holidays and investment tax allowances beyond the tax holiday period.

There is evidence that tax incentives play an important role in influencing location decisions of export-oriented (efficiency-seeking) FDI, especially where competing countries still offer them, provided of course that the other preconditions are ‘reasonably’ met. (The evidence used in recent policy reports by the World Bank to argue against tax incentives comes from studies that have not made a distinction between ‘market seeking’ and ‘export-oriented’ FDI). Removing all tax incentives, while other negatives continue to weigh on the overall competitiveness in investment and trade, may be counterproductive.

• Sri Lanka has to improve property rights to draw investment. The guarantee against nationalisation of foreign assets without compensation provided under the Article 157 of the present Constitution needs to be maintained under the ongoing constitutional reforms.

• Avoid the current practice of ‘domestic value added’ [which is defined as per unit of domestic retained value (wages + profit + domestically procured intermediate inputs) as a percentage of growth output] as an evaluation criteria in approving investment projects.

Advocata's submission for the Budget 2017

THINK TANK ADVOCATA IS PROPOSING LOWER TRADE TAXES AND TRIMMING PUBLIC SECTOR EXPENDITURE IN ITS RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BUDGET 2017 PRESENTED TO THE MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND PLANNING

Summary recommendations

1. The immediate policy priority should be to restore emphasis on exports: Liberalise the trade and investment framework to attract FDI.

2. Public sector reforms to cut costs are vital. While tax increases may be unavoidable, the additional burden on the public must be minimised: Reforms for the public sector to reduce its size, cut corruption and improve efficiency are essential.

3. The current tax structure is incoherent and chaotic. It must be reviewed and policy grounded on sound fiscal and tax principles including fiscal adequacy, administrative feasibility, simplicity, transparency and stability.

Despite a significant improvement in the first half of the year, meeting Sri Lanka’s budget deficit for 2016 will be challenging. A significant amount of fiscal consolidation will still be needed over the next few years if the government is to achieve its stated goal of reducing the budget deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020 or indeed meet its commitments to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is likely to create considerable uncertainty over the likelihood of further tax increases.

Given the difficult environment and ambitious targets, the government may be tempted to resort to ad hoc, short-term measures to deal with fiscal crises as they arise, creating a volatile business environment, eroding confidence and leading to a lack of predictability in revenue targets. This, in turn, results in further ‘quick fixes’.

This is a vicious cycle that must be broken if consistency and predictability is to be restored to the tax system. This is possible if the government adopts a framework of evidence-based policymaking, and we urge that this be done as a matter of priority.

Making policy that is based on evidence is not easy, but it is possible to draw on the experience of countries such as the UK, which have adopted such an approach. Frameworks that governments can follow to build and support a system of evidence-based policymaking are available, and the government should seek specialised assistance to implement a structured approach. This will help ensure consistency and predictability in policy, improving business confidence.

Policy making must be an ongoing process, and consultation and assessment should not be limited to a period a few weeks before the budget. Poorly researched policy may cause unintended consequences and result in policy reversals. While all suggestions must be considered, many are likely to come from sectors seeking privileges. These must be carefully researched, subjected to wider consultation and adopted only if overall benefits to society outweigh costs. Some of the complexity and anomalies in the tax code may be traced to the accommodation of various special interest groups.

In achieving its fiscal targets, the government cannot limit its focus to raising taxes. Breaking from the pattern of the past, equal or even greater emphasis must be placed on the reduction of expenditure, reviewing not only the scale of spending but also the scope of the government.

An economy drive eschewing extravagance, the elimination of corruption and waste through increased transparency, and open processes must necessarily form a part of this exercise. Sri Lanka’s leaders frequently cite the example of Singapore. Fiscal prudence has been a hallmark of Singapore’s governing philosophy and successful management of the economy – an ethos that must become a watchword for Sri Lanka’s rulers. The Singapore Civil Service’s “Cut Waste Panel” and “Economy Drive” offer useful practical lessons in managing costs and could be adapted for Sri Lanka.

