In an extraordinary gazette notification released earlier this week, the Sri Lanka Consumer Affairs Authority (CAA) imposed price controls on bottled water, to be enforced starting today (Oct 5).

Advocata notes that this decision will introduce distortion into the market possibly resulting in lower quality or shortages. As more than 120 companies battle for a foothold in Sri Lanka’s competitive bottled drinking water market, worries over unsafe and low quality products is concerning.

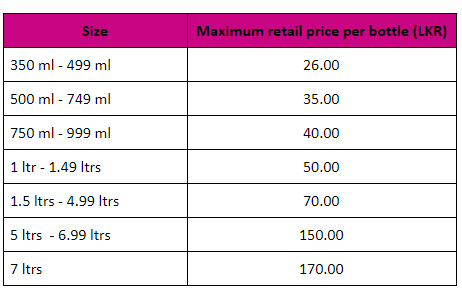

The maximum retail prices enforced through this gazette are as follows:

In principle, the action of setting maximum prices on goods and services is known as a “Price Ceiling”. These are meant to “protect” consumers from being exploited. Yet the reality may be different. A publication slated to release next week by Advocata, “Price Controls in Sri Lanka; Political Theatre” reveal that for the items surveyed price controls do not serve the intended purpose. Coupled with loose enforcement, consumer price controls in Sri Lanka have skewed the market towards a preference for lower quality products. The Price controls on water bottles, will likely to do the same.

According to a basic survey carried out by Advocata, market prices of bottled water for a 500 ml bottle, prior to the enforcement of the price control was as follows:

The bottled water industry has 120+ entrants in the market. This means that until today, consumers had the choice of purchasing a 500ml water bottle at Rs. 45, Rs. 50 or at Rs. 80. Consumers were given the choice to buy bottled water as per their personal preferences and budgetary constraints. This is no longer the case.

In Sri Lanka, bottled water is regulated by the Ministry of Health through the Food (Bottled or Packaged Water) Regulations, 2005 framed under the Food Act No. 26 of 1980. There had not been major health and quality related concerns until 2016, where a CAA directive indicated that plastic mineral water bottling standards were enforced starting September 1, 2016 following the authority detecting several brands using low quality plastic bottles.

The likely result of the introduction of this new price control -- limiting the sale of a 500ml water bottle to Rs.35 -- is that producers have to now cut down on production costs, to reduce the final cost per bottle. Low production cost lead to the sourcing of low quality raw materials, in this case; water and plastic. It also unclear whether the price controls also apply to glass bottles, which may be priced out of the market.

“In responding to price controls, the usual case is that producers would resort to producing low quality products in order to remain within the vicinity of the controlled price” says Ravi Ratnasabapathy, Resident Advocata Fellow and co-author of “Price Controls in Sri Lanka” report.

Advocata urges the government to engage relevant stakeholders and reverse the decision to unnecessarily intervene in an already competitive market.