In this weekly column on The Sunday Morning Business titled “The Coordination Problem”, the scholars and fellows associated with Advocata attempt to explore issues around economics, public policy, the institutions that govern them and their impact on our lives and society.

Originally appeared on The Morning

By Dhananath Fernando

This has not been an easy time. We are moving through the third week of Covid-19 in Sri Lanka following the identification of the first local patient. Medical experts have advised us to continue social distancing in the critical weeks to come. Fortunately, no deaths have been reported so far and a few patients have successfully recovered as of 27 March 2020. That’s a big relief. I am sure no Sri Lankan ever thought that one virus could have caused such damage, but it has.

According to the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA), we are in the third phase of the crisis. The Government and healthcare experts are doing a commendable job of putting a stop to the spread of the virus. This covers the healthcare side of the matter. The other side of the coin is the economic management that must complement healthcare measures.

As we are still in the eye of the storm, the short-term consideration of having enough essentials to put food on the table has been the focus. Before the spread of Covid-19, the Government announced a new direction on delaying debt collection and tax collection across different economic sectors for state and commercial banks, which included providing a moratorium for settling personal loans and vehicle leasing instalments. At the same time, the Central Bank directed banks to halt the provision of facilities to import vehicles and non-essential goods amid the value of the Sri Lankan rupee falling to a record low. On Thursday (26), the President requested that international agencies restructure debt repayments for countries that are most vulnerable, like Sri Lanka.

The Government’s relief package and the measures needed should be assessed based on the cost that the crisis cause our economy.

Measuring economic impact

In my opinion, when measuring the economic impact on our economy, we can zoom in on four sections. Since we are still riding out the storm, it will be too early to make an accurate estimate of the impact, but we can keep tabs on the matter. I have considered only variables that are measurable, leaving aside the cost of human lives; nothing is more valuable than the life of a fellow human being.

The cost associated with battling disease

For an $ 88 billion economy, and a country with a high debt-to-GDP ratio, the unexpected cost of healthcare and pandemic management falling in a critical year for debt settlements can have severe consequences. The setting up of quarantine facilities, attempts at expanding hospitals to battle Covid-19, and concessionary packages that have been provided for the most vulnerable segments in society are the main cost centres that fall within this category.

The cost due to loss of productivity and economic activity

Not every person can work from home, and the loss of productivity in agriculture, industry, and services will cost Sri Lanka as significantly as other economies. Our low economic growth amidst the tax cuts that were provided earlier this quarter further highlight the seriousness of this matter.

The loss due to the barriers on economic integration

The costs incurred by industries and the economy due to the disruption of economic integration are the final section that should be considered. Consumption will be very low in key European markets and in the US (our main export markets that contribute to about 35% of our total exports), which will affect demand. On the supply side, the time taken to replenish supply chains from China and other countries, especially for the apparel sector, will further impact our economy, as well as the rest of the world.