The tax system must be simplified, widening the base and increasing compliance. The finance minister’s commitment to this is laudable. The remainder of this submission seeks to outline a few key issues and offer avenues for the administration to explore. We believe these ideas are worthy of careful study and could yield outcomes that will assist in stimulating growth, reducing the budget deficit, and simplifying and rationalising the tax system.

RETHINK THE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

Restore policy emphasis on exports

Lacking a large domestic market and possessing few natural resources, exports offer the best opportunity for rapid development.

Successful integration of the manufacturing sector into global production networks has played a key role in employment generation and poverty reduction in China and other high-performing East Asian countries.

The market-oriented policy reforms of 1977/8 were based on this rationale and served the country well, resulting in a notable diversification of the commodity composition of Sri Lanka’s exports and a consistent improvement in share of world manufacturing exports until the late 1990’s.

However, protectionist pressures began to build in 2001, and from 2004, the relatively open trade policies of the past were explicitly and systematically reversed. A policy paper by the World Bank titled “Increase in Protectionism and Its Impact on Sri Lanka’s Performance in Global Markets” shows that, today, through the proliferation of a variety of para-tariffs, Sri Lanka’s tariff policies are just as protective as they had been more than 20 years earlier.

The present protectionist import tax structure has serious costs for Sri Lanka’s economic welfare and growth; Sri Lanka’s exports relative to GDP have declined, as has its share of world exports. Sri Lanka has fallen significantly behind its competitors. Vietnam, which was on par with Sri Lankan exports in 1990 with $2 billion per annum, today exports $162 billion versus Sri Lanka’s $10.5 billion.

A bulk of Vietnam’s exports is driven by foreign investment and a globally competitive agriculture sector that emerged in the wake of a liberalisation drive that moved away from ‘self-sufficiency’. FDI firms account for 71% of Vietnam’s and 44% of China’s exports. The lesson is clear: To boost growth and create productive employment, Sri Lanka should cut barriers to trade and investment, and focus on attracting export-oriented FDI.

The most important reforms needed are listed as follows:

1.Trade policy reforms: Move from the present chaotic tariff structure towards a transparent, uniform tariff structure

• Unify the existing Customs duty and the plethora of para-tariffs (PAL, VAT, CESS, Customs Surcharge) into a single Customs duty at the individual Customs code level, and then reduce Customs duties across the board to a uniform nominal rate of 15%. Moving towards a low, uniform tariff structure has the potential to increase tariff revenues. This would speed up Customs clearance and reduce the potential for corruption as it reduces the discretion of Customs officials and makes the trade regime predictable.

• On the export side, remove all cess as it reduces the effective price received by exporters, and thereby discourages exports. There is no evidence to suggest that these cesses promote local downstream processing of primary products that are now exported in ‘raw’ (unprocessed) form.

• Join the Information Technology Agreement of the WTO to create free trade in electronics, which will attract FDI to this sector.

2. Foreign direct investment reforms

• Restore the role of the Board of Investment as the ‘one-stop shop’ for investment approval/promotion (as envisaged in the BOI charter). This requires repealing the Revival of Underperforming Enterprises and Underutilized Assets Act (2011) and the Strategic Development Projects Act (2011), or passing new legislation to supersede these two acts.

• It is, of course, necessary to rationalise the fiscal incentives offered to investors, but there is a strong case for providing export-oriented foreign investors with time-bound tax holidays and investment tax allowances beyond the tax holiday period. There is evidence that tax incentives play an important role in influencing location decisions of export-oriented (efficiency-seeking) FDI, especially where competing countries still offer them, provided of course that the other preconditions are ‘reasonably’ met. (The evidence used in recent policy reports by the World Bank to argue against tax incentives comes from studies that have not made a distinction between ‘market seeking’ and ‘export-oriented’ FDI). Removing all tax incentives, while other negatives continue to weigh on the overall competitiveness in investment and trade, may be counterproductive.

• Sri Lanka has to improve property rights to draw investment. The guarantee against nationalisation of foreign assets without compensation provided under the Article 157 of the present Constitution needs to be maintained under the ongoing constitutional reforms.

• Avoid the current practice of ‘domestic value added’ [which is defined as per unit of domestic retained value (wages + profit + domestically procured intermediate inputs) as a percentage of growth output] as an evaluation criteria in approving investment projects.

