By Dhananath Fernando

The article originally appeared on the Daily Mirror on May 15, 2016

Would you believe the Sri Lankan government could have declared a Rs. 5000 bonus for each and every citizen in 2016 April New Year if Sri Lankan Airlines even if they had broken even for last 10 years.

The subject is State Owned Enterprises (SOE) and strangely most of them do not have proper financial data (Data is publicly available for 55 out of 255 SOE’s). I am adding my two cents worth to write about the mega losers of public money and some ‘why’ factors for the reader’s consumption.

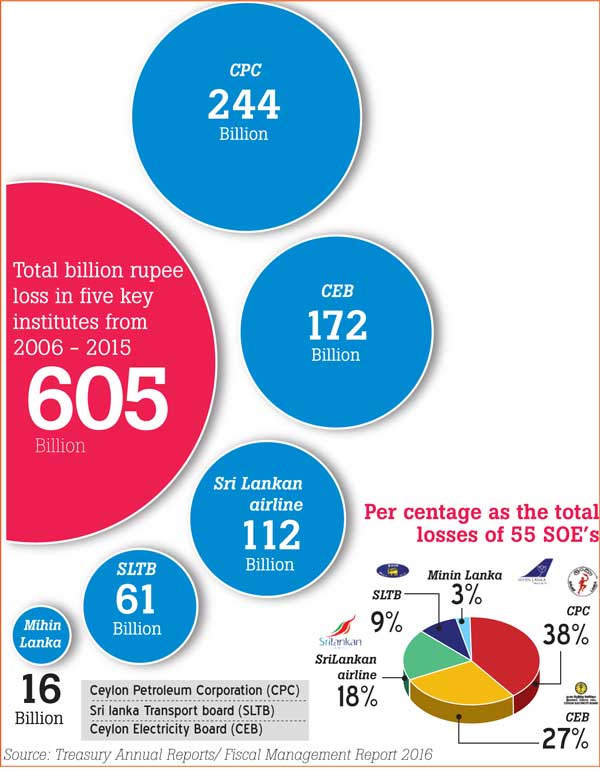

The total losses of the 55 SOE’s from 2006-2015 amounts to a gigantic Rs. 636 billion. Interestingly 5 key institutes are responsible for 95 percent of the losses which adds up to Rs. 605 billion losses. Namely Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lankan Air Lines, Mihin Lanka and Sri Lanka Transportation Board are the money eating machines of poor taxpayers.

Surprisingly significant discrepancies were identified even in the figures disclosed to public through the COPE report, the Treasury Annual Report and Fiscal Management Report for the same institute.

Obviously all 3 the figures cannot be true and we can come to a reasonable conclusion that either two figures or all 3 figures are false. The simple reason we cannot ignore the discrepancy is because it exceeds Rs. 5 billion of tax payer’s money. If I take examples of other institutes this column will run out of space

Naturally, with such drastic discrepancies the following appalling questions cross our minds: nAre accepted accounting standards followed when profit calculations are made? nIs the data fabricated to misguide the 20 million population?

Has COPE done their job well and does the money spent on the COPE committee justify taxpayer’s money.

If these government workers cannot manage these institutes and cannot even calculate profit and loss accurately, are they worth the money they are paid from tax payers’money. The ‘Profits and losses’ analysis shows that in 2011 and 2012 there is a sharp increase in losses and the reasons for the increase in losses should be investigated to avoid reoccurrence of such situations in the future.

Although it is a fact that the global economic conditions took a beating in 2012, but Sri Lanka had just emerged from a war situation in 2009, and this was a huge advantage to the Sri Lankan economy. SLTB and Mihin Air has failed to make any profit for last 10 long years and if a company cannot be turned around in 10 years, the ability of the management should be questioned. How many years must one wait to see a progress being made?

Sometimes we the ordinary citizens of Sri Lanka cannot comprehend the value of Rs. 605 billion. Most of us, including the ministers and parliamentarians confuse millions and billions. In order to illustrate the potential of Rs. 605 billion, a list of things which could be done, if the 5 key institutes were well managed and were able to break even is given below:

1. Ten more highways

The cost of southern high way was 60 Billion rupees and we could have easily built 10 southern highways connecting all corners of the island with this money because the cost of the southern highway was way above the average cost. The Ministry of Highways attributes the high cost to the high prices paid for land acquisitions and land diversity. Even if this is true, 10 highways with similar capacity could have been constructed for the same price.

2. Eleven harbours

The Hambantota port cost US$ 361 million and we could have built 11 ports and even saved another 600 million for the grand opening ceremony

3. Cover 81% of the current budget deficit

The current budget deficit is estimated to be LKR 740 billion rupees and if the 5 institutes mentioned herein could have performed at breakeven level, we could easily cover 81% of the current budget deficit

4. Twenty more airports

The current government is planning to make Sri Lanka an aviation hub and if they think they need airports like Mattala, even if it is only to store paddy during the harvest season, 20 similar airports could be built. The San Francisco Air Port in the USA, which incidentally is one of the top airports in the world, with the size of the runway being 3600 meters long and 45 meters wide is smaller than the Mattala airport runway which has a 3500 long and 60 meters wide runway. So I am talking about an investment of 20 airports having a capacity equal to the San Francisco Airport, not small domestic airports carrying light aircrafts

5. Nine power plants as Norochchole

Making a Sri Lanka a hub of energy is another popular topic in town. The first phase of Norchchole cost US$ 455 million and losses made by the 5 key SOE’s in 10 years is 9 times this cost.

6. 10% of the Megapolis project 2030

The initial mega project in 2016 targeting to make Sri Lanka a middle income country by 2030, requires an investment of US$ 44 billion. The Government could easily cover 10 percent of the total investment with the losses made by these key 5 institutes.

7. Relief of 22% of total tax revenue in 2016 on tax payers

The total estimated tax revenue of the government for 2016 is Rs. 1,584 billion. Even if Sri Lankan Airlines and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation could operate at breakeven level it could still cover 22 percent of the total estimated tax revenue from 2016 budget. I reiterate the values are just face values and the net present value (NPV) will show a worse situation

8. Rs. 30,000 bonus by the first citizen with his annual greeting SMS

Leaving alone all of the above, the President instead of sending a SMS message to all Sri Lankan citizens who own a phone, wishing them a happy Sinhala and Tamil New Year, could give a cash gift of Rs.30,000 to every citizen of this country, including newly born infants, if these 5 key loss making institutes performed better by breaking even. (Rs. 120,000 for a 4 member house family) With the losses incurred by Sri Lankan Airlines alone, the President could gift Rs. 5000 to each citizen.

What would be the solution?

It is a globally accepted theory that when you run a business, focussing on your strengths is a must and establishing monitoring and evaluation procedures is essential. If you do not possess the required skills or expertise within your organizations, you have to either hire the right people or outsource the job.I t is sad that the words like “Privatization” are injected as terrorist words into the blood of the nation but the reality is just leaving these 5 institutes in the hands of honest politicians had lost the country 605 billion which no one can justify. Those who promote concepts like state ownerships and big government has absolutely no idea on financial management.

If they had any sense on fiscal management a decade is a too long period even for a below average management. The fear of privatization is same as fear of failure and the success is always lies beyond our comfortable zone. It is Albert Einstein, the brain of the 21stcentury, who said “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”.

Dhananath Fernando is the Chief Operating Officer of AdvocataInstitute; an independent Sri Lankan think tank works for economic freedom. He could be reached via dhananath@advovata.org