Import controls are not advisable

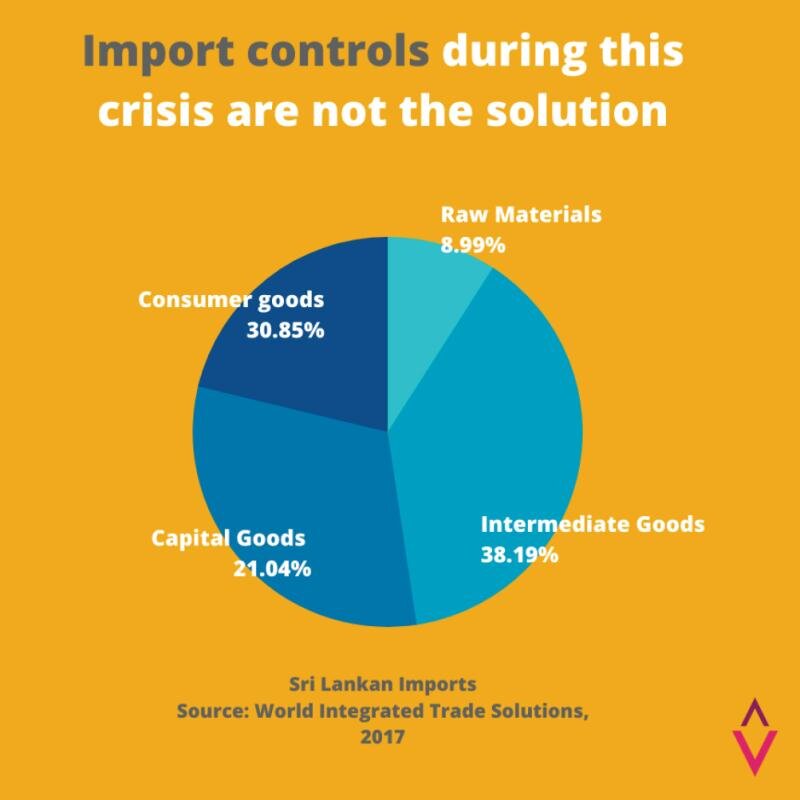

Many governments across the world announced stimulus packages for their economies. In Sri Lanka, the Central Bank gave directions to halt the importation of non-essential goods. This was taken as a measure to defend our currency and to bring our import bill down, but there is very little empirical evidence supporting the defence of a currency through import controls. In the Sri Lankan import basket, about 9% accounts for raw materials, another 38% for intermediate goods, and about 21% for capital goods. Petroleum is the main import, followed by raw materials for the apparel industry. Pharmaceuticals are included amongst the 30% of consumer goods imported.

Imposing import controls in the first place in defending the currency gives a wrong signal to industries and investments at a time when we need them the most. Similar measures taken by the previous Government and other governments in the past ended with the rapid deterioration of the currency and, ironically, the reserves that were used to defend the soft peg. We have to back our currency with precious metal such as gold (gold standard) or a stable currency, which is called the hard peg (a fixed rate, normally with a hard currency like the US dollar), which can be managed by a currency board (we currently run a soft peg where money can be printed without being backed by hard currency). Most developing countries shun currency boards as it imposes monetary and ultimately fiscal discipline. In the meantime, it is indicated that the Central Bank has printed about Rs. 100 billion between 13-24 March 2020 and this will be the main reason for the currency to fall further.

Secondly, an essential good for one person may be a non-essential good for another person, and vice versa. For example, a can of tinned fish may be essential for one household but for a vegetarian household, it would not even be considered an option. Many similar cases arise when governments try to intervene in defining essentials and non-essentials.

Difficulties in targeting the informal sector

In the Government’s stimulus package, a systematic targeting concern arises regarding the informal sector in the economy. Most businesses operating in Sri Lanka fall within the micro, small, and medium sector, and a considerable amount are not registered. The Government will not be able to capture these under any stimulus package, so we have to be prepared for the impact it will have on our economy. Small-time tailors, barbers, car mechanics, fruit and vegetable sellers, furniture shops, and many businesses operate within this informal sector. They do not operate within the system of formal bank facilities through commercial banks or non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs). Instead, many work with loan sharks with loans having interest rates of 10-12% per month with an efficient collection system and a 100-day repayment period with interest and capital. For example, if I take a loan of Rs. 100,000 with a 90-day repayment period at 10% monthly interest, there will be a collection representative every day in the evening at my doorstep and I have to pay 1,500 daily (1500*90 = 135,000). In Moratuwa, where I live, where the furniture business is the main industry, I can just walk in with a cash cheque dated for three months and even get a couple of millions in less than 15 minutes. There are separate cheque collection shops in my area. Therefore, the Government will face the challenge of targeting this stimulus package to minimise the cost of loss of productivity, particularly in the informal sector.

In summary, there is an “announcement effect” and a confidence effect created by the relief package announced by the Government among the people who are not a part of the informal economy, but policymakers should take note that there are also vulnerable sectors that shoulder a large portion of our economy which has an impact on our daily life.