The very nature of the ongoing process of global production sharing (production fragmentation) is that per unit value added of production plants located in a given country within vertically integrated global industries (such as electronics and electrical goods) is usually very thin. The contribution of such production to domestic output (GDP) depends on the volume factor and the ability to produce for the vast global market, not on per unit value added.

In some traditional industries that use diffused technology (such as garments, footwear, travel goods), there is opportunity to increase per unit value added by forging backward linkages, but this is a time-dependent process and depends on export volume expansion. In the garment industry, per unit value added was around 20% at the beginning, but is now over 60%. Backward-linked knitted textile production and other ancillary input industries (hangers, buttons, labels, packaging material) have emerged as the volume of export expanded, creating sizeable demand for such inputs.

3. Macroeconomic policy

Trade, investment and labour market reforms need to be accompanied/complemented by macroeconomic policies to regain international competitiveness of the economy. Relying solely on nominal exchange rate depreciation for this purpose is not advisable, given the massive build-up of foreign-currency denominated government debt. Also, given the increased exposure of the economy to global capital markets, large abrupt changes in the exchange rate could shatter investor confidence, triggering capital outflows.

What is required is a comprehensive policy package encompassing some exchange rate flexibility and fiscal consolidation, which requires both rationalisation of expenditure and widening of the revenue base.

The current import-substitution policy retards growth and hurts consumers.

The present policy stance and import tax structure have drawn capital, labour and land to high cost, and highly protected import substitution farming and agricultural processing activities with low or negative economic rates of return. Sri Lanka’s food prices are higher than in the region due to high tariffs imposed to achieve self-sufficiency, hurting the poor and possibly contributing to malnutrition particularly of poor children. At a time when the government is burdening people with higher taxes, it is imperative that attempts be made to reduce food costs; revising this policy could contribute significantly to lowering the cost of living.

An example of this policy is rapid growth of maize and soybean cultivation over the last 10 years. These are not traditional crops and were not cultivated on any scale prior to 1998. These are used primarily as raw materials for the production of animal feed. Subjected to heavy protective tariffs, the cost of these locally produced crops are far in excess of world prices and directly related to the high cost of local poultry products. Instead of reviewing a flawed agricultural policy, the government has reacted to high retail prices of poultry by introducing price controls.

The policy of protecting the local sugar industry has had a similar impact and should also be subjected to review. The protective policy toward wheat imports has resulted in increased retail prices of bread, despite a collapse of world wheat prices by 50% since 2013.

The above highlights just a few key issues; there are many others. The government needs to study the impact of its trade and agricultural policies on consumer prices, and review its policies to maximise benefits to society as a whole. The ill effects of poor agricultural policy are not limited to higher prices, and their unintended consequences may extend to the human-elephant conflict and the recent spread of chronic kidney disease. The review of policy needs to be holistic.

PUBLIC SECTOR REFORM

Cumulative public debt and the high budget deficit have been key drivers of macroeconomic instability in Sri Lanka. Higher government borrowing not only wreaks havoc in the government’s finances, but also crowds-out private investment by pushing up interest rates. Sri Lanka also operates a “Mega State” apparatus, with a massive public sector, unproductive/loss-making state enterprises and an oversized peacetime military that further diminishes the fiscal position.

