Originally appeared on The Daily FT

By Dr. Sujata Gamage

With the sudden closure of schools on 12 March, the Sri Lankan education system plunged into a crisis. Overnight teachers had to gear themselves for on-line teaching and other methods of distance education. In contrast to higher education, distance education for school-age children is a new phenomenon.

The Government of Sri Lanka swiftly moved in to address the concerns of students preparing for Grade 5 Scholarship examination and Ordinary Level and Advanced level examinations, due to start from August, by telecasting lessons for those students. However, the schools were not at all prepared for a distance learning mode, and hence innovation became an urgent necessity to reach out to the full student population.

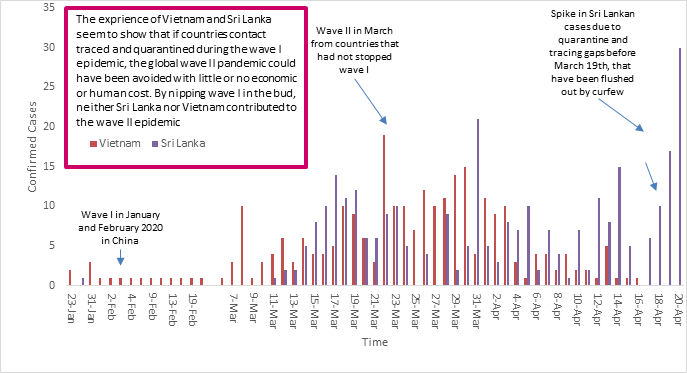

Further, COVID-19 is not going to be fully curtailed anytime soon. Even if schools start, we can expect sporadic disruptions due to new waves of the pandemic. Therefore, it is critical that we come up with short-term fixes as well as long-term solutions to the distance education of school children in the time of calamities.

Considering the need, the Education Forum Sri Lanka (EFSL) has initiated a series of virtual dialogues on ‘Distance Education in the time of Calamities and Beyond’ to identify good practices in distance education and make recommendations to policymakers. Twenty or more case studies gathered through a focus group of teachers and researchers and further contributions by the participants of our first dialogue revealed several issues.

More than 60% of households with school-age children have no internet

According to a comprehensive survey of mobile use in Sri Lanka by LIRNEasia, in 2018 only 34% of households in Sri Lanka with children aged five to 18 had an Internet connection. More than 90% of these connections are accessed through mobile networks using a smartphone.

Of these households with internet access, an Online Realtime Classroom experience is enjoyed only by students attending a few select schools. This experience would be for about one to two hours per day, with a variety of self-learning educational materials supplementing the online experience. The percentage of children receiving such an online classroom experience seems negligible given that even some of the popular schools in Colombo have not been able to provide that kind of experience to their students.

Essentially, the primary mode of distance education for 34% of families with internet access is receiving notes or assignments over mobile apps like WhatsApp and Viber. For those families for whom the smartphone is the only device connected to the Internet, dedicating it to the use by one or more children, with or without adult supervision, is difficult. When large quantities of notes are sent, the situation becomes unmanageable. The other 60% remained unreached.

Notes and tutes sent over WhatsApp is not education

Parents cannot substitute for teachers. Even parents who are teachers find it difficult to teach your own child at home. Without adult guidance, notes and tutes do not make an education. Further, as parents are finding out, the problem is not technology.

The mode of education in Sri Lanka, where large quantities of facts are communicated to children in preparation for exams, is perhaps the biggest barrier to distance education. Students being used to spoon-feeding is also tied to this testing of facts through examinations.

Plan around the least privileged

The situation is not dire. Even those unconnected are not without resources. To quote Kagnarith Chea, a young social entrepreneur from Cambodia with whom I communicated recently:

“Distance education requires one of three things – Device (phone, tablet, computer, TV), Network (intranet or internet) and Content. In an ideal situation, all three should be available. In a no-choice situation where there is no internet, we can do without it. In fact, when we launched my educational programs through Edemy we did it without the internet. So long as there are devices and content, distance education is still possible. I believe that this is the best scenario for kids without access to the internet in the time of COVID-19. There are always limitations, but access with limitations is better than not having access at all.”

In Sri Lanka, textbooks are given free of charge for all subjects in Grade 6-11, making notes and tutes sent over WhatsApp somewhat redundant. Mail service is available for almost all homes. In a partial lockdown, VIP services can be arranged for school children. Broadcast TV and radio are other modes that are more widely available. As some tech experts have pointed out memory cards or micro-SD cards have a lot of potential for distributing content under no internet conditions. These limitations have their positive side too.

Benefits of a leaner and smarter education will accrue to all

Thinking of distance education under low resource conditions of the least privileged forces us to focus on parts of the curriculum which can be integrated and parts which need to be taught on their own, and ration content overall. If the content is less and students are guided to be self-directed, some of these non-internet solutions can in fact lead to a quality distance education.

Although the lockdown may be eased, schools may not start for some time, and the necessity of communicating a leaner and smarter education to children without internet may benefit the education of all children irrespective of their level of access to technology.

No-internet scenario with rationalised content

For example, if we decide that Math is a subject where children will suffer most if they get less schooling, the full focus during a pandemic-induced distance education can be on that subject while other subjects are integrated into a lesson plan where key concepts are threaded around one or more themes.

For example, valuable contact time and content delivery mechanisms can be focused on teaching math. Since students already have textbooks, all additional content will be supplementary, providing entertaining ways for children to learn difficult to grasp concepts.

DVDs could be prepared and provided ahead of time for families to play over their TVs. Micro-SD cards can be made available for each math lesson for each grade. Owning a smartphone to use supplementary learning materials is more likely than parents purchasing internet access for undefined content.

Once school starts, home-based learning drills could include sessions where students try to learn on their own using supplementary materials while the teacher plays the role of a parent who is more involved in the logistical aspects.

Now, how would one integrate other subjects around one or more themes in distance learning situations? For example, for Grade 16-9 there are 13 required subjects. If you take mathematics out, COVID-19 epidemic provided the best theme ever for bringing other subjects – language, science, history, geography, religion, aesthetics, citizenship, health and physical education practical and technological skills and IT subjects together. The average teacher would need help with theme-based teaching and teacher associations led by veteran teachers could lead the way by developing and sharing lesson plans.

Overnight, we could go where Finland has reached after years of providing world-class education in a traditional mode. Finland recently announced they will not divide school time into subjects anymore and students will learn key concepts of several subjects woven together around selected themes. If in Sri Lanka we are forced by necessity to limit content through the integration of subjects around a theme, when our children return to school, they may want such education to continue.

But internet access for all should not be far away

Sri Lanka and most developing countries have come a long way from a situation where owning a phone was a luxury to where, for example in Sri Lanka, 97% of households have access to a mobile phone. However, access to the internet is available for less than 50% of households in Sri Lanka.

If parents see the benefits of their children learning to learn using supplementary content and note that children with better access to the internet have more and better content, those parents will go the extra mile to secure internet access for their children.

According to the 2016 Household Income and Expenditure Survey of Sri Lanka, parents in Sri Lanka already spend 50% of their education expenditure on tuition. If the need for tuition is reduced through a fewer number of examinations to be faced by children and students are required to learn on their own supplementing textbooks with e-content, it could well be that education will be the driver of digitalisation of Sri Lanka.

The opinions expressed are the author’s own views. They may not necessarily reflect the views of the Advocata Institute or anyone affiliated with the institute.