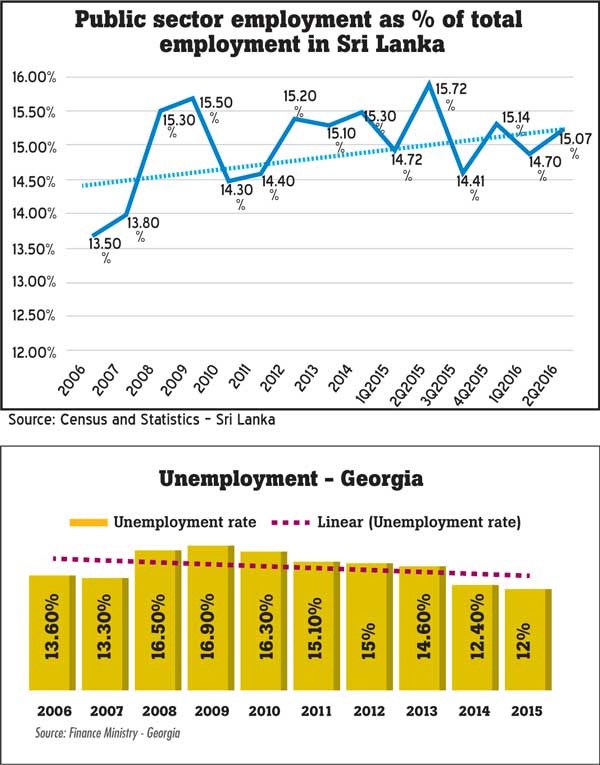

The massive increase in public sector employees starting from about 850,000 in 2005 to around 1.27 million by 2016 also has knock-on effects on the political economy, with both major parties now having to pay homage to this large voting bloc by promising unfunded and unsustainable goodies such as salary increases and other benefits – what analysts term ‘an auction of non-existent resources’ – at each election.

While most commentators emphasize enlarging the tax net to address fiscal imbalances, Advocata believes that reducing the size and scope of the state is more pressing. While political space for reforms may be limited, public opinion is increasingly skeptical of loss-making state enterprises, which is an argument reformists in government could use.

Advocata urges policymakers to look into following avenues of reform:

Addressing the debt burden

The government’s debt/GDP ratio is 75%. Debt service costs (interest and capital) accounted for 90% of government revenue in 2014. The previous year’s debt service cost actually exceeded revenue; the ratio in 2013 was a whopping 102%. Interest cost alone amounted to 37% of government revenue in 2014.

Sri Lanka regularly runs a primary (before interest payments) budget deficit, which means recurring expenditure is being funded by debt, a situation that is clearly unsustainable. Sri Lanka’s debt ratios bear some uncomfortable parallels with those of Greece, just before the outbreak of the debt crisis.

Restructuring the debt to extend its maturity and reduce interest rates could provide some relief, but disposing of unproductive state assets and using the proceeds to reduce debt is a more permanent solution and we offer a few ideas below.

Reforming SOEs

Disposing of loss-making and unproductive state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is a way of easing the debt burden and preventing further deterioration of the fiscal position. The outstanding SOE debt to banks is at Rs757 billion, more than four times what the government spent on health services in 2015. Some SOEs have accumulated so much debt that even privatisation may not be possible. These could simply be shut down with generous severance payments to employees, which will be cheaper in the long run.

Reform of SOEs need not be limited to loss-making enterprises. SOE’s often employ significant resources in terms of labour, land and other factors of production, which could be better utilised. Conducting a comprehensive productivity study would allow the government to determine which ones to shut down, which ones to privatise and which ones could be held under ownership at a government holding company in the model of Singapore’s Temasek Holdings.

Reactivating “Dead Capital”: State-held land

The Land Reform Commission was vested with about 987,000 acres, some of which could be used for more productive purposes. Additionally, government ministries, schools and other facilities occupy prime real estate blocks in major cities like Colombo, which greatly outweighs their economic value.

As an initial step, accounting of property rents at market values would allow the government to get an accurate sense of the value of the dead capital that the government is occupying, which could be put to more productive use. The Colombo Dutch Hospital project and the clearing of the Army headquarters for commercial activity are examples of how dead capital in government-held land could be activated for more productive use. The government should draw up a Land Asset Sales Programme, an orderly and coordinated programme to dispose of surplus or underutilised land. The proceeds from these sales should be used to reduce national debt. The sales programme must be run in an open and transparent manner by an independent body free of political influence to minimise corruption.

Public-private partnerships for infrastructure

Converting existing infrastructure such as highways into Public-Private Partnerships could raise funds to pay down the loans that were used to finance them. Operational rights could be auctioned in a transparent manner to private investors. New infrastructure projects should be on the basis of a Build Own and Operate (BOO) model or Build Operate and Transfer (BOT) model, which has been used successfully all over the world to finance infrastructure projects.

Restoration of the National Procurement Agency (NPA)

The NPA was established in 2004 to streamline procurement, reduce waste and corruption, and ensure better transparency and governance by centralising procurement under an independent body. The agency was believed to have been effective, which lead to it being shut down, allegedly for political reasons, in 2007. Its operation should be revived and its independence guaranteed.

The defence budget

Spending on defence has grown from around Rs144 billion in 2009 to an estimated Rs306 billion in 2016, a massive increase in a time of peace. Due to the politically charged nature of the expenditure, this has been the ‘elephant in the room’. While acknowledging that immediate demobilisation or salary cuts are not feasible, continuous growth in defence expenditure seven years after the end of the war is something that requires questioning.

It is one of the largest items of expenditure, and discussion of this subject must no longer be avoided. Cutbacks in capital expenditure and hardware are necessary. More generally, a national plan to downsize the military should serve the long-term interest of all communities in Sri Lanka.

Voluntary retirement schemes

The state currently employs over a million people and an additional estimated 220,000 workers employed in SOEs. Some analysts put the figures much higher. In total, the public sector accounts for about 15% of the total labour force.

The public sector pensions and salaries bill for 2015 was Rs717 billion, representing 49% of government revenue. The weight of the wage and pension bill has crowded out priority expenditure in education, health and essential infrastructure, and even operational expenditure necessary to enable employees’ effective functioning. Not only do the salaries and entitlements of these workers burden the fiscal position of the government, it also mops up scarce labour from the private sector. By this account, Sri Lanka probably has the largest state sector in the world.

The dependence on excess labour also means that state agencies become reluctant to invest in new technologies or procedures in fear of backlash or simply not knowing where to allocate the labour.

Reforms in this area are not going to be easy, as the 2002 UNP government discovered to its peril. However, the current levels of state sector cadre places a massive strain on the fiscal position.

The government should commission a report on the labour requirement for the state sector. While attrition and a hiring freeze are preferred methods of cadre management, for some sectors and institutions, Voluntary Retirement Schemes (VRS) may be possible. To manage pension liabilities, a new contributory pension scheme should replace the current defined benefit scheme for any new recruits to the public service.

Reform of energy utilities

Sri Lanka’s energy utilities are a source of macroeconomic instability, and reforms to the sector are long overdue. While detailed studies for longer-term reforms must be undertaken as an interim measure, re-introducing the pricing formula for fuel and extending the formula to electricity will prevent large imbalances from building up. For the electricity sector, an immediate move to daylight saving time could reduce night peak load demand by as much as a third, with consequent reduction in thermal energy generation. In Sri Lanka, the discussion is private participation in electricity centres around fixed contract IPPs. In many other countries, however, this model is now considered outdated, the world has moved on to integrated energy markets. A study by the Pathfinder Foundation carried out in 2007 provides a useful starting point for ideas on moving to energy markets.

THE TAX SYSTEM

Recent budget statements by successive governments, including the present one, have not been in keeping with sound principles of taxation. While recognising the unique political moment in which the new administration operates and the politically expedient measures that were taken to create that political moment, continuing to ignore principles of fiscal discipline can only lead to further imbalances.

The following principles serve a guide to sound tax and fiscal policy:

Fiscal adequacy

The overarching objective should be that sources of revenue, taken as a whole, should be sufficient to meet the demands of public expenditure. Revenue should be elastic or capable of expanding or contracting annually in response to variations in public expenditure. Most crucially, any new benefit or relief measures offered must be fully funded. Government finances are in a dire state, they should not be made worse; ill-conceived proposals in the past have contributed to the structural weakness of the fiscal position.

The adoption of a medium-term budget framework to prioritise, present and manage both revenue and expenditure over a multiyear framework is desirable. It can help demonstrate the impact of current and proposed policies over the course of several years, and ultimately achieve better control over public expenditure.

Rules in the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act may be tightened to reinstate budget discipline, and ensure fiscal responsibility and debt sustainability.

Simplicity, administrative feasibility and transparency

Tax laws should be capable of convenient, just and effective administration. Tax codes should be easy for taxpayers to comply with and for governments to administer and enforce. It is far simpler to adjust rates to existing taxes than bring in new types of taxes.

Any changes needed to the tax code should be made with careful consideration of established practices and open hearings. Each tax in the system should be clear and plain to the taxpayer. Disguising tax burdens in complex structures to deceive the public, the preferred approach by politicians in the past, should be avoided. Simplicity will close loopholes for tax evasion, reduce the scope for corruption and minimise administrative costs.

Neutrality

By and large, taxes should neither encourage nor discourage personal or business decisions. The purpose of taxes is to raise needed revenue, not to favour or punish specific industries, activities and products. Minimising tax preferences broadens the tax base, so the government can raise sufficient revenue with lower rates.

Stability

Taxpayers deserve consistency and predictability in the tax code. Governments should avoid enacting temporary tax laws, including tax holidays, amnesties and retrospective changes. The periodic revision of taxes via gazette notifications should be avoided. Put simply, a good tax policy promotes economic growth by focusing on raising revenue in the least distortive manner possible.

Sin taxes need re-thinking

While our proposals are mostly concerned with broad issues of policy, we have made an exception for ‘sin taxes’ because of their importance to the exchequer.

‘Sinful’ items such as alcohol and tobacco have traditionally been taxed heavily and are the second-largest source of tax revenue for the state. A review of these policies could develop their effectiveness and improve collection. The present government, continuing the practices of the past, has now raised taxation to prohibitive levels. This may be counterproductive because, while high taxes do deter consumption, excess taxation may drive consumers to dangerous illicit substances, and support a thriving illegal alcohol and cigarette industry.

The link between higher taxes and substance abuse is that the use of highly hazardous home brews concocted from medicinal drugs, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals also need to be examined.

Both in Sri Lanka and even in developed countries, it is a tendency for lower income groups to consume cigarettes. In Sri Lanka, there is an additional tendency for lower income groups to consume cottage industry products and items like beedies. Further research needs to be done on the link between education and awareness as opposed to the assumption that cigarette and alcohol consumption is merely a function of affordability or a broader lifestyle/environment and an awareness issue.

High taxes on cigarettes have lead to a massive increase in the lightly taxed Beedi industry, as well as expansion in illegal cigarettes. Customs statistics indicate that beedi volumes have risen from 1.1 billion sticks in 2007 to 3.2 billion sticks in 2013, while cigarette volumes declined from 4.6 billion sticks in 2007 to 4.0 billion during the same period.

Studies carried out by the Institute of Policy Studies make a case for rethinking alcohol taxes, principally to move to a structure of taxation by volume, which will increase state revenues while modifying consumption habits.

The government needs to reconsider its policies for the taxation of both alcohol and tobacco in light of all available evidence. Recent experiences in India and Pakistan highlight the problems with outright prohibition.

On PM's economic statement: most important is to liberalize trade and investment

By Ravi Ratanasabapathy

The article first appeared on the Daily News

The Prime Minister’s statement on the economy to parliament on October 27 struck many a right note and has the ingredients to take the country to the goal of doubling per capita income by 2025.

Most important was the promise of reforms to liberalise trade and investment, to attract foreign investment and restore emphasis on exports.

It is important that the sentiments expressed in the Prime Minister’s statement must follow with practical yet bold economic policy reform. A detailed policy document has been promised and would hopefully contain the necessary implementation plans.

The rest of this brief note is aimed at understanding the policy pronouncements in the context of Sri Lanka’s political and socio-economic priorities.

Improving the business and investment climate

The statement promises a lot: simplifying the process of registering a business, getting construction permits, electricity connections and bank credit, registering property, protecting minority investors, the payment of taxes, trading across borders, the enforcement of contracts, the resolution of insolvency and reforming labour laws.

The Prime Minister’s target to bring Sri Lanka into the top 70 countries in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index by 2020 is welcome. Sri Lanka currently languishes at 110 in the index amongst 185 countries and its position has actually dropped by one place under the current administration. Policy reform to increase the ease of doing business is uncontentious and will draw broad political support from across the spectrum.

However the government must be bolder. Whilst ease of doing business has improved in the last few years, Sri Lanka can do much more to expand general economic freedom in the economy. The Fraser Institute, which publishes the annual index of economic freedom ranked Sri Lanka 111 among 160 countries. The index now ranks countries in the region like Nepal higher in terms of economic freedom than Sri Lanka with India only just behind. Beyond just looking at ease of doing business, Sri Lanka should also focus on other aspects of economic freedom including removing of outdated and arbitrary regulation, reversing recent follies such as Soviet-style price controls and truly living up to the promises of liberalising international trade and investment. In this vein, the proposed establishment of a single window for investment approval in the Prime Minister’s speech is a welcome move.

Sri Lanka can emulate, and where necessary adapt, the best practice policies from other countries such as New Zealand and Australia which rank highly in terms of economic freedom

Trade liberalisation: repeal of the Export and Import Control Act

The Government promises to repeal this archaic piece of legislation and replace it with new legislation based on that of Singapore. If implemented in the true spirit of Singapore’s legislation, this would be extremely positive.

Singapore is generally regarded as a free port and the Government only restricts the import of goods seen as posing a threat to health, security, safety and social decency. Around 99% of imports to Singapore are duty-free.

The policy statement makes reference to “a low tax regime”, the lessons from East Asia and other parts of the world is that the tariff regime needs to be low and uniform. This minimises loopholes, corruption and simplifies customs processing. A low uniform rate of duty eliminates disputes with classification and enables documents to be processed on a self-declared basis (with customs only focusing on misstatements of price and quantities) which results in faster, simpler clearing of goods.

While sentiments to keep a low tax regimes are laudable, a commitment for a low uniform tariff policy should be the goal.

State enterprise reforms and financing of infrastructure

The proposed debt/equity swaps of the Mattala Airport and the Hambantota mark an important step towards reducing the Government’s debt burden. The Government should also convert other infrastructure projects such as the highways into PPP projects by auctioning operational rights.

The statement promises investment in infrastructure in logistics to improve connectivity to global supply chains. Whilst we all welcome investments in critical infrastructure, all new projects should be implemented through public private partnerships to prevent further accumulation of public debt.

The report published by the Advocata Institute on “The State of State Enterprises in 2015” shows that the state has over 245 enterprises in its books, of which only a small number actually reported their financial position. The proposed formation of a Public Commercial Enterprise Board to manage SOEs and the creation a Public Wealth Trust, a centralised body to hold the shares in SOEs is therefore timely. Hopefully these mechanisms may prove to be the first step in imposing accepted reporting practices and better management of State enterprises. Sri Lanka can learn from Singapore’s state enterprise holding company Temasek and other experiences around the world.

Additionally, the listing of the shares of SOE’s on the Stock Exchange would also impose discipline in reporting and is something the Government should explore. Minority stakes could be offered to the public which would raise revenue to the state, allow public participation in SOE’s and broad-base the CSE; even while the majority stake is still controlled by the Government.

The recent announcements regarding the closure and amalgamation of Mihin Lanka into SriLankan Airlines is encouraging but the previously announced partial privatisation of the debt-ridden airline has not yet materialised.

The proposed Public Enterprise Commercial Board should be given a wide mandate to restructure and reform SOE’s including assessing the strategic need for such enterprises, the closure of unviable enterprises and to privatise enterprises where there’s enough commercial interest. The new structure will hopefully be just the first step on the long road to improve overall accountability and governance of these state enterprises.

It is unlikely a one size fits all solution would work for reforming all state enterprises in what would inevitably become a politically charged issue. However the public appetite for bold reform in this area is high with the realisation that the cumulative losses over the last ten years amongst the 55 strategically important enterprises amounted to Rs.636 billion.

Some areas of concern: SME’s rural agriculture

Several proposals including the one to expand SME finance through quantitative targets enforced by the Central Bank must be viewed with caution. Dirigiste lending to push bank exposure further to higher-risk sectors may boomerang on lenders, especially public sector banks, resulting in losses. Any difficulties SME’s may face with access to credit need to be examined carefully and appropriate solutions developed in consultation with financiers.

The establishment of rural modernisation boards and agricultural marketing boards will need to be examined more closely. No details are available so the exact role of these bodies is not clear but the current flawed agricultural policies have pushed up food prices for consumers. Sri Lanka’s food prices are the highest in the region and the priority should be to lower the cost of living through appropriate reforms to the sector.

Apart from a few areas of doubt the overall economic statement is broadly in the right direction and if properly implemented could boost growth and improve the welfare and prosperity of Sri Lankans. The government however has a demonstrable problem with policy inconsistency over the last few years, even amongst its own ministries and between Ministers of the same party. Whilst some diversity of opinion is expected from a coalition government, some of the policies enacted in the recent past have run counter to this and other broad policy pronouncement from the Prime Minister.

These broad ideas will hopefully pass the implementation test and we await the publication of the detailed strategy document.

The writer is a Fellow of the Advocata Institute, a fee-market think tank based in Colombo. www.advocata.org

While Sri Lanka slept Georgia was awake!

The article originally appeared on the Daily Mirror

Georgia, a former Soviet state, has lessons for Sri Lanka on political will and economic reform.

If Georgia was a book, then it is surely is one of many pages. Her pages would be full of Caucasus Mountain villages and places like Vardzia, a cave monastery dating back to the 12th century, and the Black Sea beaches. What is in it for us as a nation lies a few pages after: the visionary political and economic reforms done in Georgia during 2004 and 2012.

Being a country at the intersection of Asia and Europe with a 4.4 million population, Georgia offers many lessons to Sri Lanka, where politicians struggle to drive the country forward after nearly seven decades of independence.

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Republic of Georgia had a long walk through darkness until it finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel in 2004. In the 1990s, Georgia was torn apart by a civil war. The country was taken over by corrupt interests. In 2003 however, Georgians fought back. Peaceful protests after a disputed election saw the ouster of President Eduard Shevardnadze and the end of Soviet-backed rule. In the climatic end of the saga, demonstrators stormed a session in parliament with red roses in hand. Georgians remember this as the ‘Rose Revolution’. In the following presidential and parliamentary elections, reformist leader Mikheil Saakashvili came into power kick starting what many analysts consider a small economic miracle in Georgia.

The story has many parallels to Sri Lanka. Today, we have ended our own military conflict of 30 years, yet the future still seems fractured. Hopes for rapid economic reforms to take Sri Lanka to the next level have quickly evaporated. Instead, the government seems to be embroiled in one political crisis after the other. Unlike the Georgian politicians, instead of seizing the momentum of Sri Lanka’s own political revolution, the Sri Lankan leaders could end up squandering the reform movement.

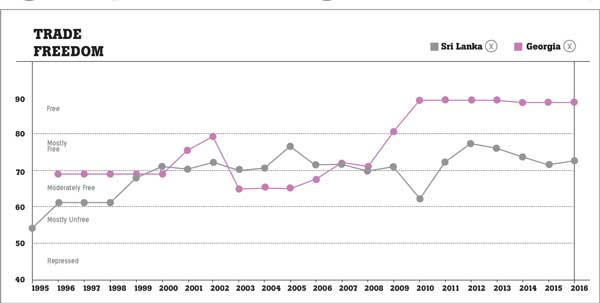

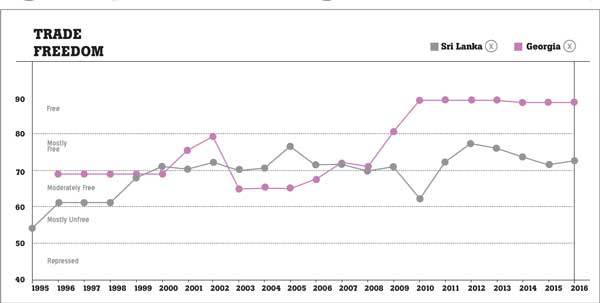

Most economists agree that greater economic freedom has a strong correlation with greater prosperity of a country. Table 1 shows a simple comparison how Georgia, which came to be born a mere 25 years ago, overtook Sri Lanka in such a short span of time.

The Heritage Foundation is one organisation that measures the level of economic freedom in a country. The comparison is telling: (See Table 1)